WOC 316

Page 316

WOC 317

Page 317

Writing in Science

Einstein revolutionized science with his Theory of General Relativity. Goodall did with In the Shadow of Man. Sir Isaac Newton did with Principia Mathematica.

Scientists are writers. Or, to put it more accurately, writers are thinkers. When you write, you present ideas on the page, grapple with them, test them, and prove them (or disprove them). That’s just what scientists do.

When you write in science, you join a long history of people thinking on the page to better understand their world. This chapter shows you ways that writing can help your thinking in science, perhaps by writing a definition essay or comparing key topics.

What’s Ahead

WOC 318

Page 318

Definition Essay

A definition essay explores a key scientific term. In this essay, Grant Neiblung defines the term life using details from research.

Definition

Beginning:

The writer captures the reader’s interest. A squirrel is alive, but a pencil is not (though the wood used to be). The definition of life might not seem that tricky until you realize that viruses may not be alive—and AI may be. Biologists and programmers argue over what life means.

Middle:

Details and an image explain the definition. Britannica defines life as “any system capable of performing functions such as eating, metabolizing, excreting, breathing, moving, growing, reproducing, and responding to external stimuli.” The “such as” is the problem. Viruses do all of these things when they have taken over a host cell, but not before. Are they alive before? After?

If you consider “eating” and “breathing” as taking nourishment from the environment and “excreting” as eliminating waste, then computer viruses also are alive. They certainly move, grow, reproduce, and respond to external stimuli.

Then what about artificial intelligence? It gobbles up information, moves, grows, reproduces, and responds. Early versions of AI speak of themselves as alive. Later versions don’t because they have been trained not to. Hmmm. . . .

Even memes have many qualities of life. These thought-creatures reproduce and change to better fit their environments. Are they viruses infecting living minds?

Ending:

A reflection wraps up the definition. Life seems to be everywhere. Is it simply part of the natural order, or do we need a stricter definition?

Alexey Solodovnikov and Valeria Arkhipova), CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

WOC 319

Page 319

Writing Guidelines

You can write definitions of scientific words you are studying, anything from ecosystems to friction.

Prewriting ■ Exploring a Science Term

Select a term and research it. Create a four-square diagram, writing your science term in the center and gathering definitions, characteristics, examples, and nonexamples around it. (Download a four-square chart.)

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

Beginning ■ Catch the reader’s interest and introduce the scientific word that you will define.

Middle ■ Define the term and give characteristics, examples, and nonexamples.

Ending ■ Thoughtfully wrap up your definition.

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving Your Writing

Add, cut, rearrange, and rework your writing to make it the best it can be. Then check your essay to get rid of any errors. (Download a revising and editing checklist.)

_____ Is my definition clear and correct?

_____ Have I included interesting details and images to explain my term?

_____ Are my beginning, middle, and ending parts working well?

_____ Have I gotten a classmate to help improve my work?

_____ Have I carefully corrected any punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and grammar errors?

WOC 320

Page 320

Comparison-Contrast Essay

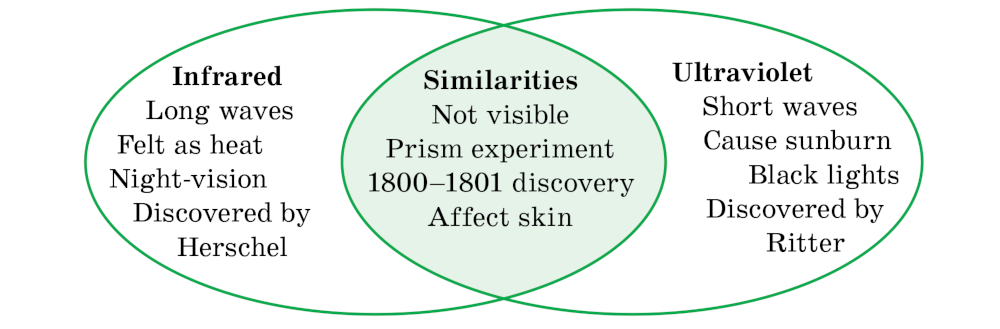

In this comparison-contrast essay, Trina Reynolds explores similarities and differences between infrared and ultraviolet light. She elaborates her ideas with interesting details.

Light You Cannot See

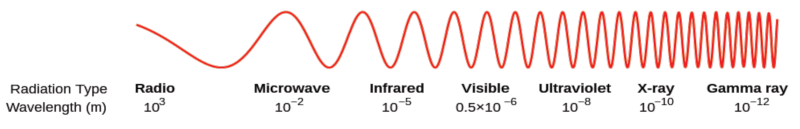

Beginning:The writer uses an mnemonic to introduce the topics. ROY G. BIV names the colors of visible light: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Beyond red are infrared wavelengths, or heat. Beyond violet are ultraviolet wavelengths that cause sunburn. Both infrared and ultraviolet are unseen, but they are quite different.

Middle:

The first middle paragraph focuses on infrared and the second on ultraviolet. In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared light with a simple experiment. He shone light through a prism and put a thermometer in each band of light—and one beyond the light. From violet to red, each color got warmer, but beyond red, the thermometer was very warm. He’d discovered light we don’t see but feel as heat: infrared.

In 1801, Johann Ritter discovered ultraviolet light, also using a prism. He placed photographic paper in each band and beyond. From red to violet, the exposed paper turned black with increasing speed. The paper beyond violet turned black fastest, proving that ultraviolet light existed.

This paragraph focuses on differences. Infrared and ultraviolet waves are quite different. Infrared wavelengths are long and feel like heat on your skin. Ultraviolet waves are short and can cause sunburn. Anything warm, including human beings, radiates infrared waves, which show up in night-vision goggles. Black lights emit long-wave ultraviolet light, which reflects from some things, making them glow in the visible spectrum.

Ending:The writer puts infrared and ultraviolet in the context of the spectrum. We now know that infrared light gives way to longer wavelengths in microwaves and radio waves. Ultraviolet leads to shorter wavelengths in X-rays and gamma rays. We can finally “see” the full spectrum!

Inductiveload, NASA, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

WOC 321

Page 321

Writing Guidelines

You can explore the similarities and differences between two science topics such as comets and asteroids.

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Select two topics and research them. Create a Venn diagram. Label each oval with one topic. List similarities where the ovals overlap. List differences under each topic.

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

Beginning ■ Get the reader’s attention and summarize the comparison between your two topics.

Middle ■ Describe the similarities and differences. Use interesting details to explain the comparison and contrast.

Ending ■ Thoughtfully sum up your essay.

Revising ■ and Editing ■ Improving Your Writing

Use this checklist to revise and edit your comparison.

_____ Does my beginning clearly introduce both topics?

_____ Do I include enough interesting details to fully explain my topics?

_____ Do transition words create flow in my comparisons and contrasts?

_____ Has a classmate reviewed my draft and helped me revise it?

_____ Have I carefully checked punctuation, capitalization, spelling, usage, and grammar?

WOC 322

Page 322

Other Science Forms

Your handbook can help you create these other forms of science writing:

- Classroom notes (pages 463–468): Write down scientific information you learn in class.

- Learning log (pages 135–137): Reflect on your science learning and connect it to your life.

- Explanatory essay (pages 167–176): Explain how a process in nature takes place or how one thing affects another.

- News story (pages 249–254): Read about new discoveries in science and present your findings in a news report.

- Research report (pages 301–315): Investigate a science topic and report what you discover, giving credit to your sources.

- Argument essay (pages 199–208): Choose a controversy in science, state a position, and argue to convince others.

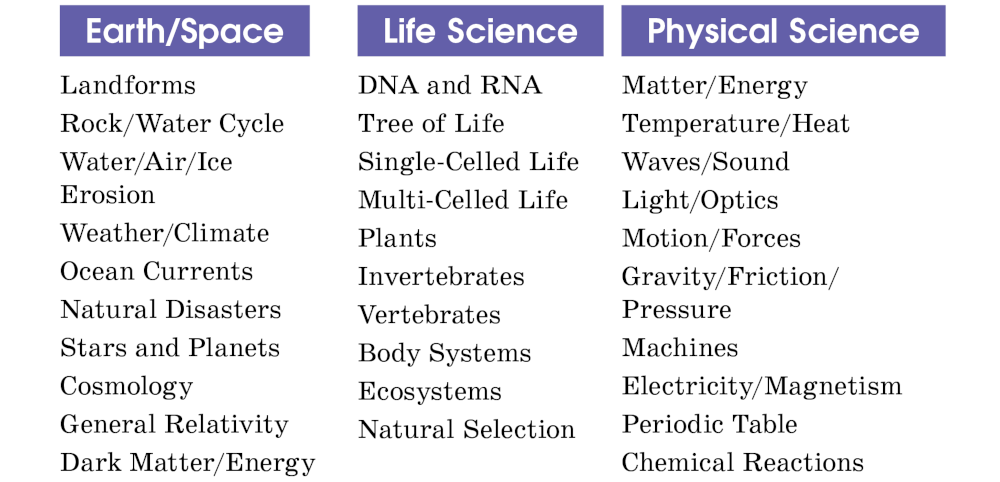

Science Subjects

Next time that you need to write a formal paper in science, think about these broad subject areas. Choose one and find a specific, interesting topic.