WOC 177

Page 177

Other Forms of Explanatory Writing

Imagine that you were stranded on an asteroid. What would you do? If you had Internet access, you could message or email for help. You might also learn how to order a ride with Space Uber or Lyft Off. Or you might learn how to build a do-it-yourself spaceship. Writing that explains how to do something helps us accomplish great things.

Explanatory writing also does other jobs. It might compare and contrast two subjects (Space Uber versus Lyft Off). It might instead show causes and effects (why rocket fuel oxidizes). This chapter shows how to write these special forms, and how to create an effective response to an explanatory prompt on a test.

What’s Ahead

WOC 178

Page 178

How-To Essay

A how-to essay describes a process. This type of essay is organized chronologically (first, next, then . . . ). How-to essays tend to use command sentences, telling the reader what to do at each step. In the following essay, Rodrigo tells how to jump-start a car.

How to Jump-Start a Car

Beginning:

The beginning introduces the topic and states the thesis (underlined). Last Saturday, the starter on Mom’s SUV just went “click, click, click.” Mom said, “It’s time you learned how to jump a car.” Jump-starting a dead battery is easy and safe, if you do it the right way.

Middle:

The middle paragraphs explain the equipment and the steps. First, gather your equipment. You need jumper cables, which are thick, insulated wires with black and red clips at either end. You also need a car with a good battery.

Start by prepping the cars. Pull the car with the good battery close to the other car. Make sure both cars are off and in park or neutral with the parking brake on. Lift the hoods and find the batteries, which are rectangular boxes with terminals on top. The positive terminal has a plus or “POS,” and the negative has a minus or “NEG.”

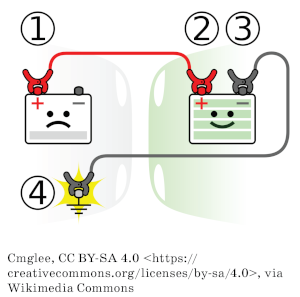

An illustration clarifies the process and cites the source. Next, you need to attach the jumper cables. Clip one end of the red jumper cable to the positive terminal of the dead battery. Attach the other end to the positive terminal of the good battery. Then attach one end of the black jumper cable to the negative terminal of the good battery. Attach the other end to an unpainted piece of metal on the car with the bad battery. This grounds the cables to prevent sparks.

Start the car with the good battery and let it run. Its battery is now charging the dead battery. After five minutes, try to start the car with the dead battery. If it doesn’t start, give it five more minutes. When it starts, leave both cars running. Remove the clips in the opposite order that you put them on.

Ending:

The ending wraps up the how-to essay. Shut off the car with the good battery and drive the other one for 20 minutes so its alternator can fully charge the battery. Then you might have a mechanic see if you need a new battery.

WOC 179

Page 179

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Selecting a Topic and Gathering Details

Think of things you know how to do well—or things you would like to learn how to do. Select a topic that you can cover in an essay. Then list all the tools, equipment, or supplies that you need. Make a separate list of the steps to take. Conduct research to fill in any gaps.

Focusing Your Essay

Write a thesis statement that names your topic and encourages your reader to try the process:

Writing ■ Connecting Your Ideas

As you write your first draft, imagine explaining the equipment and the steps of the process to a friend. Think of what the person knows and needs to know. Use command sentences and sound encouraging.

Revising ■ Improving Your How-To Essay

Use this checklist to revise your essay.

_____ Do I explain an interesting process and include the correct steps in the correct order?

_____ Does my beginning introduce the topic and state my thesis?

_____ Do the steps in the middle appear in time order?

_____ Do I use command sentences and define important terms?

_____ Does my ending effectively wrap up my writing?

Editing ■ and Proofreading ■ Checking Conventions

Use this checklist to polish your essay.

_____ Have I checked end punctuation and commas?

_____ Have I correctly capitalized first words and proper nouns?

_____ Have I checked spelling and easily confused words?

WOC 180

Page 180

Comparison-Contrast Essay

In this comparison-contrast essay, student writer Joan Becker writes a point-by-point comparison of butterflies and moths.

Figuring Out Flutterers

Beginning:

The beginning introduces the topic and states the thesis (underlined). Butterflies flutter through the world by day, and moths flutter through by night. Both are part of the lepidoptera order of insects with scales on their wings. Scientists tell them apart by, of all things, their antennae (“Moth”). Butterflies and moths have many similarities but also quite a few surprising differences.

Middle:

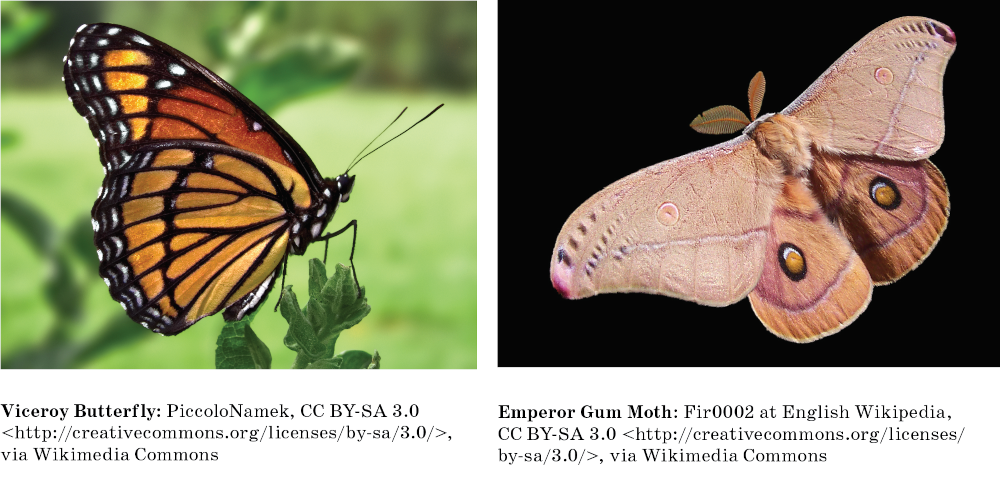

The first middle paragraph compares appearance, with photos and credits. The first main differences relate to body shape and appearance. As indicated, butterflies usually have clubbed antennae, while moths usually have feathery antennae. Butterflies have four wings, which they hold straight up at rest, while moths rest with their four wings held flat over the surface where they sit. As diurnal (daytime) creatures, butterflies often are brightly colored, which can signal poison or bad taste to predators. As nocturnal (nighttime) creatures, moths are often dull colored or camouflaged. Butterflies tend to have long, thin bodies, and moths stout, furry bodies (Hauser).

The second middle paragraph focuses on life cycles. Both insects go through metamorphosis, but with slightly different steps. Butterflies and moths both begin as eggs, hatch into caterpillars (larvae), and pupate into winged insects. However, butterfly pupae transform as a hard-shelled chrysalis, while moth caterpillars spin silken cocoons around themselves to undergo their transformations (“Life”).

The next paragraphs address origins, diets, and economic value. Moths have many more species and are much older than their cousin fliers. Moth fossils date back 190 million years, while butterflies broke away from their moth ancestors about 100 million years ago. As a result, there are 160,000 species of moth, some that have never been studied, but there are only 18,000 species of butterfly (Hauser).

Moths and butterflies have similar diets. In their caterpillar forms, they tend to feed on plants, which can make them a nuisance by destroying crops. In their full adult phase, they feed on nectar, thus pollinating plants. Some moths pollinate plants that bees largely ignore, making them critical to ecosystems. Some moths also like to eat clothing made of wool or cotton, which is why people line closets with aromatic cedar or use mothballs to keep out the pests.

Both insects have tremendous economic value as pollinators, but moths have other contributions. In Africa, moth caterpillars provide an important source of protein. In China since ancient times, farmers have raised silkworms (caterpillars of the moth Bombyx mori), whose cocoons are made of silk. Every year, these little worms produce $250 million worth of silk (“Moth”).

Ending:

The ending leaves readers with a thought that sums up the ideas. Aside from economic benefits, a Monarch butterfly fluttering from flower to flower brightens any picnic. And the white jitter of moths haunt our porch lights. These cousin insects are important and beautiful creatures, pollinating day and night.

Note: The works-cited page is not shown.

WOC 182

Page 182

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

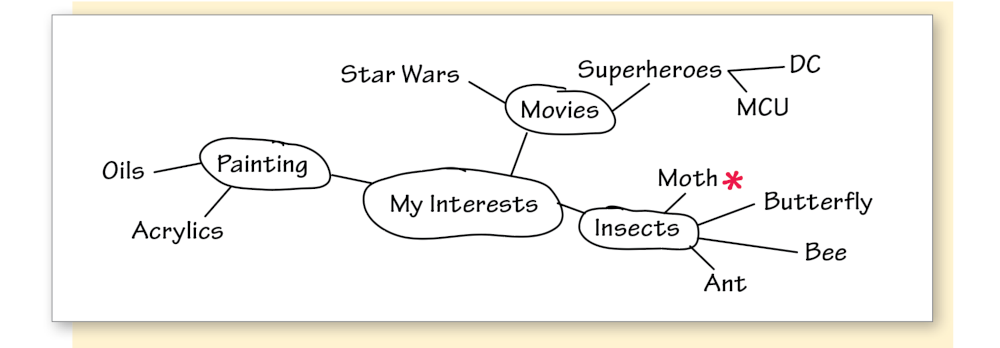

You will need to select two related topics for your comparison-contrast essay. Joan wanted to write about something that really interested her, so she brainstormed ideas using a cluster. “My Interests” is the nucleus of her cluster.

Clustering

Joan's cluster generated more than one possible writing idea, but she decided to compare butterflies and moths.

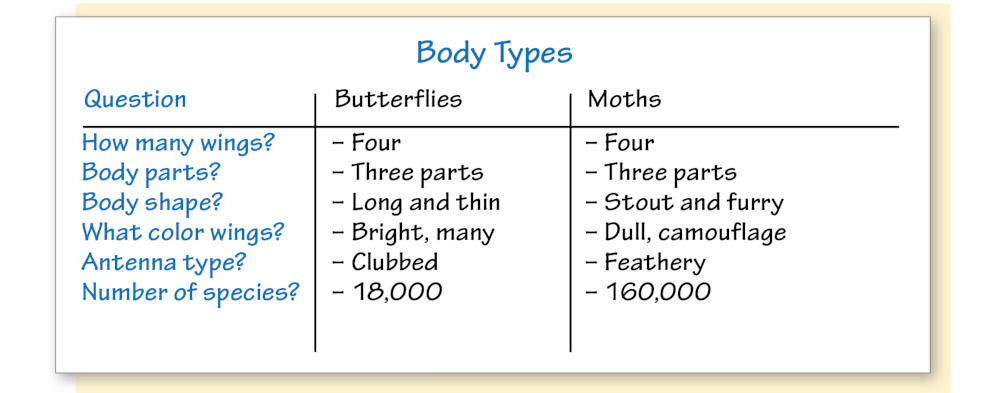

Gathering Details

You will next need to collect and organize details about each topic. Joan collected details from websites, books, and magazines; and she used a gathering grid to track her research.

Gathering Grid (first part)

WOC 183

Page 183

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

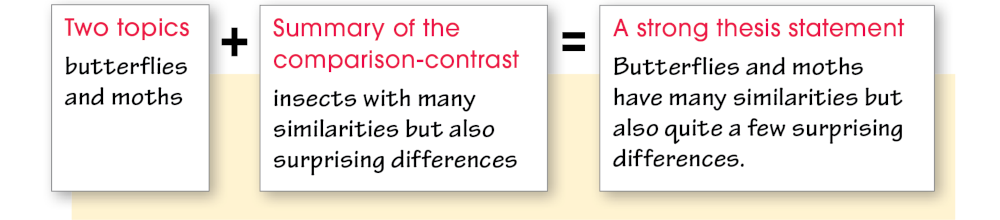

Beginning ■ The beginning should introduce the two topics in an interesting way and lead up to the thesis statement. Joan began her first draft by introducing some differences between butterflies and moths. Next, she used the formula below to write her thesis statement.

Thesis Statement Formula

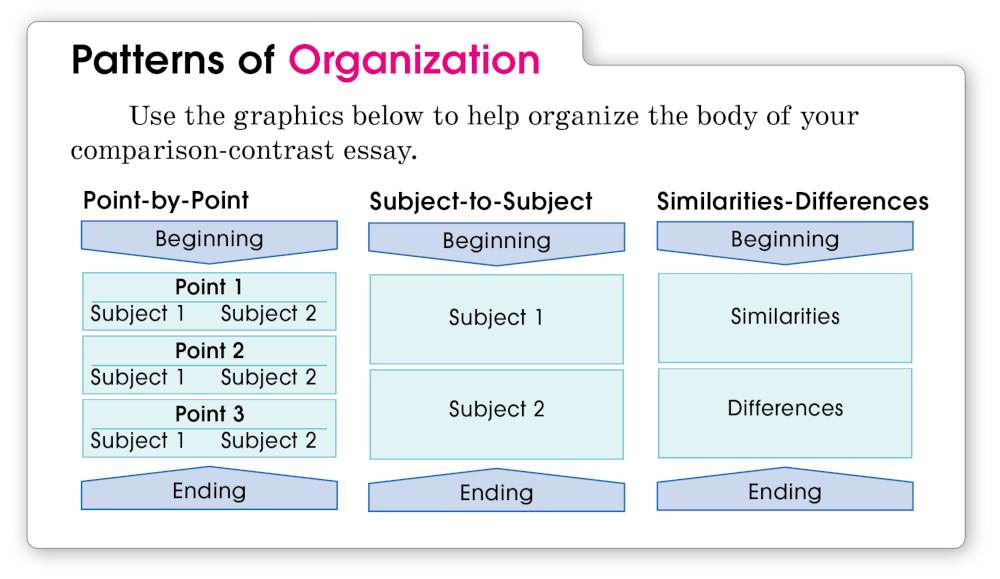

Middle ■ After forming your thesis statement, you should write the middle part of your essay following one of the comparison-contrast organization patterns. Joan used the point-by-point organization pattern. Each middle paragraph focused on a different point of comparison between butterflies and moths.

Ending ■ Your ending should leave the reader with something to remember about the topic. You can emphasize a key point, share one more insight, or refer back to the beginning. Joan left the reader with a strong final thought.

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving the Writing

During the revising process, consider, among other things, the organization of your writing. (See page 188 for a complete checklist.)

_____ Does the essay follow one of the comparison-contrast organization patterns?

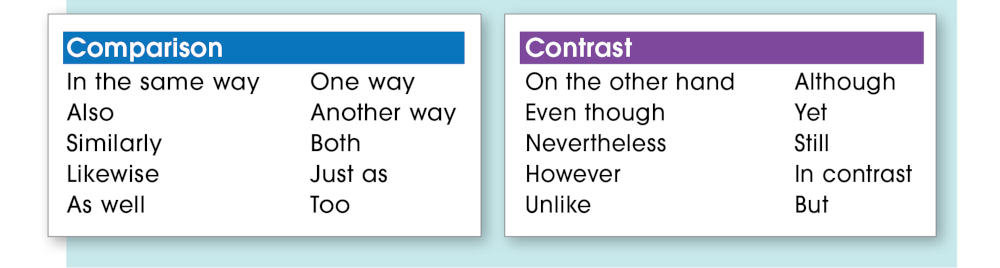

_____ Do I use appropriate transitions? (See below.)

WOC 184

Page 184

Cause-Effect Essay

In this cause-effect essay, Jamaine Reilly writes about the cause of gravity and its many effects.

What Causes Gravity?

Beginning:

The beginning introduces the topic and states the thesis (underlined). The story goes that Sir Isaac Newton was sitting under a tree when an apple fell on his head. He wondered why, and his answer was “gravity.” Newton then came up with an equation for the force of gravity, but he still didn’t understand how this force could work at a distance. How did the Earth know the apple was there? Einstein helped us understand the cause of gravity, and knowing the cause helps us understand its many effects.

Middle:

The first middle paragraph explains the cause of gravity, with a public domain image. Einstein explained gravity by saying that space and time form a stretchy fabric, which he named “spacetime.” Gravity is actually a curvature of spacetime. A massive object like Earth creates a “gravity well” in spacetime so that other objects passing by curve toward it. These objects are actually following straight paths in curved spacetime (Neilson).

The next middle paragraphs focus on the effects. Gravity is by far the weakest of the four basic forces. The nuclear strong force, the electromagnetic force, and the nuclear weak force are at least 1025 times more powerful, but they have a very small range. Gravity, on the other hand, has an infinite range. That means that gravity is unimportant at the quantum level of atoms, but it rules the macro level of the universe MLA citations credit sources. (Neilson).

In fact, gravity has formed all of the stars and planets and galaxies. It causes matter to clump together. Gravity makes a cold cloud of interstellar gas condense and clump into a protostar. When enough matter packs together, gravity creates such intense pressure and temperature that fusion reactions begin. Hydrogen atoms fuse into helium atoms, and a star is born. At the same time, all around the newborn star, a disk of gas and dust gets pulled together by gravity into protoplanets (“Gravity”).

The writer shows how gravity shapes our planet. Gravity built the Earth and continues to build it. It made the heaviest materials sink to the iron core and mantle, forcing the lighter continental plates up to float on top. Water weighs less than rock, and air is lighter than water, so gravity formed the oceans, lakes, and rivers as well as the atmosphere above it all. Gravity moves the continental plates against each other, shoving some down into ocean trenches and piling others up into mountains. Then it brings rain and snow to erode those mountains, carrying their sediments down to the valleys. In a universe that tends toward disorder (entropy), gravity sorts out the matter.

Living things rely on gravity, too. Plants struggle in a weightless environment because gravity tells them which way is up and which way is down. People on the International Space Station also struggle without gravity. In a weightless environment, their bones decalcify and their muscle atrophy. After a long stay, most astronauts can’t walk when they first return to Earth (“Weightless”).

Ending:

The ending reflects thoughtfully on the effects. So gravity does much more than make apples fall on the heads of scientists. It ignited our sun and keeps it burning. It dictated the structure of our planet and continues to shape it. It makes life possible for all the plants and animals that live here. Gravity even built the Milky Way, our local group of galaxies, and our whole universe.

Note: The works-cited page is not shown.

WOC 186

Page 186

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Keep the word change in mind as you begin thinking of cause-effect topics. Change is always caused by something, and every change, even a small one, can produce a number of effects. For your essay, consider changes that have affected people locally, nationally, or globally.

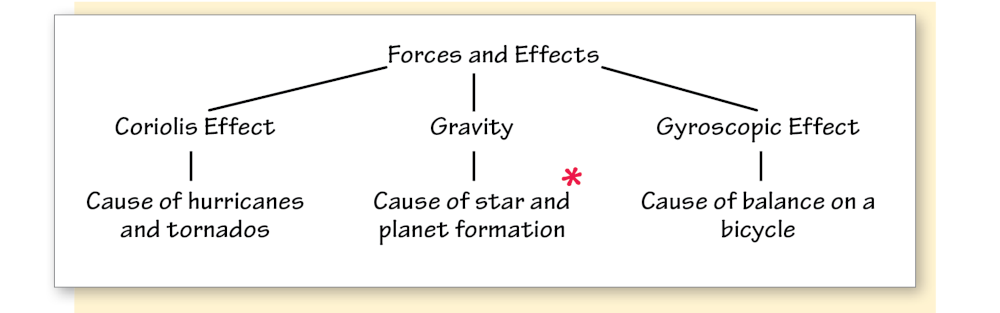

Jamaine started his topic search by thinking about topics he was studying in his physical science class. To narrow his focus, he made a topics chart with three categories. He starred the topic that interested him most.

Topics Chart

Gathering Details

To write an effective cause-effect essay, you will need to research your topic. Jamaine used his physical science textbook as well as website articles. You might need to interview people or attend events.

Jamaine used note cards to keep track of his research.

Note Card

WOC 187

Page 187

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

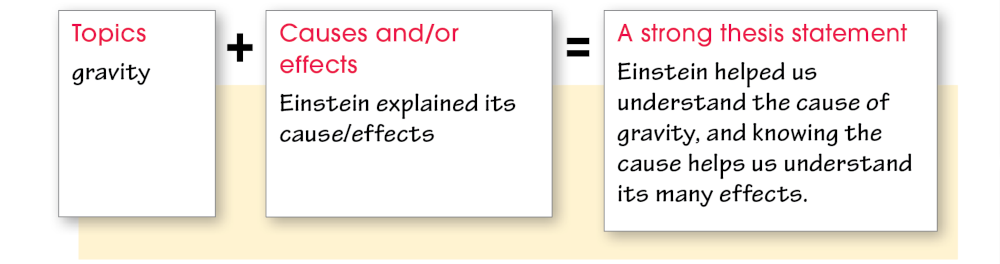

Beginning ■ In your first paragraph, capture the reader’s interest and state your thesis. Jamaine introduced his topic with an anecdote. He then wrote his thesis statement following the formula below. The thesis statement gave Jamaine a focus for the remainder of his essay.

Thesis Statement Formula

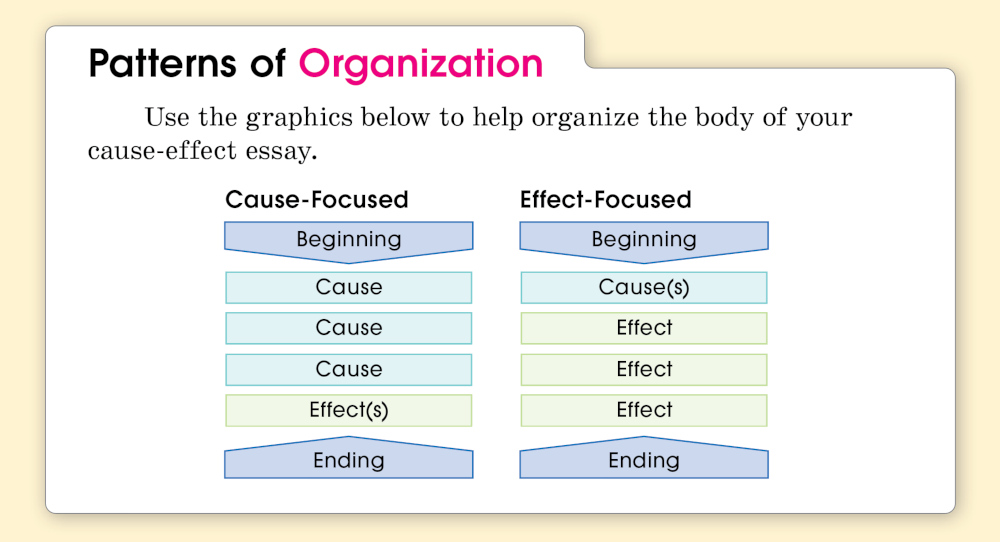

Middle ■ Select an appropriate pattern of organization for your essay. Then develop the middle part of your essay. Be sure to expand on the key ideas with specific details—facts, definitions, examples, and so on. In his first middle paragraph, Jamaine explained the cause of gravity and spent the other middle paragraphs discussing its effects.

Ending ■ The ending paragraph should tie all the information together and close with a memorable final sentence. Jamaine reviewed all of gravity’s effects, ending with its universal importance.

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving the Writing

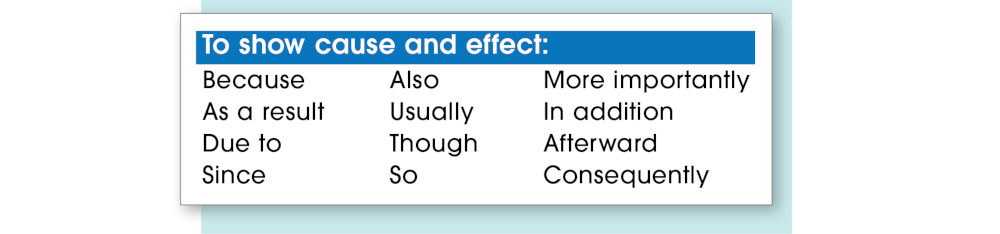

During the revising process, pay special attention to the organization of your essay. (Also refer to the checklist on the next page.)

_____ Does my essay follow one of the cause-effect organization patterns?

_____ Do I use appropriate transitions? (See below.)

WOC 188

Page 188

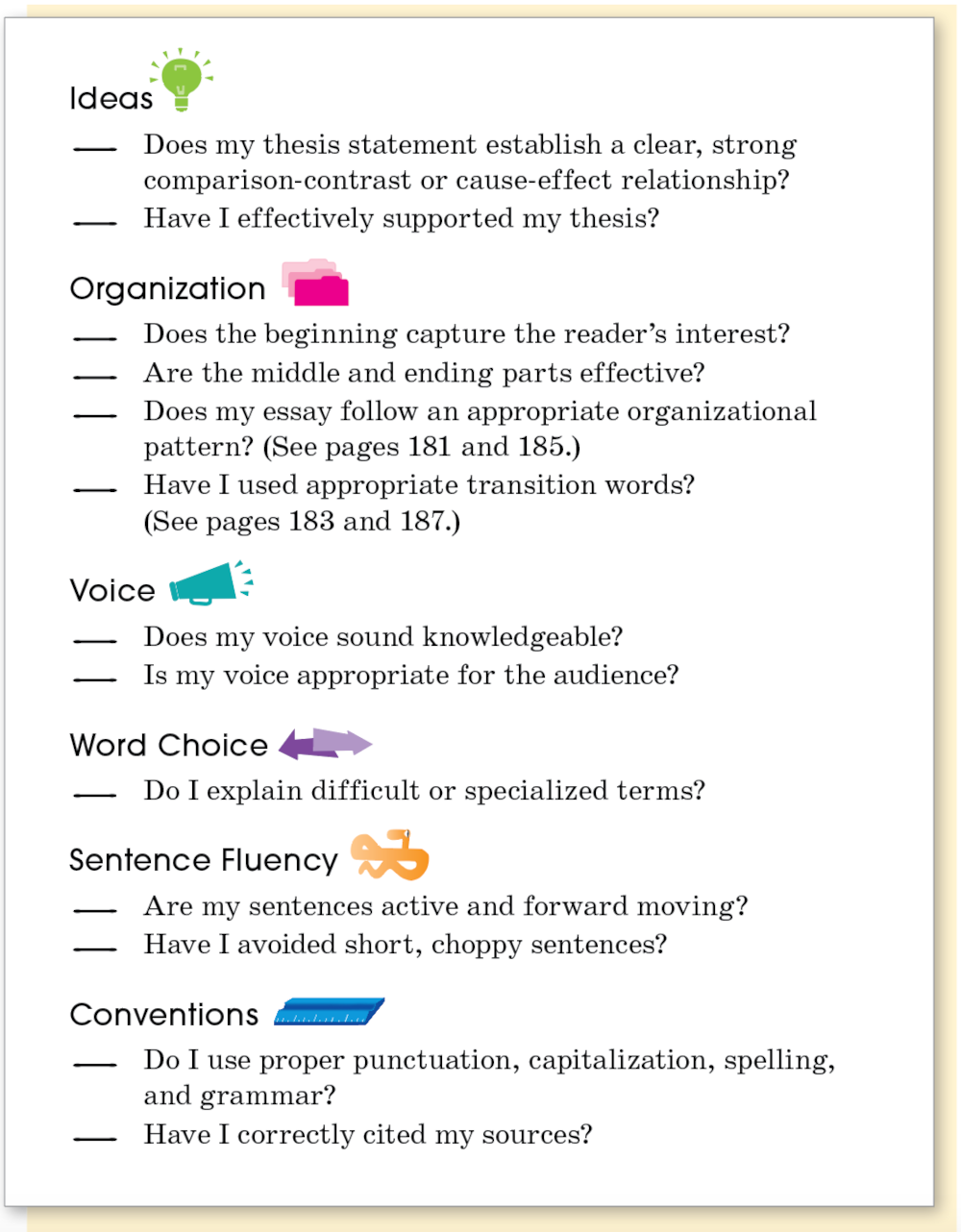

Revising and Editing Checklist

Use the checklist below as a guide when you revise and edit your two-part explanatory essays.

Two-Part Explanatory Essay Checklist

WOC 189

Page 189

Responding to an Explanatory Prompt

Prompt:

School teaches you a lot about math, science, history, and language, but it also teaches you about life. Think about the life lessons you have learned in middle school. Write an essay that explains to new middle school students three or four of the life lessons you have learned.

Prompt Analysis

■ Purpose: To explain

■ Audience: New middle school students

■ Subject: Life lessons learned in middle school

■ Type: Explanatory essay

Planning Quick List

Middle school life lessons

— Read the room.

— Connect.

— Get involved.

— Keep your board up

Response

Life Lessons from the Middle

Beginning:

The opening introduces the topic and states the focus. As you enter middle school, you have a lot to learn. How’s your plane and solid geometry? Can you tell a prepositional phrase from an infinitive phrase? Don’t worry. You’ll learn those things in middle school and more important stuff. I’ve learned four key life lessons while I’ve been in middle school.

Middle:

Each middle paragraph covers a separate main point. The first life lesson is to “read the room.” In elementary school, I had one main teacher and other teachers for art, gym, and music. In middle school, I suddenly had seven different teachers and a home room and an advisor. That’s nine different people, with different goals and class rules. A joke that would work in my English class would get me in trouble in math. Every time you land in a new room, learn the rules of the new game you are in. Then play to win.

Next in middle school, you need to connect. In class, the hallway, and the cafeteria, listen for people with similar interests. Share your interests, too. Watch for someone having a rough day, and help that person. Make friends with students, and connect also with teachers. You don’t need to go through middle school alone.

Transitions introduce the middle paragraphs. In fact, you should take connection one step further by getting involved. Go out for cross-country or join a choir. Learn how to play chess or how to shoot arrows at targets. If you join a club or team, you’ll meet other people with your interests, and you’ll have experiences together that will create friendships. Did you know that students who get involved actually do better in class? Being part of something bigger helps you feel like you belong in school.

Details support each main point. The last life lesson I’ll share actually came from a middle school club. I joined the Water Sports Club and learned how to wakeboard. I quickly found out that you have to lean onto your back foot and keep the front of your wakeboard up. That way, when the boat tows you, you stay on top of the water. If you let the front of your wakeboard down, it’ll catch on the water, and you’ll wipe out. That’s like life. You’ve got to lean back and keep a positive attitude. Then you can meet the biggest waves with a smile and fly over them. Don’t let your attitude drop too low, or you’ll take a header and go under.

Ending:

The closing paragraph summarizes the main points and offers a final idea. Beyond math, science, and social studies, middle school can teach you a lot about life. First, you’ve got to read the room, figuring out the rules of the game and how to succeed. Then you’ve got to connect to others and get involved so that you don’t have to go through everything alone. Finally, you need to lean back and keep your spirits up. Then you’ll be able to ride the waves of life like a champion.

WOC 191

Page 191

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Getting Ready to Write

Start by analyzing the prompt using the PAST strategy:

■ Purpose: Why am I writing? To explain? To compare?

■ Audience: Who will read my writing?

■ Subject: What topic should I write about?

■ Type: What form will my writing take?

Planning Your Writing

Choose a specific topic and decide how you want to write about it (your focus). Form a quick list identifying the facts, reasons, examples, or explanations you will use to support your focus.

Writing ■ Drafting Your Response

Beginning ■ The beginning of your response should introduce your topic and identify your focus. (“I’ve learned four key life lessons while I’ve been in middle school.”)

Middle ■ Explain the facts, examples, or reasons that support your focus. Refer to your quick list for guidance, but also realize that you will need to add details to develop each main point from your quick list.

Ending ■ Restate your focus, summarize your main points, and/or provide a final idea about your topic.

Revising ■ and Editing ■

Save 5–10 minutes to revise and edit your response to the prompt. (Download a checklist.)

_____ Ideas Have I clearly stated the focus of my explanation and supported it with enough details?

_____ Organization Is my response organized and easy to follow?

_____ Voice Do I sound honest and sincere?

_____ Word Choice Have I used the best words to develop my response?

_____ Sentences Are my sentences smooth reading?

_____ Conventions Is my writing free of careless errors?