WOC 262

Page 262

WOC 263

Page 263

Writing Stories

What’s so magical about tales around a campfire? Perhaps its the star-spangled heavens stretching blue-black overhead. Maybe it’s the hypnotic dance of yellow and red and blue flames over the logs. Or it might be the scent of roasting marshmallows with graham crackers and chocolate waiting nearby. But, really, the magic lies in the tales themselves, which have the power to transport you to another place and time and let you share your experience with fictional friends.

Human beings have been gathering around campfires and telling stories for as long as we’ve been human beings. The power of stories is primal. We all gratefully nestle into a good story as if it were a warm blanket. We no longer see with outward eyes, but instead with inward ones.

This chapter helps you write stories that transport readers, making them laugh or maybe even cry, and letting them explore their imaginations.

What’s Ahead

WOC 264

Page 264

How Stories Develop

A story is about people or creatures (characters) in a place and time (setting) struggling to accomplish something (plot) and learning something along the way (theme). Let’s take a look at the overall structure of an effective plot.

The Plot

The term plot refers to all of the action—the events that move a story along from start to finish. A plot has five basic parts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. The plot line that follows shows how these parts all work together.

Plot Line

A Closer Look at the Parts . . .

■ Exposition

The exposition is the beginning part of a story in which the characters, setting, and conflict are usually introduced. There is at least one main character in all stories and, almost always, one or more supporting or secondary characters. The setting is where and when the story takes place, and the conflict is the main problem that fuels the action. Here is a summary of the exposition in one story.

Callum is a shy seventh grader who receives a wristwatch for his birthday. Callum had wanted a digital watch, but this one is analog and needs to be wound. Worse yet, it doesn’t keep accurate time. Frustrated, Callum tries to reset the watch, only to discover that by moving the hands backward and forward, he can travel through time.

WOC 265

Page 265

■ Rising Action

In the rising action, the main character tries to solve his or her problem, getting involved in at least two or three important actions along the way. This builds suspense into the story.

First action: Callum and his watch travel backward in time to earlier that day, when Bruce Buckstead, the school bully, insulted him. This time, Callum has the perfect comeback ready, and the bully stalks away.

Second action: Callum returns to the present and begins using his watch whenever things don’t go his way. If he trips, he goes back and corrects it. If he doesn’t know the correct answer to a question, he finds out and then goes back in time and answers correctly.

Third action: Soon, Callum is considered the smartest, funniest, fastest, most amazing kid at his school. Bruce Buckstead becomes jealous and corners Callum in a hallway.

■ Climax

The climax is the most exciting or important part in a story. At this point, the main character comes face-to-face with his or her problem. (All of the action leads up to the climax.) This part is sometimes called the turning point.

Bruce tries to punch Callum, but Callum turns the watch back and dodges just in time. A crowd of kids gathers, watching Callum dodge punch after punch. But during one dodge, Callum’s watch hits the wall and breaks. He’s defenseless, and Bruce closes in.

■ Falling Action

In this part, the main character learns to deal with life “after the climax.” Perhaps the person makes a new discovery about life or comes to understand things a little better.

Bruce never touches Callum, though, because the other kids tell him to back off. They say they’re done being bullied, and that if Bruce wants to get at Callum, he’s got to go through all of them.

■ Resolution

The resolution brings a story to a natural, surprising, or thought-provoking conclusion. (The falling action and the resolution often are very closely related.)

Though Callum has lost his magic watch, he’s gained a whole lot of new friends—and a lot more confidence.

WOC 266

Page 266

Short Story

The following story by student writer Jon Roberts tells about a middle schooler’s strategy for asking a friend to go with him to see a movie.

Opposite Day

Exposition:

The beginning introduces the characters, setting, and conflict. Ted Demeter arrived early to jazz band practice and went to assemble his trombone. He looked at his reflection in the shiny bell and finger-combed his brown hair. His green eyes sparkled. Today was the day. Today he would ask Joanna Fetchner to go out with him. He had everything planned, and he just hoped she would say, “No.”

Joanna arrived. Ted couldn’t see her at the band room door—long blonde hair flipping and smile flashing—but he could hear her laughing voice as she talked with her friend, Lis, who played trumpet. As Joanna approached, Ted quickly snapped his trombone case closed.

Dialogue shows the personality of the characters. “Hi,” said Joanna, reaching for her trombone case.

“Bye,” replied Ted, waving and blushing. He ducked away.

Ted went to the trombone section and sat down in Joanna’s seat—the second-chair spot. He was setting up his music folder on the stand when Joanna approached.

Rising Action:

A series of actions develops the main conflict. “Okay, Teddy, move over,” Joanna said, smiling.

“This is my chair.”

“You’re first chair.”

He grinned. “It’s Same Day!”

“What? Same Day? I’ve heard of Opposite Day . . . “

“It’s Same Day,” Ted insisted, gesturing toward the first chair spot. “Stand up!”

Joanna’s brow furrowed, but she sat down. Then she laughed. “Oh! ‘It’s Same Day,’ is exactly what you wouldn’t say if it were actually Opposite Day.”

“You’re exactly wrong,” Teddy said approvingly.

The stakes get higher. The two trombone players sat side by side as other jazz band members filed into their seats. The director, Mr. Cross, stepped up to the podium. His meaty face was red like his name. “Why is Joanna in the first chair?” he barked.

Joanna blushed as red as Mr. Cross, but Ted blurted, “It’s Joanna’s birthday today!”

Mr. Cross scowled, “Is that true, Joanna?”

“N—” Joanna began, but Ted elbowed her. She yammered, “Y-y-yes it is.”

Lis in the trumpet section glared incredulously at her, but Mr. Cross led the group in singing “Happy Birthday.” Ted sang loudest of all while Joanna shrank beside him.

After the song, Joanna growled, “Thanks, that was really nice.”

Ted said sincerely, “I don’t apologize.”

Joanna replied, “I don’t accept your apology.”

Drawing a deep breath, Ted ventured, “Um, Joanna, there’s nothing I want to ask you.”

“Then don’t.”

Mr. Cross called out the song “Nemesis,” which had a trombone solo in the middle of it. When the time came for the solo, Ted played all the notes backward. Mr. Cross stared at him, then struck the podium with his baton. “Wow! No wonder you’re not first chair anymore. Let’s hear Joanna play the solo this time.”

The band launched again into “Nemesis,” and when the trombone solo came, Joanna played it backward. Mr. Cross stopped the band, whipped off his glasses, gawked at his score, and then said, “You’re lucky it’s your birthday!” He rifled through his music, “Let’s play something without a trombone solo. How about ‘In the Mood’?”

Climax:

Tension builds to a crisis point. As the band switched their music, Joanna said, “So, what were you not going to ask me?”

“I was hoping,” Ted began, but his throat clamped shut.

Joanna pinned him with her bright blue eyes. “What?”

“I was hoping,” Ted repeated, “that you wouldn’t go to the movies with me tonight.”

Joanna stared, wide-eyed. “I definitely won’t.”

Ted wished he could crawl into a hole. It was his worst nightmare.

Joanna put her hand on his knee. “I would hate to go.”

Suddenly remembering, Ted shook his head. “Well, I would hate to take you.”

Falling Action and Resolution:

The final action leads to an amusing conclusion. As Mr. Cross raised his baton, the two trombonists straightened, raising their instruments.

“I won’t be at your house at 7:00 p.m.” Ted said.

“I won’t be ready,” Joanna replied.

Ted smiled. “I sure am glad it’s Same Day!”

Joanna winked at him, and they began to play.

WOC 268

Page 268

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Creating a Character

Interesting characters make interesting stories. The desires of the characters shape the plot. By creating a character and understanding the person inside and out, you’ll soon know what type of story you want to tell. Jon created Ted Demeter by filling out a character creator chart.

Character Creator Chart

WOC 269

Page 269

Forming a Conflict

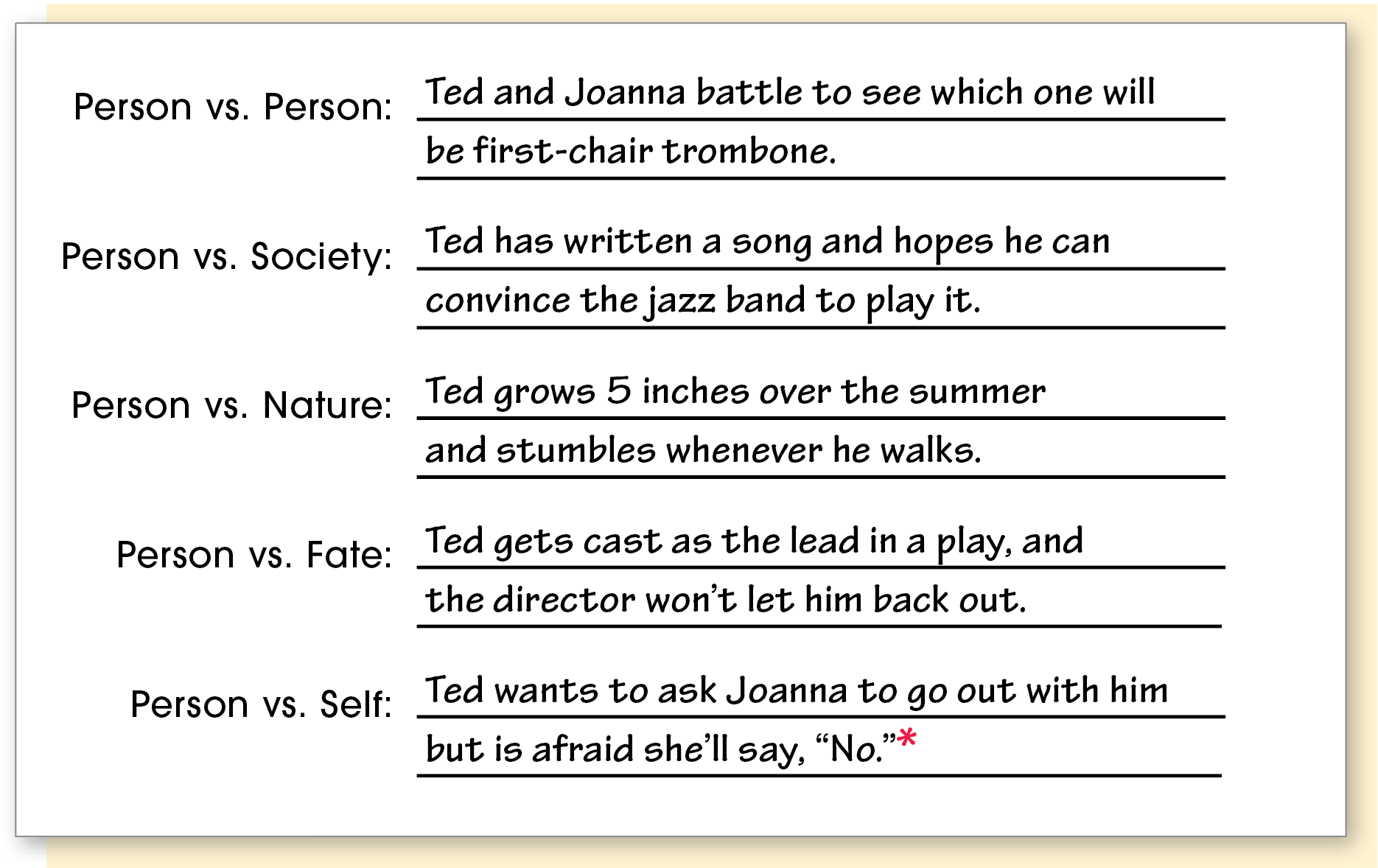

Once you have created a strong character, think about what challenge or problem the character would be likely to have. The main character’s problem is the conflict, which can come in several forms. Jon brainstormed different conflicts for his character. (Download a conflict chart.)

Creating a Plot

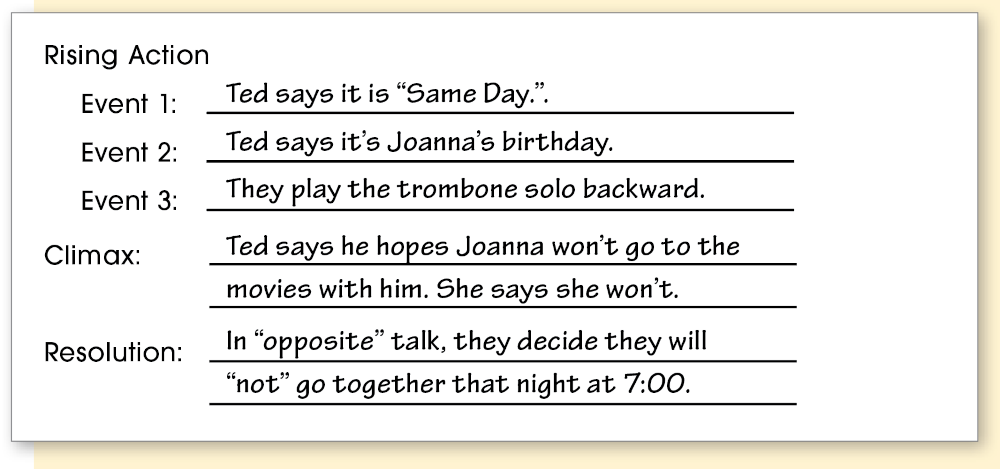

After choosing a conflict, imagine a set of events that demonstrate the conflict. Each event should challenge the main character, building toward a climax—the most exciting part. Jon created the following plot. (Download a plot chart.)

WOC 270

Page 270

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

After completing the prewriting activities described on pages 268–269, begin writing your first draft.

Exposition ■ Grab your reader’s attention by starting your story right in the middle of the action. As you develop this part, try to identify the main character, the setting, and the main problem. (See the beginning of the short story, page 266, for an example.)

Rising Action and Climax ■ Let your characters’ conversations (dialogue) and actions move the story along as much as possible. (See “Writing Dialogue” below.)

Falling Action and Resolution ■ In most stories, the action quickly comes to a close after the climax. What happens in this part should show how the main character has been affected by the climax.

Helpful Hint

Keep the exposition and resolution quick. Readers want to get to the “good stuff”—the rising action, climax, and falling action.

Writing Dialogue

Refer to these guidelines when you develop dialogue in your short stories. (Also study the dialogue in the short story on pages 266–267.)

- Write the way people actually speak. (People often interrupt each other.)

- Focus on the speaker’s beliefs or problem. (Generally, one speaker’s beliefs clash with another’s.)

- Keep the conversation moving along. (Characters don’t have to say everything. Leave some things to the reader’s imagination.)

- Present the dialogue so it is easy to read. (Indent every time someone new speaks and identify the speaker if it isn’t clear who is talking. See pages 491–492 for help with punctuation.)

WOC 271

Page 271

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving Your Writing

Ask yourself the following questions when you review and revise your first draft. (Download these questions as a checklist.)

- Do the characters’ words and actions seem natural? (We wouldn’t expect the neighborhood bully to talk like a college professor.)

- Is there a real or believable conflict that keeps the story going?

- Do all of the characters play an important role in the story? Are all of the conversations, explanations, and events important? (Make sure that your story moves along at a steady clip. You don’t have to tell the reader everything.)

- Is the main character put to the test at the climax in the story? (The main character should undergo some change because of this event.)

- Does the story make sense and contain enough detail and background information? (Fill in any holes or gaps in the story line.)

- Does the narrator’s voice engage the reader?

- Do the sentences read smoothly?

- Do all of the words “work” within the context of the story?

- Are punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and grammar correct?

Topping Off Your Writing

Here’s how to top off your writing with a good title. Think of your title as fish bait: It should look juicy, it should dance slightly, and it should have a hook in it.

- To look juicy, a title must contain strong, colorful words.

(The Black Stallion, Brave New World) - To dance, it must have rhythm.

(The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, not Wardrobe World) - And to hook your reader, it must grab the imagination.

(Never Cry Wolf, not A Story About the Wilderness)

List a number of possible titles; then select the one that provides the best bait for your reader.

WOC 272

Page 272

A Short-Story Sampler

Here are brief descriptions of popular short-story types. Use these as starting points for your own stories.

■ Mystery

Think of a crime, a list of suspects, a criminal, and a star detective, and you’re ready to write your first whodunit. Pay close attention to mysteries on TV to see how screenwriters develop their stories, or try reading books by Agatha Christie, Joan Lowery Nixon, Alane Ferguson, Tony Hillerman, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

■ Fantasy

Add some fantastic elements to real-world situations and create a fantasy. Think of some of your favorite childhood stories for ideas. Many of these stories contain fantastic elements (animals that talk, bathtubs that become pirate ships, and so on.). Joan Aiken, Lloyd Alexander, and J. R. R. Tolkien are fantasy writers you may enjoy reading.

■ Science Fiction

Imagine a world 100 years after a nuclear war. Who would be living? What would life be like? What would the people know about life as it was before the war? This is science fiction—when life as we know it is dramatically altered in some way. Read “By the Waters of Babylon” by Stephen Vincent Benét for a great story along these lines.

■ Myth

All of us have a fascination with myths. They are wonderful stories that attempt to explain some natural phenomenon. Create your own myth, explaining why we cry, why early summer is tornado season, or, perhaps, why gold is so valued. For inspiring stories, read ancient myths from cultures such as Greece, Egypt, Norway, or the indigenous people of North America.

■ Fable

Write a brief story that makes a point, teaches, or advises. There are two basic ways to do this: Start with a moral and develop a story that leads up to it, or develop a story and decide afterward what it teaches or advises. The ancient writer Aesop wrote many fables.