WOC 387

Page 387

Reading Fiction

Human beings have always told stories, from the ancient epics of Greece to the modern manga of Japan. Stories entertain us and teach us and move us. They help us understand how life works and how people do, too.

In school you may read some challenging stories, novels, and plays—what tend to be called “literature.” Sometimes, they require you to slow down and pay special attention, but if you do, you’ll fall in love with these stories also.

This chapter teaches strategies you can use before, during, and after reading challenging literature. It also defines many of the key terms for analyzing fiction. Soon, you’ll not just know about characters, plots, settings, and point of view but use them to discuss fiction with friends. You might even write your own stories!

What’s Ahead

WOC 388

Page 388

Before Reading

Before you read a piece of fiction, you should preview the text. Previewing involves finding out about a novel or story so you know what to expect. You can learn something about a story by skimming the first few pages. You should also get a feel for the language the author uses: Will the story be easy or hard to follow?

Tips for Previewing

■ Consider the basic elements of fiction.

- Characters: Who are the main characters?

- Setting: Where and when does the story take place? What is the location like? What is the time period like?

- Conflict: What problem or event starts the action?

- Plot: How do the main characters respond to the conflict?

■ Think about other features.

- Narration: Who is telling the story? Is the story told about the main character (third-person point of view), or is it told by one of the characters (first-person point of view)?

- Language: What types of words and sentences does the author use? (This is the author’s style.) Are the ideas easy to follow? Is there a lot of description?

- Dialogue: Do the characters speak a lot or only a little? What do their words tell you about them?

- Type: How would you classify the selection? Is it historical, modern, or futuristic? Does the story seem serious, funny, or something in between?

Helpful Hint

Previewing a story is important if the story is challenging or complicated. Simple stories can be read with little or no previewing. You will need to decide.

WOC 389

Page 389

■ Preview the selection.

Short Stories: Because short stories are short, they do not offer clues like chapter titles or illustrations, but you can still preview them. Here’s how:

- Ask yourself what the title tells you about the story.

- Research the author on the Internet. Determine what types of stories the author usually writes. Find out other information, too, such as the author’s background and interests.

- Read the first few paragraphs. Look for details about the main character, setting, and conflict. Also consider the language: Is it easy or hard to follow?

Novels: Novels are a great deal longer and more involved than short stories, so there is much more to preview and learn.

- First, ask yourself what the title tells you about the novel.

- Then on the back cover and/or on the first few pages, look for a plot summary, a preface or introduction, and author information.

- If needed, refer to the Internet for additional information about the author.

- Review the chapter titles and any illustrations. Decide what they tell you about the plot line.

- Read the first page or two. Look for hints about the setting, the main characters, and the problem they face. Also consider the language: Is it easy or hard to follow?

During Reading

To gain the most from fiction, be an active reader. Active reading requires that you interact with the text, often through quick writing.

Tips for Reading

■ Think about the basic elements of fiction.

- Who are the main characters, and what are they like?

- What is the setting (time and place of the action)? How does the setting affect the story?

- What problems are the main characters facing? How do they deal with these problems?

- Who is telling the story (narrator)? What effect does the narrator have on the story?

WOC 390

Page 390

■ Read actively and record your thoughts.

- Predict upcoming events. Think about what may happen next in the story. This will keep you focused on your reading.

- Infer. Think about each character’s actions—what he or she does and thinks—to come to a deep understanding of the person. Ask yourself what you can learn from these actions.

- Check your understanding. At different points during your reading, stop and think about the story. Or better yet, explore your thoughts and feelings in writing. Consider what concerns or questions you have up to that point, how you feel about the character, and so on.

- Summarize. When you’re through reading for the day, write a brief summary of the unfolding story. (See pages 294–295.)

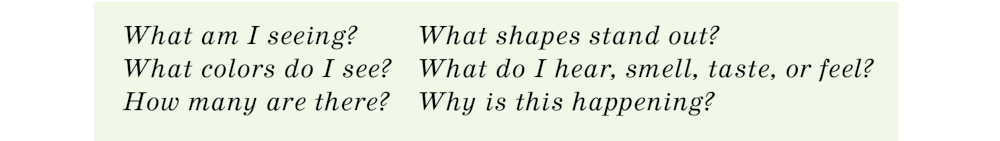

- Visualize different scenes. To do this, focus on a certain part of the story and ask yourself these questions about it:

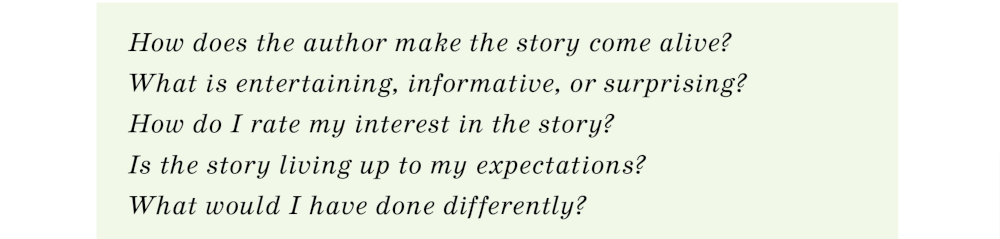

- Evaluate your reading. Ask yourself questions like these:

Helpful Hint

Team up with reading partners to discuss the story as you read. Check your understanding together. Also make “team” predictions and evaluations. Your partner’s thoughts and ideas can deepen your own understanding of the selection.

WOC 391

Page 391

After Reading

When you finish your reading, complete activities like the ones that follow.

Tips for Reviewing and Reflecting

■ Ask yourself a few important questions about the reading.

- Do I understand everything that happened?

- Can I describe the personalities of the main characters?

- Does the ending come as a surprise? Why or why not?

- Does anything in the story confuse me?

- What is the main point or theme of the story?

Helpful Hint

You may need to do some rereading and writing to answer these questions.

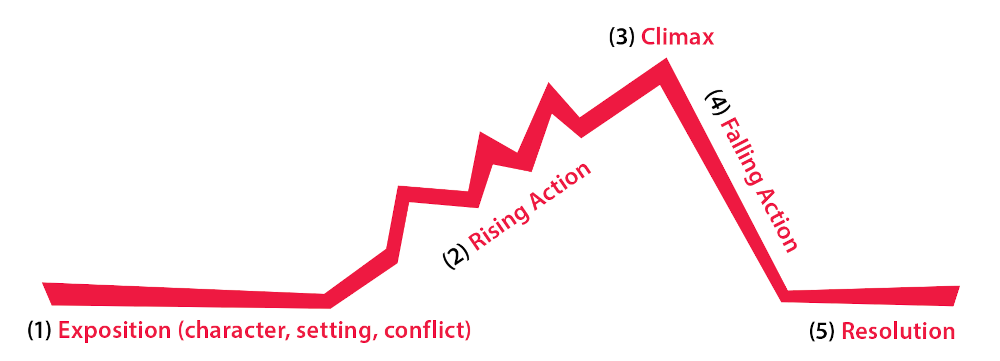

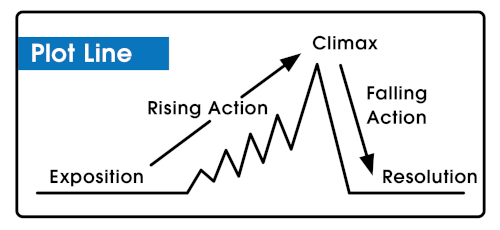

■ Create a plot diagram.

Identify the main events in the plot. The plot diagram below shows how the plot (main action) usually unfolds in a story. (Download your own plot diagram for analyzing fiction.)

- The exposition introduces characters, setting, and conflict.

- The rising action includes events that show how the main character deals with the conflict.

- The climax is the most exciting moment, when the main character faces the conflict directly.

- The falling action consists of events that lead to the resolution.

- The resolution is the way the story ends.

WOC 392

Page 392

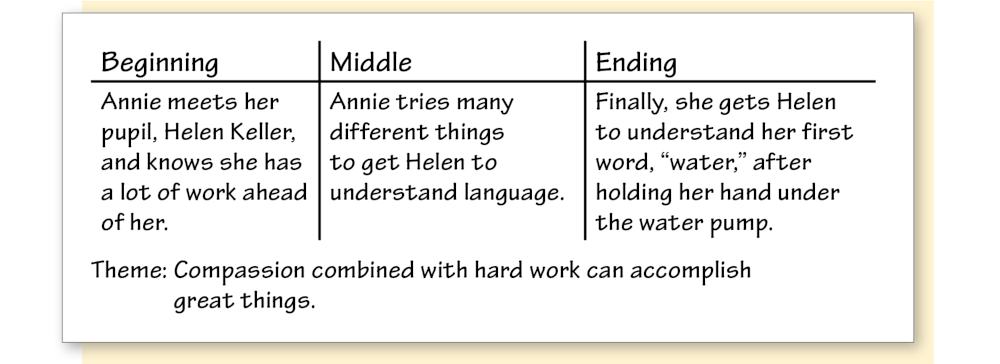

■ Chart the development of the main character.

You can track how a character changes by paying attention to what the person says, does, and thinks at different points. Recognizing this change may help you understand the story’s main theme. For example, in The Miracle Worker, Annie Sullivan’s actions as a teacher reveal the theme of this play.

Character Development Chart

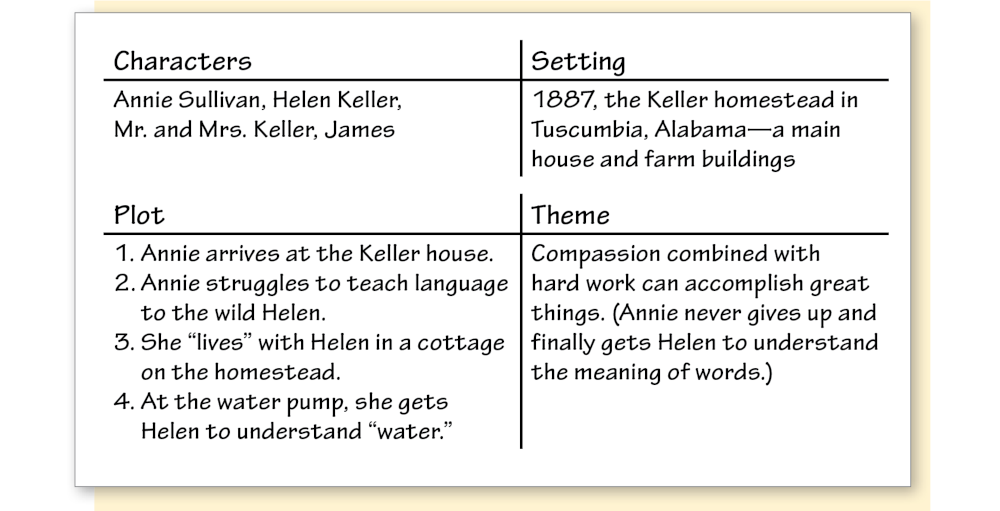

■ Fill in a fiction organizer.

To help you develop a full understanding of your reading, you can fill in a fiction organizer. In this type of graphic organizer, you identify the main elements of the story: characters, setting, plot, and theme.

Fiction Organizer

WOC 393

Page 393

Types of Literature

These two pages identify many of the common types of literature.

Allegory ■ A story representing an idea or a truth about life

Autobiography ■ A nonfiction account of the life of the writer

Biography ■ A writer’s nonfiction account of another person’s life

Comedy ■ Writing that deals with life, often poking fun at people’s mistakes

Drama ■ Writing that uses dialogue to share its message; meant to be performed in front of an audience

Epic ■ A long narrative poem telling of the deeds of a hero

Essay ■ Writing that expresses the writer’s opinion or shares information

Fable ■ A brief story that teaches a lesson and often uses talking animals as the main characters

Fantasy ■ A story set in an imaginary world in which the characters usually have supernatural powers or abilities

Farce ■ Literature based on a humorous and improbable plot

Folktale ■ A story passed from one generation to another (The characters are usually all good or all bad and in the end are rewarded or punished as they deserve.)

Graphic Novel ■ A novel told through a combination of words and image

Historical Fiction ■ An imaginary story based on a real time and place in history

Memoir ■ Writing based on the writer’s memory of a time, a place, or an incident

WOC 394

Page 394

Myth ■ A story intended to explain some mystery of nature or cultural belief (The gods and goddesses have supernatural powers, but the human characters usually do not.)

Novel ■ A book-length, fictional prose story (Because of its length, a novel’s plot can be complex, and the characters can be many faceted.)

Novella ■ Literature that is longer than a short story, but shorter and less complex than a full-length novel

Parable ■ A short story that explains a belief or moral principle

Parody ■ Literature that intentionally uses comic effect to mock a literary work or style

Play ■ (See drama.)

Poetry ■ A literary work that uses concise language to express ideas or emotions (Examples: ballad, blank verse, free verse, elegy, limerick, sonnet)

Prose ■ Literature that uses the familiar spoken form of language, sentence after sentence

Realism ■ Writing that attempts to show life as it really is

Science Fiction ■ Writing based on real or imaginary scientific developments

Short Story ■ Literature that can usually be read in one sitting (It contains only a few characters and focuses on one problem.)

Tall Tale ■ A humorous, exaggerated story often based on the life of a real person (The main character usually accomplishes impossible things.)

Tragedy ■ Literature in which the hero is destroyed because of some tragic flaw in character

Verse Novel ■ A novel told through the use of poetic form and language, featuring such techniques as rhyme, rhythm, metaphor, and symbolism

WOC 395

Page 395

Elements of Literature

The next two pages describe important elements or parts of literature. This information will help you discuss and write about novels, poetry, essays, and other literary works.

Action ■ Everything that happens in a story

Antagonist ■ The person or force that works against the hero of the story (See protagonist.)

Character ■ A person or an animal in a story

Characterization ■ The methods a writer uses to develop a character; here are three methods:

- Sharing the character’s thoughts, actions, and dialogue

- Describing the person’s appearance

- Revealing what others in the story think of this character

Conflict ■ A problem or struggle between two forces in a story; here are the five basic conflicts:

- Person Against Person: A problem between characters

- Person Against Self: A problem within a character’s own mind

- Person Against Society: A problem between a character and society, school, the law, or some tradition

- Person Against Nature: A problem between a character and some element of nature—a blizzard, a hurricane, and so on

- Person Against Destiny: A problem or struggle that appears to be well beyond a character’s control

Dialogue ■ The conversations between two or more characters

Foil ■ A character who serves as a contrast or challenge to the main character

Mood ■ The feeling or emotion a piece of literature creates in a reader

Moral ■ The lesson a story teaches

Narrator ■ The person or character who actually tells the story, giving background information and filling in details between portions of dialogue

Plot ■ The action that makes up the story, following a plan called the plot line

Plot Line ■ The planned action or series of events in a story (The basic parts of the plot line are the exposition, the rising action, the climax, the falling action, and the resolution.)

- Exposition: The opening part of a story (Usually, the characters are introduced, the background is explained, and the setting is described in this part.)

- Rising Action: The central part of the story during which a conflict is dealt with

- Climax: The moment when the conflict is strongest and the main character must act upon it

- Falling Action: The events leading to the resolution

- Resolution: The closing part of a story telling how the main character has changed

WOC 396

Page 396

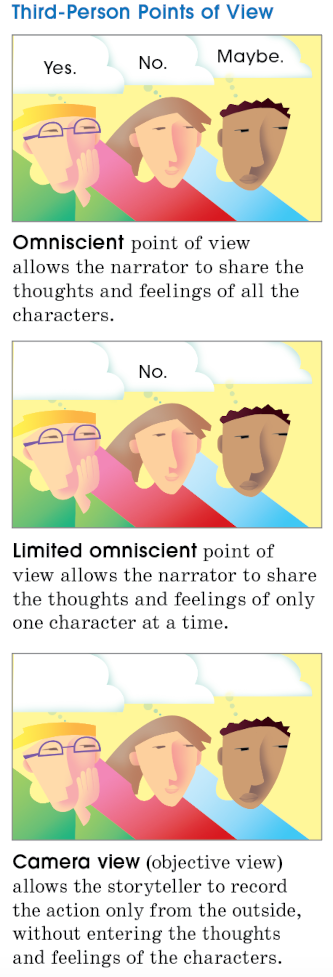

Point of View ■ The angle from which a story is told (The angle depends upon the narrator, or person telling the story.)

- First-Person Point of View This means that one of the characters is telling the story: “Linda is my older sister, beautiful and popular.”

- Third-Person Point of View In third person, someone from the outside of the story is telling it: “Linda is her older sister, beautiful and popular.” There are three third-person points of view: omniscient, limited omniscient, and camera view. (See the illustrations.)