WOC 199

Page 199

Writing Argument Essays

Have you ever walked two or more dogs at once? They follow their noses and go every which way. They’ll pass on either side of a telephone pole and make you run into it.

So you have to be firm. You have to keep your destination in mind and gently guide the dogs to follow your route.

The same happens when you write an argument essay. When you offer an opinion, readers will have objections: “Wait, what about this . . . ?” You have to be ready to answer those objections and gently but firmly lead readers back to your point. Only logic and solid reasons can do that.

This chapter will equip you to lead readers from your opinion statement to your call to action—and avoid those telephone poles!

What’s Ahead

WOC 200

Page 200

Understanding Argument Writing

In an argument essay, you need to convince your reader to agree with you and perhaps take action. You need to understand your topic and reader so that you can build an argument that appeals to the person’s interests and needs.

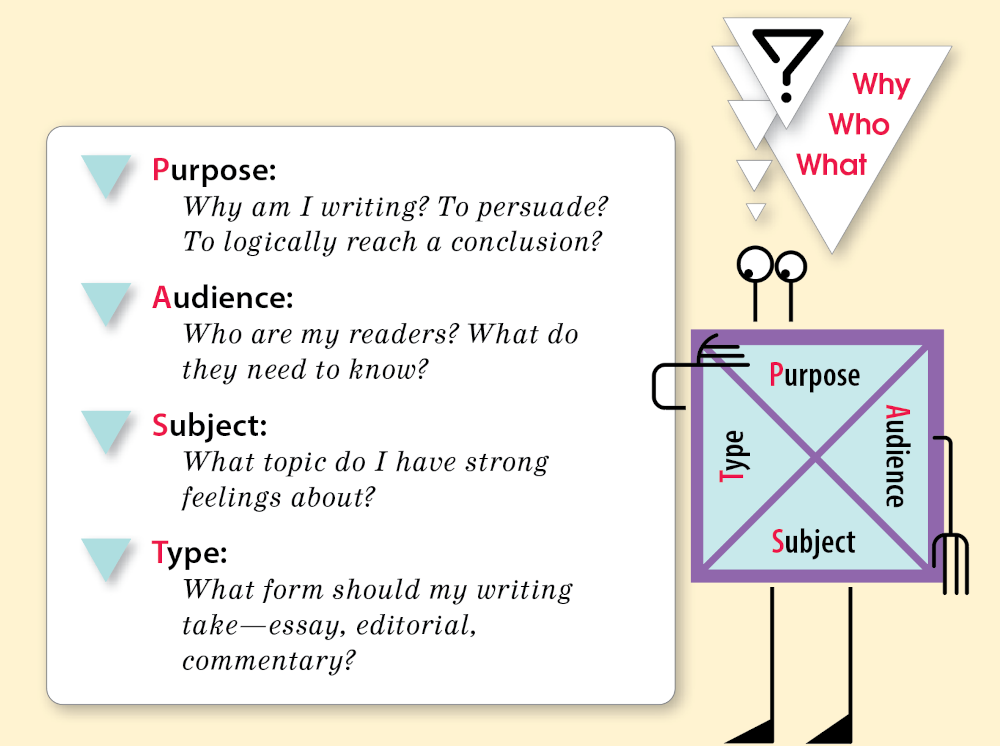

Consider the Writing Situation

Use the PAST strategy to analyze the situation for your argument writing. (See page 6.)

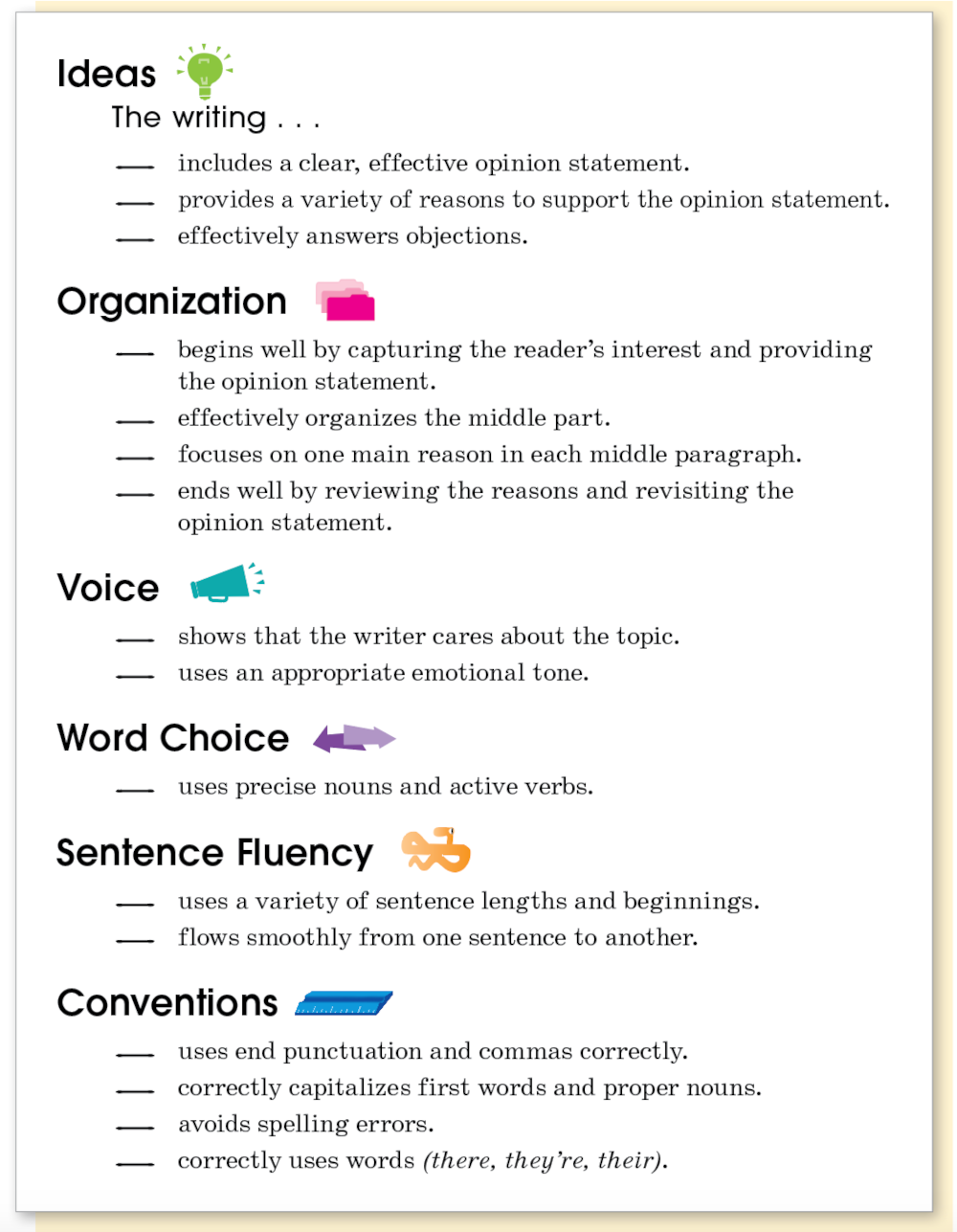

Link to the Traits

In prewriting, pay attention to ideas, organization, and voice.

Ideas ■

Select a topic that you feel strongly about. State your opinion clearly and provide effective supporting reasons.

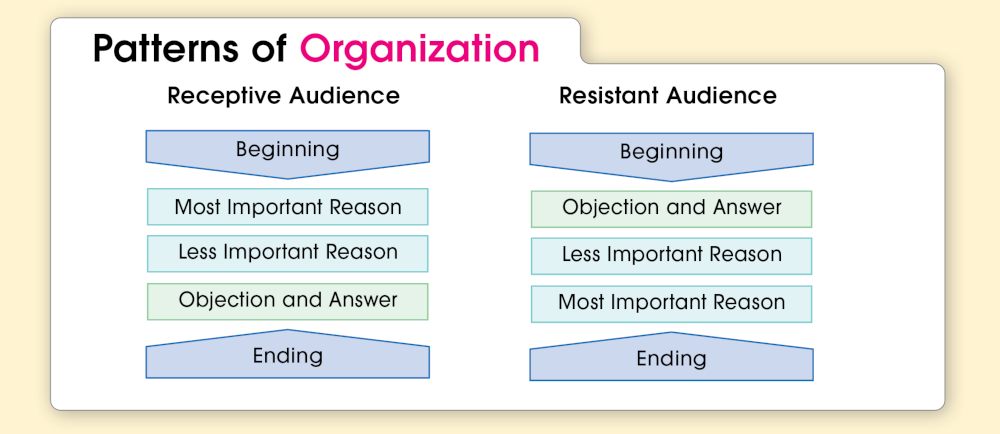

Organization ■

Organize to persuade. If your audience is receptive, place your strongest reason up front. If your audience is resistant, start by answering objections.

Voice ■

Use a voice that shows you care about the topic—but avoid sounding too emotional. Use a calm but caring tone.

WOC 201

Page 201

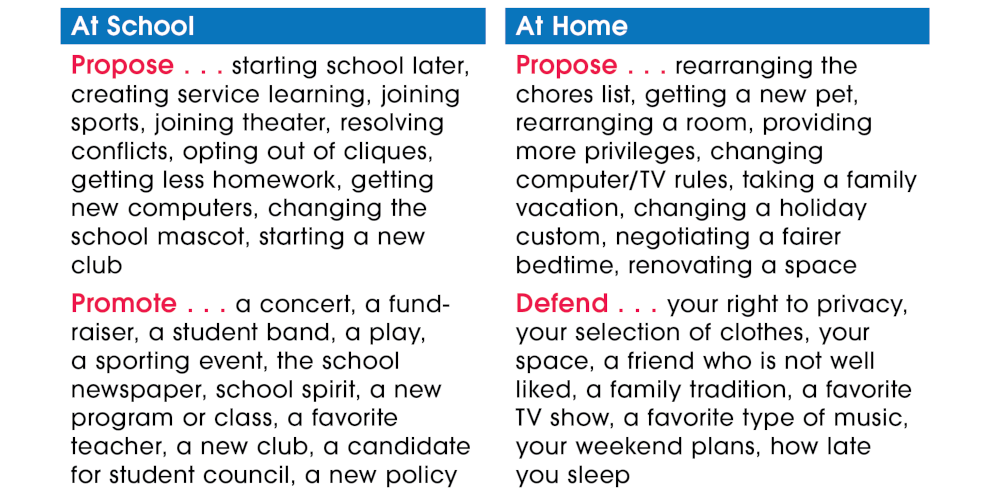

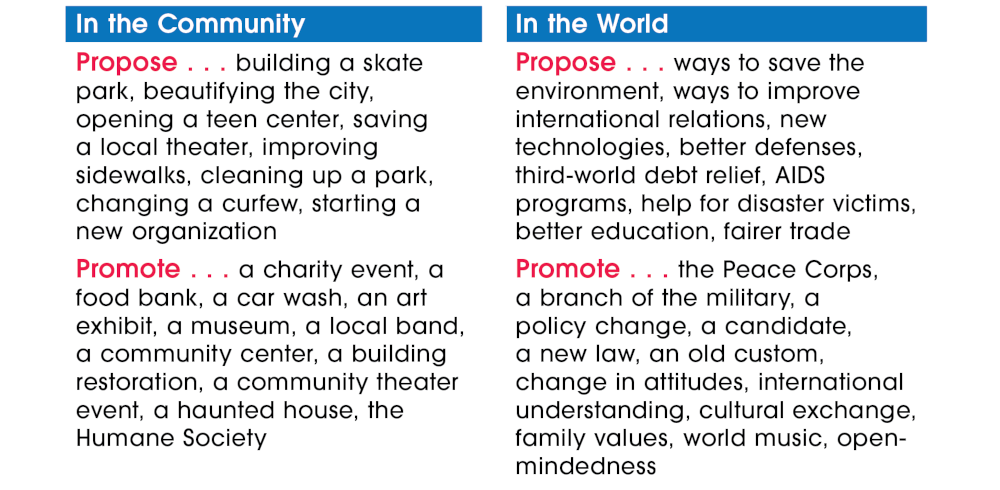

Argument Topic Ideas

The best argument (persuasive) writing begins with a topic that you have strong feelings about. Your job is to communicate your feelings about the topic and convince your reader to care about it just as much. There are great topics all around you—at school, at home, in your community, and out in the world. Here are a number of topics to consider for argument writing.

WOC 202

Page 202

Argument Essay

An argument essay defends or explains a thoughtful opinion with strong reasons. In the following essay, Emma Mirda argues for local voters to support a tax referendum for her school system.

Vote “Yes” on the CSD School Referendum

Beginning:

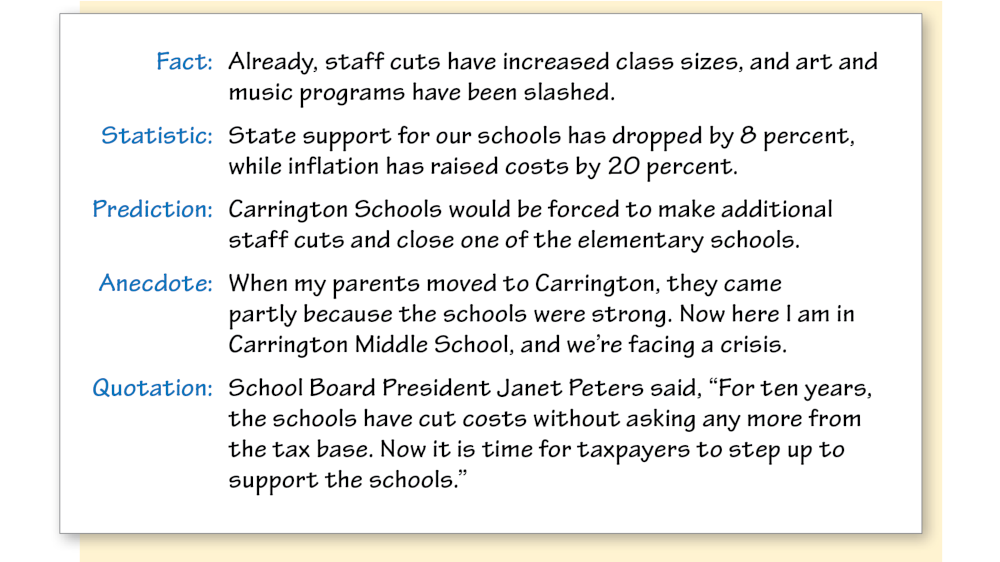

The essay starts with an anecdote and provides the opinion statement (underlined). When my parents moved to Carrington, they came partly because the schools were strong. Now here I am in Carrington Middle School, and we’re facing a crisis. This year, the school system is operating at a $2 million deficit. Already, staff cuts have increased class sizes, and art and music programs have been slashed (“CSD Referendum”). If the operating referendum fails, cuts will have to run much deeper. To save our schools, vote “yes” for the CSD referendum on February 20.

Middle:

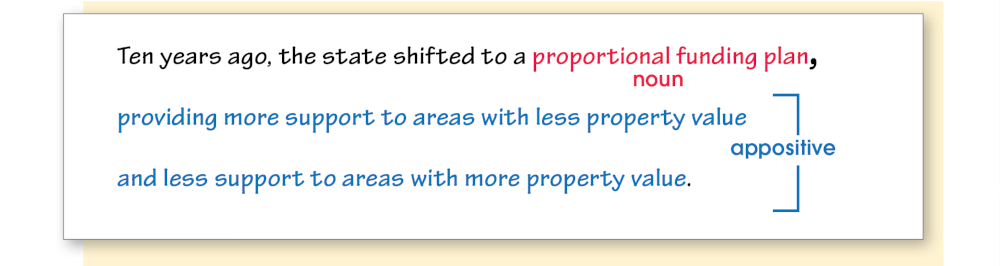

Middle paragraphs start with reader questions and provide answers. How did we get here? The school system used to receive 43 percent of revenues from local property tax, 50 percent from the state, and 7 percent from the federal government. Ten years ago, the state shifted to a proportional funding plan, providing more support to areas with less property value and less support to areas with more property value. During those years, state support for our schools has dropped by 8 percent, while inflation has raised costs by 20 percent. Carrington schools made cuts for nine of those years but now face a deep deficit in yearly operating costs (“Schools in Crisis”).

Facts, statistics, and predictions support the opinion statement. What does the referendum propose? The CSD operational referendum asks for a gradual increase in property taxes over the next four years to provide the school system with a functional budget. The increase would be just $75 per year for each $100,000 in property value. By the end of four years, a taxpayer with a $100,000 property would pay $300 more per year (“CSD Referendum”). That is less than a dollar per day to save the schools.

What would happen if the referendum failed? Carrington Schools would be forced to make additional staff cuts and close one of the elementary schools. These changes would cause class sizes to increase and would cause young students to be bussed farther from home to go to school. Increased class sizes will cause lower test scores, greater dropout rates, and teacher burnout. The current group of students will struggle, and young families will no longer be drawn to Carrington because of its school system.

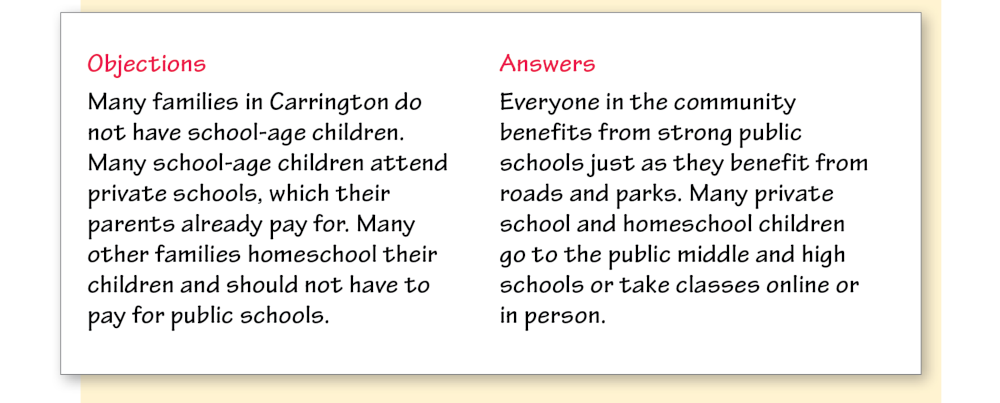

The next two paragraphs answer objections to the opinion. Some argue that people who don’t have children in the public schools should not have to pay for them. We have two Catholic and one Lutheran private school in the city, as well as many homeschoolers. However, many students who attend these private schools in elementary shift to Carrington Middle and High School later. Many homeschool students also take classes from the public schools, whether online or in person (“Public-Private Partners”). And strong public schools benefit the community, improving the lives of students and families and providing centers for sports and the arts. Schools are key not only to the future of their students, but also the future of our community.

Schools are infrastructure, like roads. You can argue that if you don’t drive you shouldn’t pay for roads, but your community needs roads. You can argue that you never go to the parks, so you shouldn’t have to pay for them. But Carrington needs parks. We also need strong schools.

Ending:

The writer makes a final plea and then calls readers to act. It’s time for us to step up to support our schools. The state has reduced its funding because it knows we have the ability to provide more support, while other communities don’t. We have the ability, but let’s see if we have the will. On February 20, vote “Yes” for the CSD operating referendum. If you aren’t old enough to vote, speak to the adults in your life who are and encourage them to vote “Yes.” It’s time for us to support Carrington Schools.

Note: The works-cited page is not shown.

WOC 204

Page 204

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Selecting a Topic

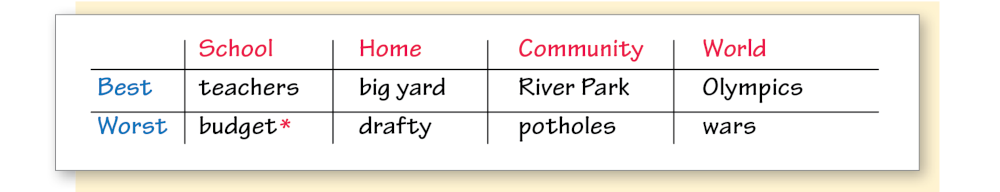

The first step in writing a persuasive essay is to find a topic you feel strongly about. Emma came up with an idea by listing the best and worst things in her school, home, community, and world. Then she chose a “worst thing” she wanted to address. (Download a best-and-worst chart template.)

Best-Worst Chart

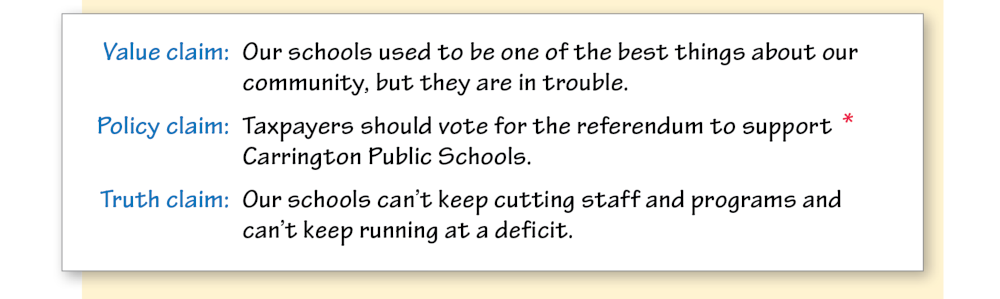

Forming an Opinion

After selecting a topic, you need to form your opinion about it. Your opinion can be a value claim (the goodness or badness of something), a policy claim (what should be done), or a truth claim (a hypothesis one hopes to prove). Emma wrote each type of claim and then chose one to be her opinion statement (see asterisk).

Helpful Hint

If you don’t know enough about your topic, research it before forming your final opinion. Also be open to changing your mind as you research. The best opinions are informed opinions that are backed by accurate and complete information and facts.

WOC 205

Page 205

Gathering Reasons

Once you have a strong opinion statement, you need to gather a variety of reasons to support it. Emma gathered the following reasons.

Answering Objections

Next, you need to consider opposing points of view. By mentioning an objection or two and then providing answers to the objections (countering them), you actually strengthen your argument. Emma listed objections to her opinion and then wrote answers.

WOC 206

Page 206

Writing ■ Developing the First Draft

Now you are ready to write your argument essay. Each part of the essay has a different job to do.

Beginning ■ In the beginning, you need to get your reader’s attention and lead up to your opinion statement. Here are some strategies for getting your reader’s attention:

- Connect with the reader’s concerns.

The budgetary alarm bells are ringing for our public schools.

- Ask a shocking question.

Which of our elementary schools should we close?

- Begin with an anecdote.

When my parents moved to Carrington, they came partly because the schools were strong. Now here I am in Carrington Middle School, and we’re facing a crisis.

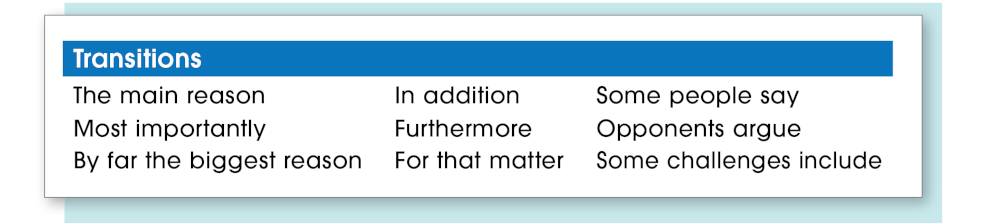

Middle ■ The middle part of your essay should present your reasons using order of importance. If your audience is receptive to your message, start with your strongest reason. If your audience is resistant, start by answering objections. Transition words and phrases can help you signal your organizational pattern. Here are some suggestions.

Ending ■ Develop a strong ending. Here are some strategies:

- Restate your position.

It’s time for us to step up to support our schools.

- Sum up your argument.

The state has reduced its funding because it knows we have the ability to provide more support, while other communities don’t. We have the ability, but let’s see if we have the will.

- Call the reader to take action.

On February 20, vote “Yes” for the CSD operating referendum. If you aren’t old enough to vote, speak to the adults in your life who are and encourage them to vote “Yes.”

It’s time for us to step up to support our schools.

The state has reduced its funding because it knows we have the ability to provide more support, while other communities don’t. We have the ability, but let’s see if we have the will.

On February 20, vote “Yes” for the CSD operating referendum. If you aren’t old enough to vote, speak to the adults in your life who are and encourage them to vote “Yes.”

WOC 207

Page 207

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving the Writing

When you revise your persuasive essay, you add, cut, move, and rework ideas to make your writing stronger. Here’s a quick checklist to guide your revising.

_____ Ideas Is my opinion clear and supported by strong reasons?

_____ Organization Do my reasons appear in the most persuasive order?

_____ Voice Do I use a persuasive voice? (See below.)

_____ Word Choice Do I use strong nouns and active verbs?

_____ Sentences Do my sentences read smoothly?

_____ Conventions Have I carefully checked punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and grammar?

A Closer Look at Revising ■ Persuasive Voice

Your best persuasive voice will connect to your topic and audience in the following ways:

- Knowledge of the topic (Use a variety of details.)

- Concern about the topic (Use a warm tone.)

- Respect for the reader (Use appropriate language.)

If your voice is not persuasive, decide whether you need to show more knowledge, more concern, or more respect. Then revise your voice by following the advice listed in parentheses above.

A Closer Look at Editing ■ Punctuation

Commas are used to set off an appositive—a word, phrase, or clause that follows a noun and renames, explains, or describes it.

If you can remove the appositive from the sentence without changing the meaning, set off the appositive with a comma (or two, if it interrupts the sentence). If the appositive can’t be removed, don’t set it apart from the sentence.