WOC 145

Page 145

Writing Personal Narratives

“Tell us the one about when your computer caught on fire.”

Sometimes, the worst experiences become the best stories. Things that seem bewildering or tragic at the time might seem hilarious later. People will ask you to tell these stories over and over, and as you do, you’ll get better at relaying them. You’ll create suspense and emphasize the funny parts, even adding gestures and facial expressions.

You can also relay such stories in writing. Establish the place and time, introduce the main people involved, and reveal a problem. Then tell your real-life story. Make it exciting and fun so that people will want to read it again and again.

This chapter provides a model personal narrative about a funny experience, followed by guidelines to help you capture your own memories.

What’s Ahead

WOC 146

Page 146

Understanding Narrative Writing

What makes you different from everyone else on the planet? Your memories. Your life is a movie that only you experience—until you write a personal narrative to share memories with others.

Link to the Traits

When writing, pay special attention to the traits of ideas, organization, and voice.

Ideas ■

Select a memory that you really want to share. Include specific details that let readers experience the memory as though they had been there.

Organization ■

Relay events in chronological order. To describe locations, you can use spatial organization.

Voice ■

Create a storytelling voice that connects with the reader—welcoming, honest, sincere, and engaging.

WOC 147

Page 147

Personal Narrative

In the following personal narrative, student Evan Connolly shares a memorable experience about coming home late one evening.

Beware the Porch Bandit!

Beginning:

The writer sets the scene, introducing the problem. One night, Mom had to work late, and I was playing board games with friends, leaving my younger brother Bob at home alone. I got back before Mom, and the house was dark, the doors locked tight.

I pounded on the back door. “Bob, let me in. It’s Evan!”

No answer. Bob must have gone to bed.

I circled around the house and entered our screened-in front porch. The front door was locked, just like the back. I rang the bell repeatedly. “Bob! Come on! Let me in.”

Middle Paragraphs:

Sensory details make the descriptions clear. Then I noticed that the window between our front room and porch was open to let the cats out. “Guess I’ll be a cat burglar tonight,” I muttered.

I stuck my leg in the window and ducked down to crouch through. My foot came down on a flowerpot, tipping it over. Clank! Crack! Boom! The pot shattered on the floor, spaying damp earth around a ruined aloe.

Dialogue moves the action forward. A shout came from upstairs, my brother Bob making his voice really low. “I hear you! If you’re down there when I arrive, get ready for a bat!”

I yelled, “It’s me, Bob! It’s Evan!”

He didn’t hear because now he was barking like a rottweiler, which we didn’t have. “You better run before my dog gets you!” Bob warned, following with more rabid barking.

“Bob! It’s me!” I cried, though I was laughing so hard I could barely get the words out. “It’s your brother, Evan!”

“I’ll teach you a lesson, you porch bandit!” Bob bellowed, charging down the stairs while baying and slavering like a pack of wild dogs. He flung open the stairway door and lifted a baseball bat over his head just as I flicked on the light.

Ending:

The ending brings the story to a humorous close. “Bob! It’s me, Evan!” I exclaimed through laughter.

“He flushed red with embarrassment, lowering the bat. “Stupid porch bandit!”

“I grinned at him. “You did a good job defending the old homestead, Bob. Let me see if I can find you a doggie treat.”

WOC 148

Page 148

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Any memorable event is a good topic for a personal narrative. The event doesn’t have to be big (driving the Alaska Highway), just interesting. Something small in scale (the first friend you made) might make a better narrative.

Helpful Hint

Think of events that took place within a fairly short period of time. Evan Connolly’s story about returning home one night is based on an experience that lasted only 5 minutes.

Gathering Details

The experience you choose to write about may be very clear in your mind. If this is the case, you may do very little collecting. A simple, quick listing of the basic facts may be enough. Just jot down things as they happened. Or you may want to use a 5 W’s chart to collect this information. (See page 35.)

Once you finish your list, review all of the details you’ve included, using the following points as a general guide:

- Get rid of any information that is not important.

- Move ideas around if they’re not in the right order.

- Add important details you forgot.

- Use your list to begin your rough draft.

WOC 149

Page 149

Using Sensory Details

One way to make a narrative come to life is to use sensory details. Sensory details let the reader see, hear, smell, taste, and touch the experience—that is, live it. Evan created this sensory chart.

Sensory Chart

Different sensory details have different effects on the reader.

- Seeing is believing: Evan didn’t just tell the reader that Bob was afraid of burglars but showed him bursting through the door with bat held high.

- Hearing is communicating: Hearing conveys what other people think or feel. In Evan’s story, the banging and doorbell indicated someone wanted to come in, and Bob’s yelling and barking indicated that he thought Evan was a prowler.

- Touching is feeling: Some touch words such as rough, sharp, blunt, and hard create negative emotions. Other touch words such as smooth, soft, warm, and solid create positive emotions. Evan’s detail of pounding on the door creates a feeling of impatience and urgency.

- Smelling is evaluating: People use their sense of smell to decide if something is good or bad: Is the milk fresh or sour? Are the clothes clean or dirty? A sweet smell will comfort your reader, but a rank one will set the reader on edge. The detail of spraying damp earth around a ruined aloe creates a feeling of minor catastrophe.

- Tasting is desiring: Taste words such as tangy, sweet, ripe, and juicy can make readers desire what they are connected to. Think about a sweet bike or a juicy offer. Other taste words such as bland, bitter, acidic, and stale can remove desire. Think about an acidic comment or a stale idea.

WOC 150

Page 150

Writing ■ Developing the First Draft

As you write your narrative, focus on the people involved, the place and time of the event, what happened, and what people said. Use the following basic tools to write your narrative:

1. Action: Use active verbs so the reader can experience what is happening.

I stuck my leg through the window and ducked down to crouch through.

2. Dialogue: Capture the unique voice of different people involved in the situation. Use quotation marks around their words, and tell who said what.

“You better run before my dog gets you!” Bob warned, following with more rabid barking.

3. Description: Use sensory details to describe people, places, and things.

My foot came down on a flowerpot, tipping it over. Clank! Crack! Boom! The pot shattered on the floor . . .

Beginning ■ Evan Connolly’s narrative sets up the situation and leads immediately to the problem: His brother is home alone and has locked Evan out of the house before going to bed. In the same way, you can quickly indicate the setting, name the people, and present a problem that they face. Then relive your memory with readers coming along.

Middle ■ Organize your details in the order that they happened (chronologically). This way, the reader gets to experience the event along with you. Use description, action, and dialogue to tell your story. Build up to the most exciting point. In Evan’s narrative, the most exciting point is when his brother bursts through the door with bat raised.

Good Thinking

Remember to write down only the important parts of the event. As novelist Elmore Leonard says, “I try to leave out the parts that people skip.” Imagine telling the story to a friend, and whenever the friend would say, “Get on with it,” well, get on with it!

Ending ■ After the most exciting part, bring your narrative quickly to a close. Leave the reader with a final strong impression—or a laugh.

WOC 151

Page 151

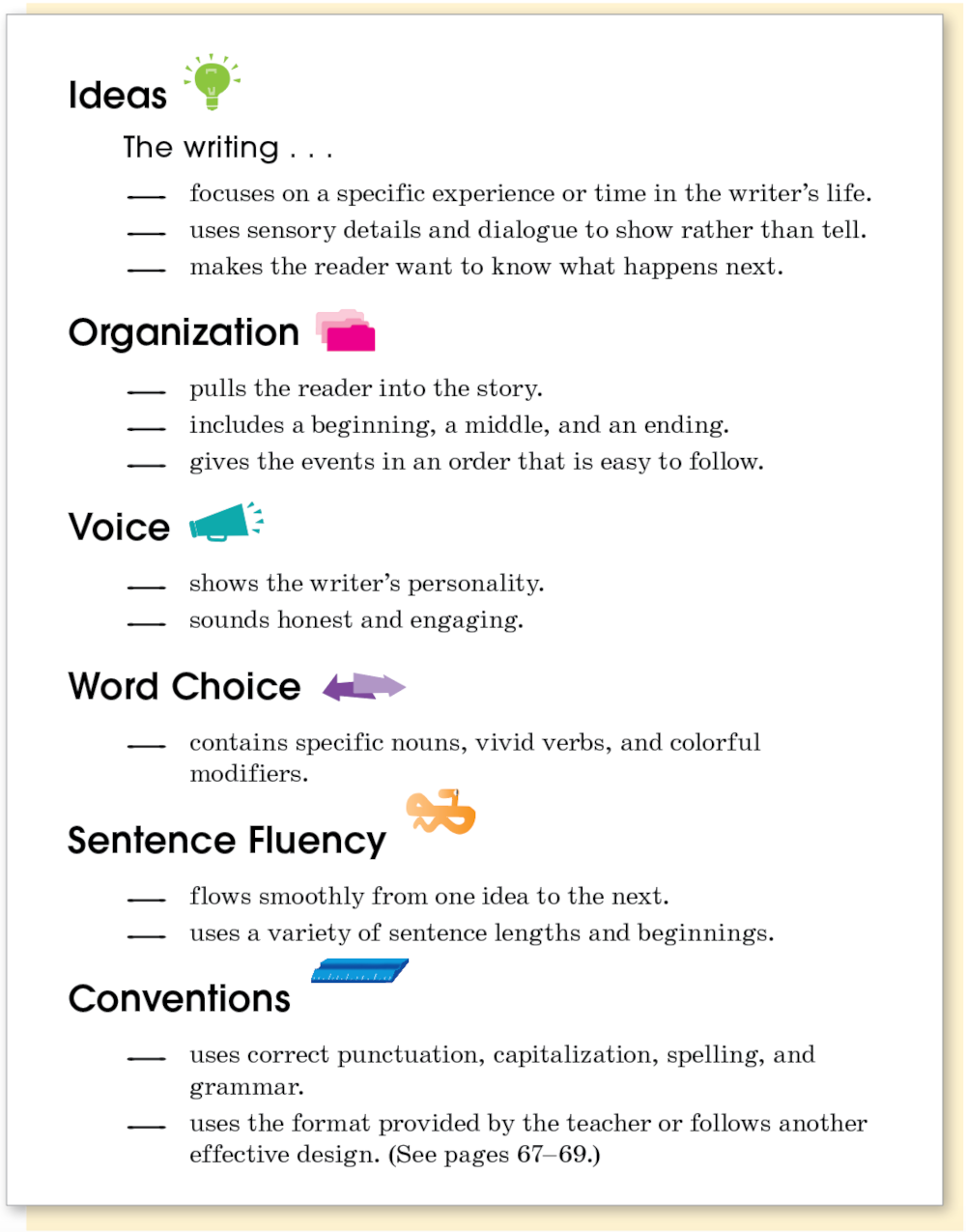

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving Your Writing

Use the following checklist to revise and edit your narrative.

_____ Ideas Do I focus on one experience? Do I include action and dialogue? Do I use sensory details in my descriptions?

_____ Organization Do my beginning and ending work well? Are my details in time order?

_____ Voice Is my storytelling voice engaging?

_____ Word Choice Have I used specific nouns, active verbs, and descriptive modifiers?

_____ Sentences Does my narrative read smoothly?

_____ Conventions Have I checked punctuation (see below), capitalization, spelling, and grammar?

A Closer Look at Editing ■ Quotation Marks

As you edit your narrative, make sure you correctly use quotation marks and other punctuation around quotation marks. Follow these rules:

- Put quotation marks before and after the words spoken by someone.

“Bob, come on! Let me in!”

- When a period or comma follows the quotation, place the period or comma before the quotation mark.

“Guess I’ll be a cat burglar tonight,” I muttered.

- When a question mark or exclamation point follows the quotation, put the punctuation before the quotation mark if it belongs with the quotation. Otherwise, put it after.

“Bob! It’ me, Evan!” I exclaimed through laughter.

He flushed red with embarrassment, lowering the bat. “Stupid porch bandit!”

- When a semicolon or colon follows the quotation, place it after the quotation mark.

Bob said, “Keep your doggie treats”; even so, he stalked to the kitchen to console himself with ice cream.

Helpful Hint

For more rules about using quotation marks, see 491.1–492.3.