WOC 209

Page 209

Other Forms of Persuasive Writing

An old expression goes, “If you can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen.” You might instead say, “If you can’t stand the heat, get a fan.” You don’t have to put up with problems that you can solve. Sometimes you can solve the problem yourself, and other times you can get help—perhaps by writing a problem-solution letter. This chapter shows how.

You will also learn how to create a persuasive poster and develop a brochure—two more ways to convince others. And if you want just to complain about some minor problem, why not create a pet peeve essay? Finally, you will learn how to form a response to a persuasive prompt.

What’s Ahead

WOC 210

Page 210

Problem-Solution Letter

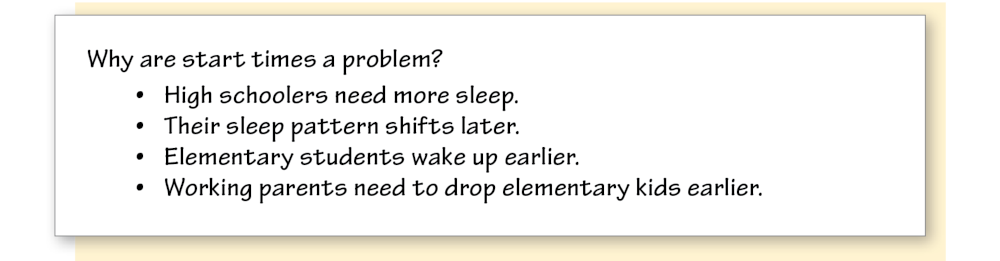

Student Douglas Previn wrote the following problem-solution letter to the president of his school board. He outlined a problem (school start times) and argued for a solution.

204 Center Street

Springfield, NY 13468

November 7, 2025

Mrs. Anita Juarez, President

Otsego Unified School Board

534 Lincoln Street

Springfield, NY 13468

Dear Mrs. Juarez:

Beginning:

The beginning effectively leads up to the thesis statement (underlined). I’m writing with a concern and a suggestion about school start times. Currently, elementary schools in the district start latest, with classes beginning at 8:30, and the high school starts earliest, with classes beginning at 7:30. This schedule ignores the sleeping patterns of students and makes mornings difficult for working families. I would recommend that we change to the following start schedule: elementary at 7:30 a.m., middle at 8:00 a.m., and high school at 8:30 a.m.

Middle:

The first middle paragraph explains the problem. Such a shift in schedule would better match sleep patterns. According to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, adolescent sleep patterns shift two hours later than children’s patterns. That means that instead of falling asleep at 9:00 p.m. on average, teenagers can’t sleep until about 11:00 p.m. On top of that, teens need 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night, more than children or adults. That means, at minimum, teens should be able to sleep until 7:00 a.m., which is not possible with the current start times. As a result, most teens are sleep deprived, which leads to physical and mental health problems as well as less learning and lower grades.

The second middle paragraph argues for a solution. In addition, our current start time makes mornings difficult for working families with young children. Students in elementary school tend to wake up early, so they have extra time in the morning. If parents are working, many of them need to be at work at 8:00 a.m. The elementary start time of 8:30 a.m. means that many parents have to drop their children off at school by 7:40 a.m., making students spend 50 minutes per day in the cafeteria waiting for school to start. If the elementary start time were moved to 7:30 a.m., the schedule would work better for these families.

This middle paragraph answers objections to the proposal. Some might object to shifting school start times, saying that high schoolers need time for after-school sports and activities as well as jobs. These are important concerns, but they are not as important as a student’s education and health. If high schoolers are struggling to stay awake in the first two hours of the school day, they will not be learning much. Also, the shift will reduce after-school time by just an hour, which means that most activities will be unaffected.

Ending:

The ending paragraphs review the benefits of the solution and call the reader to act. A shift in start times would solve numerous problems. It would help high schoolers have more healthy sleep patterns and struggle less in class. It would also help working families of young students drop off their children and get to work on time.

Please consider my suggestion of swapping school start times to have elementary schools start at 7:30 a.m. and high schools start at 8:30 a.m.

Sincerely,

Douglas Previn

WOC 212

Page 212

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Selecting a Problem

When choosing a topic, consider problems in your home, school, or community. Once you have a topic in mind, identify a person or group who can help you solve the problem. Douglas had a strong opinion about school start times and wanted to persuade the school board to consider a shift in schedule.

Gathering Details

Next, you will need to gather supporting information for your letter. You can do this by listing important questions (and answers) about your topic. Find out why the problem exists and why it should be solved. Here is the first part of Douglas’s list:

Details List

You will also need to propose solutions to the problem. Douglas completed a sentence starter to think about his solution.

Sentence Starter

WOC 213

Page 213

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

Beginning ■ Introduce the problem in an interesting way and then state the focus of your letter. Douglas introduces his letter by stating his reason for writing. Here are three other attention-grabbing strategies to consider:

- Ask a question.

Shouldn’t our school start times reflect the sleep patterns of students at different ages?

- Quote someone.

“I’m usually not even awake until I hit third hour,” said Liam Bell. And he’s not alone.

- Share an experience.

Yesterday in homeroom, the teacher just told everybody to take a 15 minute nap.

Middle ■ If you have introduced the problem and solution in the first paragraph, use your middle paragraphs to argue for the solution. Show the benefits of the solution. Also, answer any objections.

- Counterargument:

Some might object to shifting school start times, saying that high schoolers need time for after-school sports . . . These are important concerns, but they are not as important as a student’s education. . . .

Ending ■ Review your solution and call the reader to act:

- Call to action:

Please consider my suggestion of swapping school start times to have elementary schools start at 7:30 a.m. and high schools start at 8:30 a.m.

Helpful Hint

Use a variety of details to make your argument. Douglas refers to sleep science as well as the schedules of working families to argue his point.

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving the Writing

Use this checklist to help you revise and edit your letter.

Revising Checklist

_____ Ideas Do I focus on a clear problem and solution?

_____ Organization Does my letter have a clear beginning, middle, and ending?

_____ Voice Does my voice sound polite, yet persuasive?

_____ Word Choice Have I used specific nouns and persuasive verbs?

_____ Sentences Do my sentences read smoothly?

_____ Conventions Is my writing free of errors?

WOC 214

Page 214

Persuasive Poster and Brochure

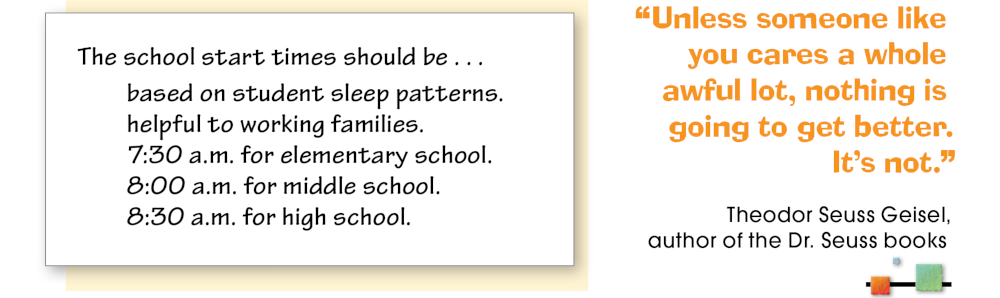

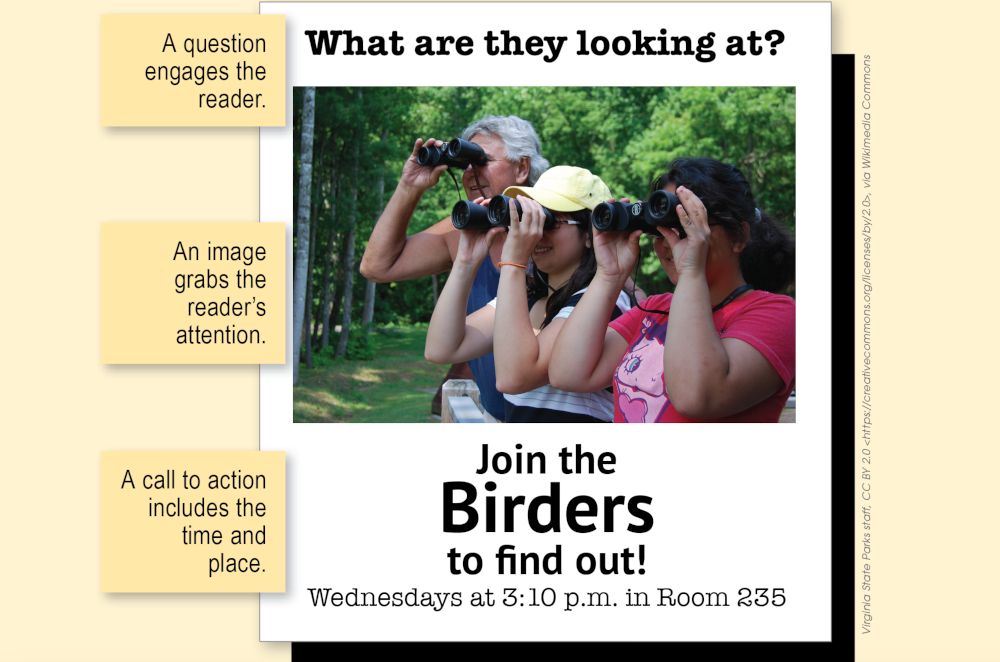

Persuasive writing can combine with images in a poster or brochure, convincing people to join a club or attend an event. The poster and brochure below were created to work together, promoting a middle school birding club.

Poster

WOC 215

Page 215

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■

Selecting a Topic ■ Think of a club, sport, activity, or event you want to promote in your school or community.

Gathering Details ■ Answer each of the 5 W’s about the event—who, what, where, when, why.

Focusing Your Thoughts■ Think about what your audience wants. Ask yourself how your subject meets the audience’s needs. Then write a persuasive pitch that connects to the audience’s need:

My audience wants . . . to see birds and have fun with other people.

Persuasive pitch: What are they looking at? Join the Birders to find out!

Writing ■

Connecting Your Ideas ■ Create a poster or brochure that features your persuasive pitch. Add an image or two that will support your pitch. Then provide information to answer the 5 W’s. Design your poster or brochure to effectively connect words and images.

Revising ■

Improving Your Writing ■ Make your poster or brochure better. (Download a revising and editing checklist.)

- Does my persuasive pitch connect the event to the audience?

- Do my images support my persuasive pitch?

- Have I answered all 5 W’s?

- Have I encouraged the viewer/reader to act?

- Is my poster/brochure eye-catching and well designed?

Editing ■ and Proofreading ■

Checking for Conventions ■ Polish your poster or brochure. (Download a revising and editing checklist.)

- Have I double-checked all facts (dates, times, locations, costs, names)?

- Have I correctly capitalized first words and proper nouns?

- Have I checked spelling and watched for easily confused words?

WOC 216

Page 216

Pet Peeve Essay

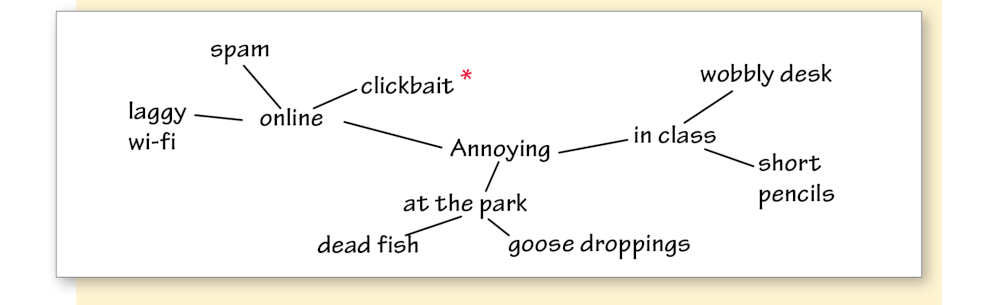

In the following pet peeve essay, student writer Roshawn Andrews expresses his frustration about an annoying feature of the Internet. His rant is clever, funny, and inventive.

Eat Only Donuts and Lose 20 Pounds!

Beginning:

The title demonstrates the problem of clickbait, and the thesis statement itself is clickbait (underlined). Scientists have discovered that pregnant women who eat only donuts on the day of delivery can still lose up to 20 pounds by giving birth! Gotcha! That’s what’s called a clickbait headline. It promises big and delivers next to nothing. These deceitful headlines are annoying, and they are everywhere, tempting you to click. But beware. Clickbait has been proven to cause thick coats of body hair and squeaking in laboratory rats.

Middle:

The writer uses a metaphor and funny examples. There, I did it again. Even my thesis statement is clickbait!

Clickbait is the Internet’s version of a lame pickup line. “Are you from Tennessee, because you’re the only 10 I see!” It’s a desperate ploy to get attention, and it’s just pathetic. How about this headline: “Olny a ginues can raed tihs setnecen! Laren mroe!”? The problem is, plenty of normal people can read those sentences, and no actual genius would click to “Laren mroe!”

“Elvis and Michael Jackson spotted together in Vegas!” Wow! That’s amazing . . . except that they were spotted together in 1974, which is hardly news, nor amazing. But since you clicked on the headline, the ten advertisers on each page of the article get seen, and your browser will now try to sell you T-shirts with Elvis and Michael Jackson.

That’s the secret of clickbait. Your attention is worth something. In fact, it is worth a lot. Clickbait headlines are the slot machines of the Internet. “Try Your Luck for a Nickle!” Why not? It’s just a nickle. But an hour later, you’ve spent all your attention on worthless nothing. Nickle by nickle, clickbait has plucked your mind away.

Ending:

The writer draws the rant to a humorous close. So learn to recognize clickbait. If it sounds too amazing or weird or profitable to be true, it is probably clickbait. There’s only one way to be safe from it: Click here for the last clickbait protector you will ever need!

WOC 217

Page 217

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Picking a pet peeve topic is easy. You just need to think of something seemingly unimportant that really bugs you. Roshawn used a cluster to find his topic.

Gathering Details

Once you have a topic, consider specific experiences involving the pet peeve, why it upsets you, and how you can remedy the situation. Roshawn gathered details by freewriting about the times when clickbait really upset him. (See page 34 for information about freewriting.)

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

Beginning ■ Grab the reader’s attention and reveal your true feelings about your pet peeve. Roshawn introduces clickbait by using a clickbait title and thesis statement.

Middle ■ Help readers really feel your annoyance. Remember to be funny, not just whiny.

Ending ■ Bring your rant to a fitting conclusion. Roshawn acts as if he is going to provide you with the secret to avoiding clickbait, but then includes a fake link that is itself clickbait.

Good Thinking

Pet peeve essays have an edge to them. One way to do this is to use sarcasm, or a mocking tone.

WOC 218

Page 218

Revising ■ and Editing ■

Revising focuses on large-scale improvements—adding, moving, rearranging, and rewriting parts of your essay. Editing focuses on small-scale improvements by correcting convention errors (punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and grammar). A checklist like this one can help you revise and edit your pet peeve essay.

Pet Peeve Revising and Editing Checklist

WOC 219

Page 219

Responding to a Persuasive Prompt

Prompt:

A “pain point” is a persistent or recurring problem in a system or product. What pain points are there in your school or community? Explain the source of the pain, and then argue for some strong solutions to eliminate or lessen the problem.

Prompt Analysis

■ Purpose: To explain a problem and argue for solutions

■ Audience: Test grader

■ Subject: A pain point in the school or community

■ Type: Problem-solution essay

Planning Quick List

Cliques in middle school

— Based on status

— Rules for who’s “in” and “out”

— Make friends instead of cliques

— Be independent

— Show compassion

Response

Avoiding Middle School Cliques

Beginning:

The writer introduces the topic and states her opinion. Every middle schooler want to have friends and to belong. Those are normal desires. But when the wish for friends turns exclusive, focusing on status and who’s in and who’s out, a clique has formed. Cliques use peer pressure to force their members to think, talk, act, and even dress in a specific way. Cliques may seem like friendship and belonging, but they really are the opposite, and students need to learn how to avoid them.

Middle:

This paragraph analyzes the problem. Cliques are basically middle-school tribes. Are you a jock, nerd, prep, goth, metalhead, popular girl, or what? At first, you might be attracted to hang with your tribe because of similar interests and attitudes. But when the group begins to control you, telling you what music to like and what people to talk to, you know that now you are in a clique.

The next paragraph shows the harm done. Cliques harm people both inside and outside. Those on the inside work hard to stay in. They live in constant fear that they will be banished from the group. Those on the outside look inward, wishing they could belong. People who aren’t in cliques are more likely to be bullied by others, but people who are in cliques often are bullied by their so-called “friends.”

The writer argues for ways to avoid cliques. The first way to avoid cliques is to seek real friends. They care about you rather than about what you can do for them. Real friends let you be yourself and don’t demand that you act a certain way. When “friends” make demands on you, tell them you can make up your own mind how you’ll look and act and think. If those people reject you, they were never friends to begin with.

The writer offers three solutions. Don’t be afraid to be independent. That can be really hard in middle school, but if you look around, you’ll see a lot of other students being independent as well. Make friends with them. Care about them. Really connect. And when another student comes along who does the same, make friends with that person.

Show compassion. If someone is having a rough day, do a little something nice to help the person out. Offer an extra pen or a sheet of paper. Help someone understand a tough concept. If you show compassion to whoever happens to be around, you’ll find you have real friends in many different groups, and your friendships will be bigger than any cliques.

Ending:

The writer sums up the problem and solution. Cliques cause a lot of pain for those stuck inside them as well as those excluded from them. If you can stand on your own feet and befriend others who are doing the same, you’ll be getting rid of a problem for yourself and for everyone around you.

WOC 221

Page 221

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Getting Ready to Write

Start by analyzing the prompt using the PAST strategy:

■ Purpose: Why am I writing? To persuade? To support a position?

■ Audience: Who will read my writing?

■ Subject: What topic should I write about?

■ Type: What form will my writing take?

Planning Your Writing

Choose a specific topic and decide how you want to write about it (your focus). Form a quick list identifying the facts, reasons, examples, or explanations you will use to support your focus.

Writing ■ Drafting Your Response

Beginning ■ The beginning of your response should introduce your topic and identify your opinion. (“Cliques may seem like friendship and belonging, but they really are the opposite, and students need to learn how to avoid them.”)

Middle ■ Explain the facts, examples, or reasons that support your opinion. Refer to your quick list for guidance, but also realize that you will need to add details to develop each main point from your quick list.

Ending ■ Restate your focus, summarize your main points, and/or provide a final idea about your topic.

Revising ■ and Editing ■

Save 5–10 minutes to revise and edit your response to the prompt. (Download a checklist.)

_____ Ideas Have I clearly stated the focus (opinion) of my essay and supported it with enough reasons and details?

_____ Organization Is my response organized and easy to follow?

_____ Voice Do I sound honest, sincere, and logical?

_____ Word Choice Have I used the best words to develop my response?

_____ Sentences Are my sentences smooth reading?

_____ Conventions Is my writing free of careless errors?