WOC 277

Page 277

Writing Poetry

What do you need to befriend a tree?

An open heart is a good start,

a sunny Saturday to laze away

beneath a crowd of leaves

chanting in the breeze,

eyes splashed with green,

fingers gripping boughs,

the sweet scent of living.

Time, really.

Time is all you need.

A poem is just as easy to befriend, and

it takes the same things—an open heart and

time. This chapter will teach you how to read

and befriend poems, and how to write your

own amazing poetry!

What’s Ahead

WOC 278

Page 278

What Is Poetry?

The poet Marianne Moore defines poetry as “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.” Good poetry is always creative and, at times, a bit playful. An effective poem takes us away to an “imaginary garden,” yet it often springs from a real experience—one of the many “toads” hopping in and out of our daily lives.

What makes poetry different from prose (the regular writing you do)? Here are some of the differences that make poetry so special.

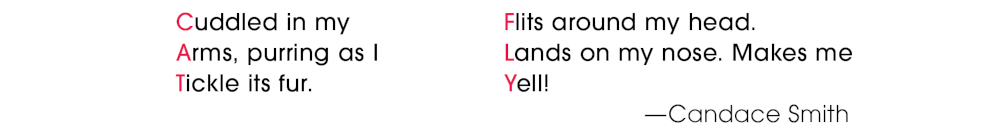

■ Poetry looks different from prose.

Poems are written in lines and stanzas (groups of lines), leaving a fair amount of white space on the page. Notice the look of this eight-line poem by a great American humorist:

■ Poetry sounds different.

Poets pay special attention to the sounds in their writing. Here are some of the techniques that make poems pleasing to the ear.

- Repeat words: It does not cluck / A cluck it lacks.

- Rhyme words: It is specially fond / Of a puddle or pond.

- Repeat vowel sounds: It bottoms ups.

- Repeat consonant sounds: Of a puddle or pond.

- Use words that sound like what they mean: It quacks.

WOC 279

Page 279

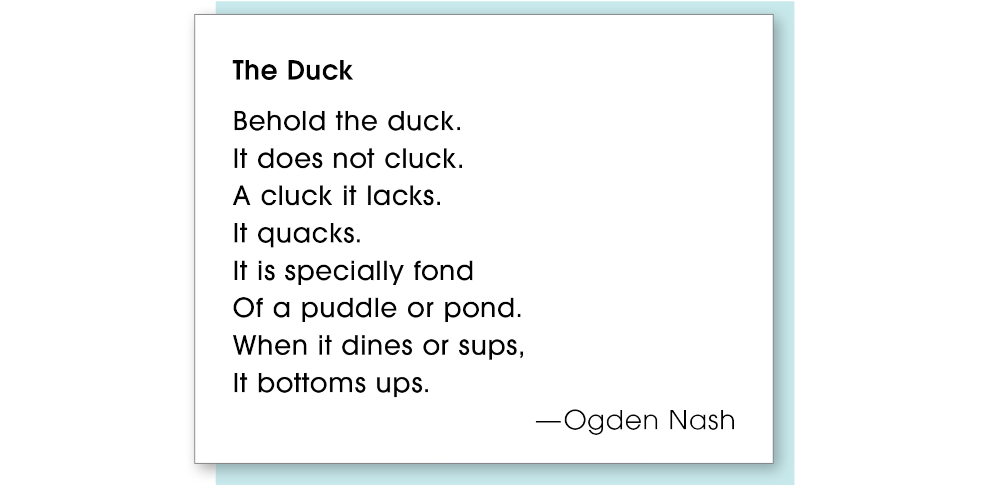

■ Poetry speaks to the heart.

Poetry asks you to feel something (that’s the heart part), not just think about it. In the following example, you can tell how the poet feels about his pets:

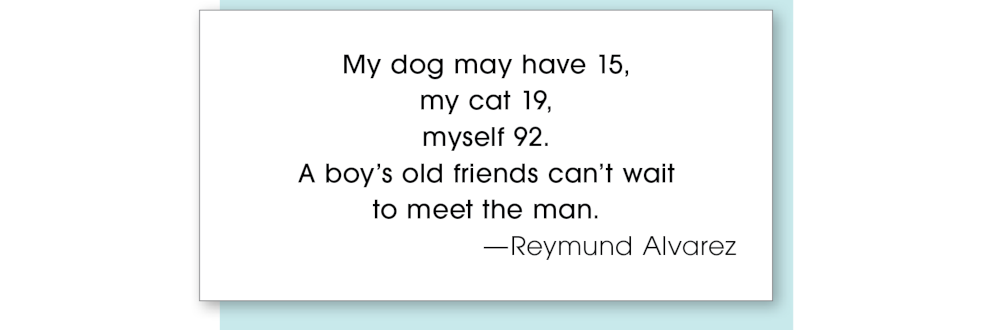

■ Poetry speaks to the senses.

Poets create word pictures that build an image in your mind. Notice how the following examples appeal to different senses.

WOC 280

Page 280

Reading and Appreciating Poetry

These days, most words are disposable. You read them once and toss them aside. Poetry bears re-reading. You hang out with a poem the same way that you hang out with a friend, getting to know it well. Follow these tips to get the most out of poetry.

Read Carefully

- Read the poem once through to get a general sense of how it flows and what it says.

- Read the poem a second time, slowly and carefully. Enjoy each word and phrase.

- On your third pass, read aloud so that you can hear the many sounds within it.

- On your fourth pass, let yourself sense the poem—sights, sounds, textures, tastes, and smells.

- Reflect on the poem and how it makes you feel. Let it connect to your own memories, hopes, and dreams.

- Share the poem with your friends and discuss it afterward. Their insights will help you enjoy the poem even more.

Apply Your Knowledge

- Think about the techniques used by the poet.

- Pay attention to the poem’s structure. How does it look on the page? Does the poem have a unique shape?

- Look at the line breaks. How do they shape the poem?

- What rhythm does the poem have? Is it regular or free-flowing?

- What words rhyme? What words start with the same letter?

- What words sound like the noise they describe?

WOC 281

Page 281

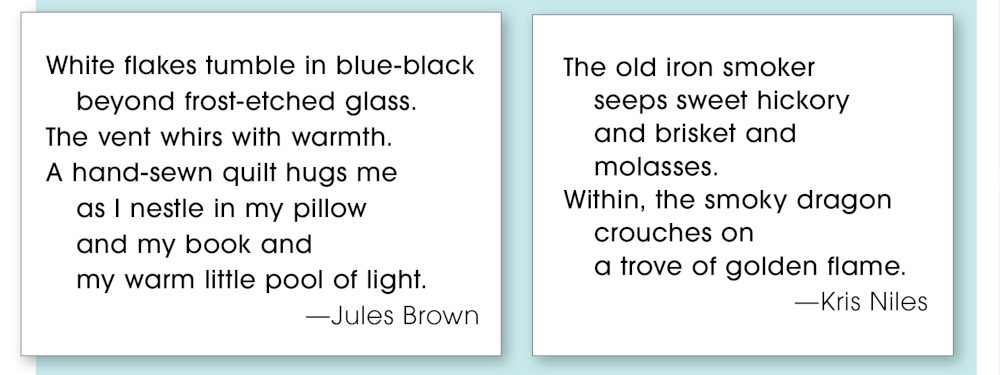

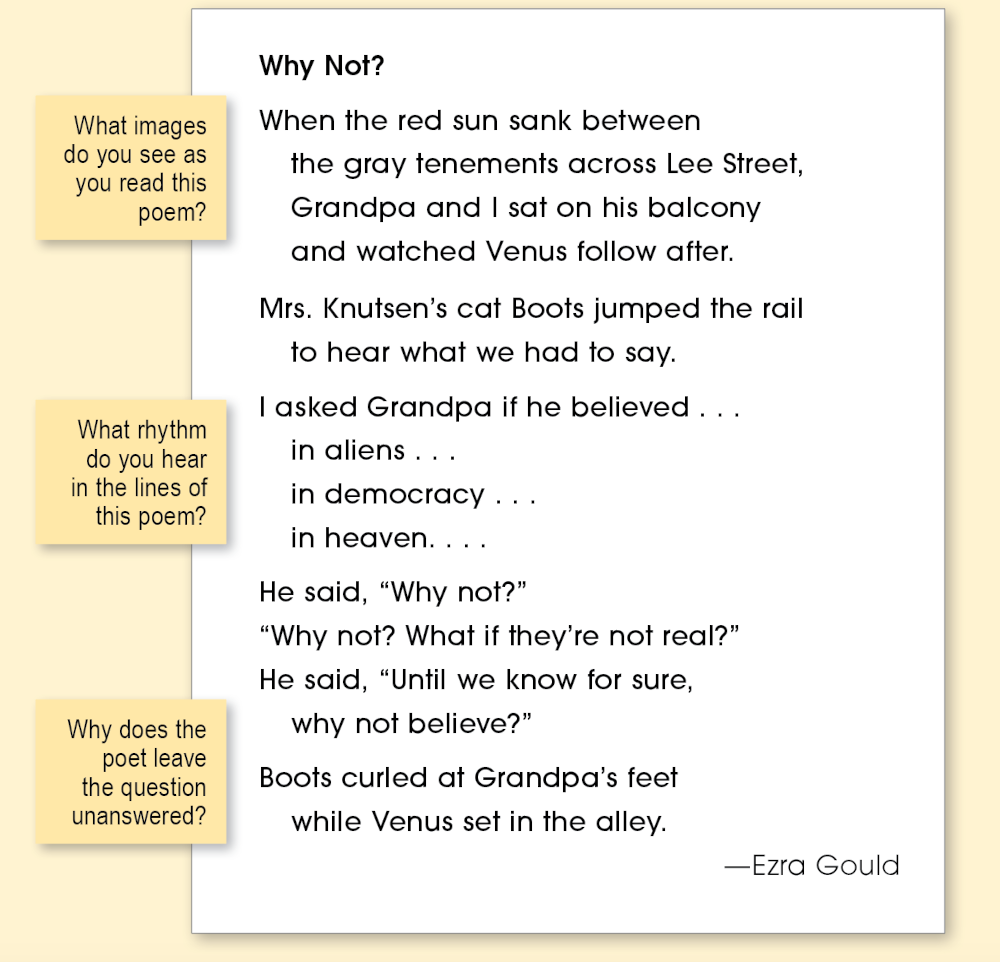

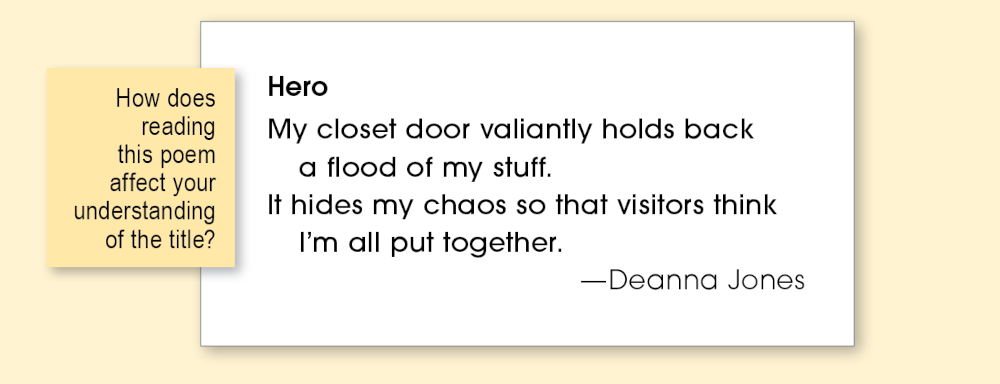

Poems

Read and enjoy the following two student poems. (Remember to follow the tips and strategies listed on the previous page.)

WOC 282

Page 282

Writing Guidelines

Writing poetry is a lot of fun. It allows you to use language in special ways. It also lets you share an experience or a feeling in ways that will stir your reader’s emotions.

Writing poetry is also work. Good poets write and rewrite their poems many times to get the best effect from the fewest words. The guidelines that follow will help you write a free-verse poem, a poem that does not require regular rhythm or rhyme.

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Choose a topic you really care about.

- Remember an important time or event in your life: a special trip, the first day at a new school, a special gathering you attended.

- Look at the world around you: the sparkle of summer sun on a pond, a stuffed animal, loose litter cluttering a yard.

- Describe something you like or dislike: a tasty food, a favorite sweater, a case of the flu, a muggy day.

- Think of a favorite person: a grandparent, a historical figure, a sports hero, your best friend.

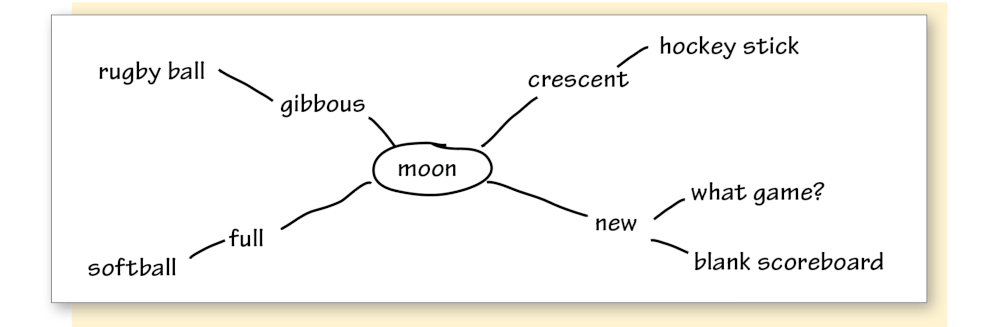

Gathering Details

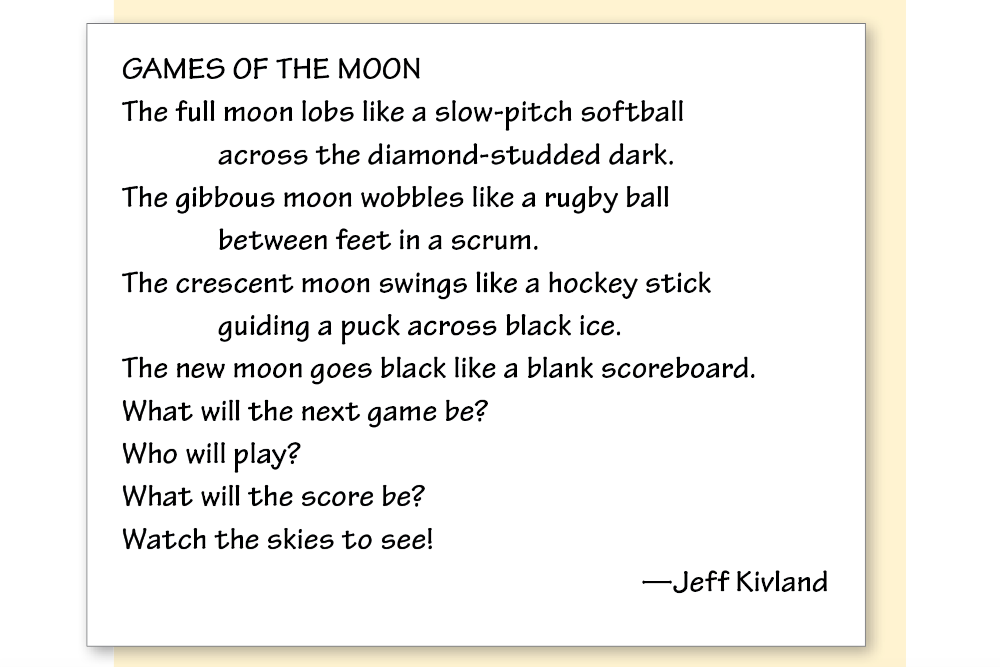

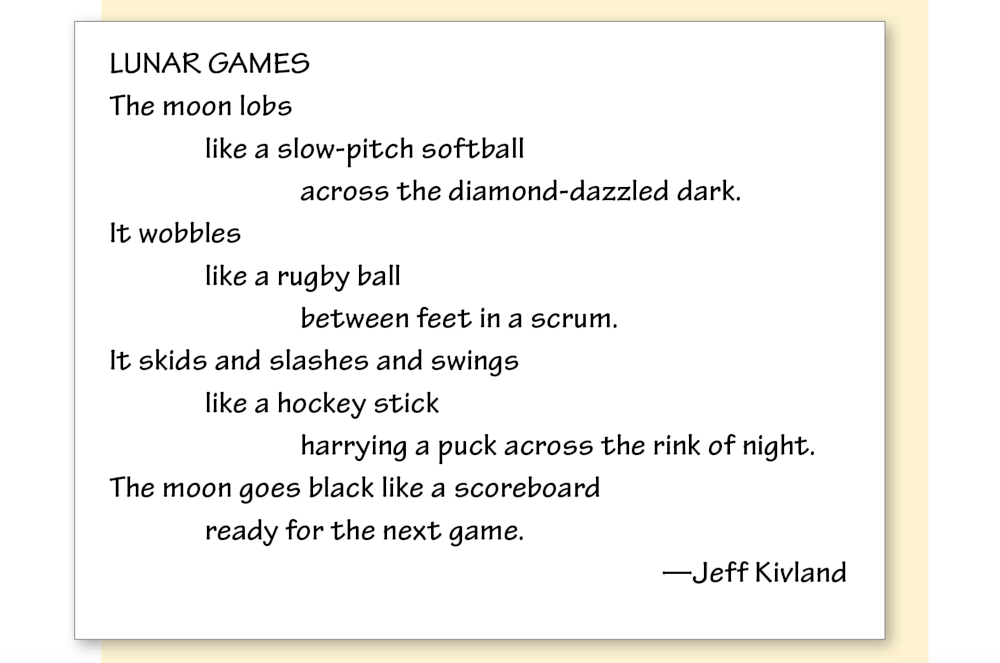

Begin collecting ideas about your subject. Student writer Jeff Kivland decided to write about the moon, focusing on its phases. Here is his initial cluster of ideas.

After you have collected enough details, look for a powerful idea or image as a focus. Jeff focused on games.

WOC 283

Page 283

Writing ■ Creating the First Draft

Don’t worry about writing the perfect poem in your first draft; just write freely until you’ve said all that you need to say about your subject. Remember the senses—sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures related to the topic. Shape your poem in whatever way feels right. You can reshape it as you work with it.

Revising ■ Improving Your Writing

After you complete your first draft, carefully review your poem. Use the following checklist as your reviewing guide:

_____ Ideas Are my ideas complete? Do they convey the meaning and feeling I want to convey?

_____ Organization Do the line breaks work well? Does the form add to the poem’s effect?

_____ Voice Does my voice fit the topic, the meaning, and the feeling of the poem?

_____ Word Choice Have I carefully selected each word for sound and meaning?

_____ Sentences Does my poem flow as I intend?

WOC 284

Page 284

Editing ■ Checking for Style and Accuracy

Check your revised poem for punctuation, capitalization, spelling, and grammar errors. Ask someone else to check your work for errors as well. Then write a correct final copy of your poem. Proofread this copy before sharing it.

Helpful Hint

In a free-verse poem, you do not have to capitalize the first word in each line. The choice is yours. Use end punctuation marks or other punctuation as you would in regular prose. Or don’t use punctuation at all if you don’t feel it is necessary. (See the poem below.)

Free-Verse Poem

Jeff Kivland made many changes to his poem: title, images, line breaks, and word choice. Notice how he removed the moon cycles, inviting readers to infer them, which creates mystery.

WOC 285

Page 285

Publishing ■

Poems can be shared in many creative ways. For example, poetry and art complement each other extremely well. Poetry can also be performed. All you need is a bit of preparation and a willing audience.

Poetry and Art

- Poster: Present your poem, together with an illustration or a drawing, on a piece of poster board.

- Bookmark: Write your poem on a colorful piece of paper cut to bookmark size and shape. Decorate the bookmark in any way you wish.

- Greeting Card: Create a greeting card. Write your poem on the front and add a personal message inside. Or write your poem inside and illustrate the front of the card.

Poetry and Drama

- Oral Reading: Reciting poetry aloud is an effective way to share its rhythm. Consider using background music for your performance. Be sure to practice your delivery until it is smooth and dramatic before you read to your audience.

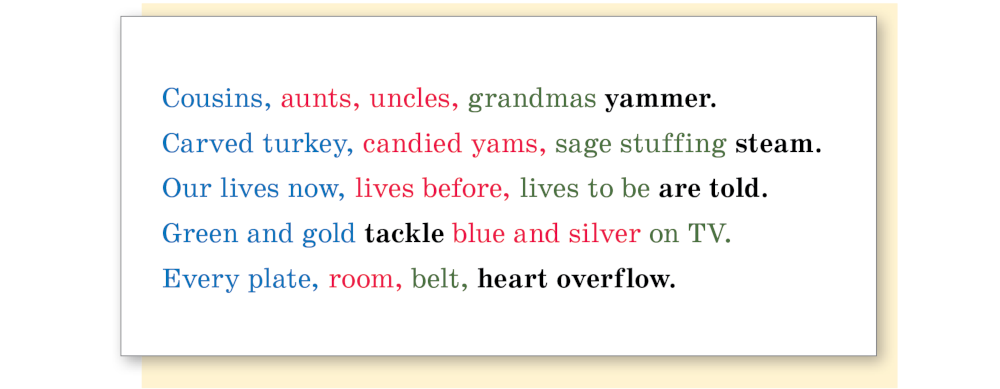

- Perform a Poem: It can be fun to perform a poem with different people reciting different sections. To get started, script the poem to show who should read the different lines. A script for Robin Whitman’s poem is provided below.

Script

Three voices are needed. The poem is color-coded to indicate voice 1, voice 2, voice 3, and all together.

WOC 286

Page 286

Traditional Techniques of Poetry

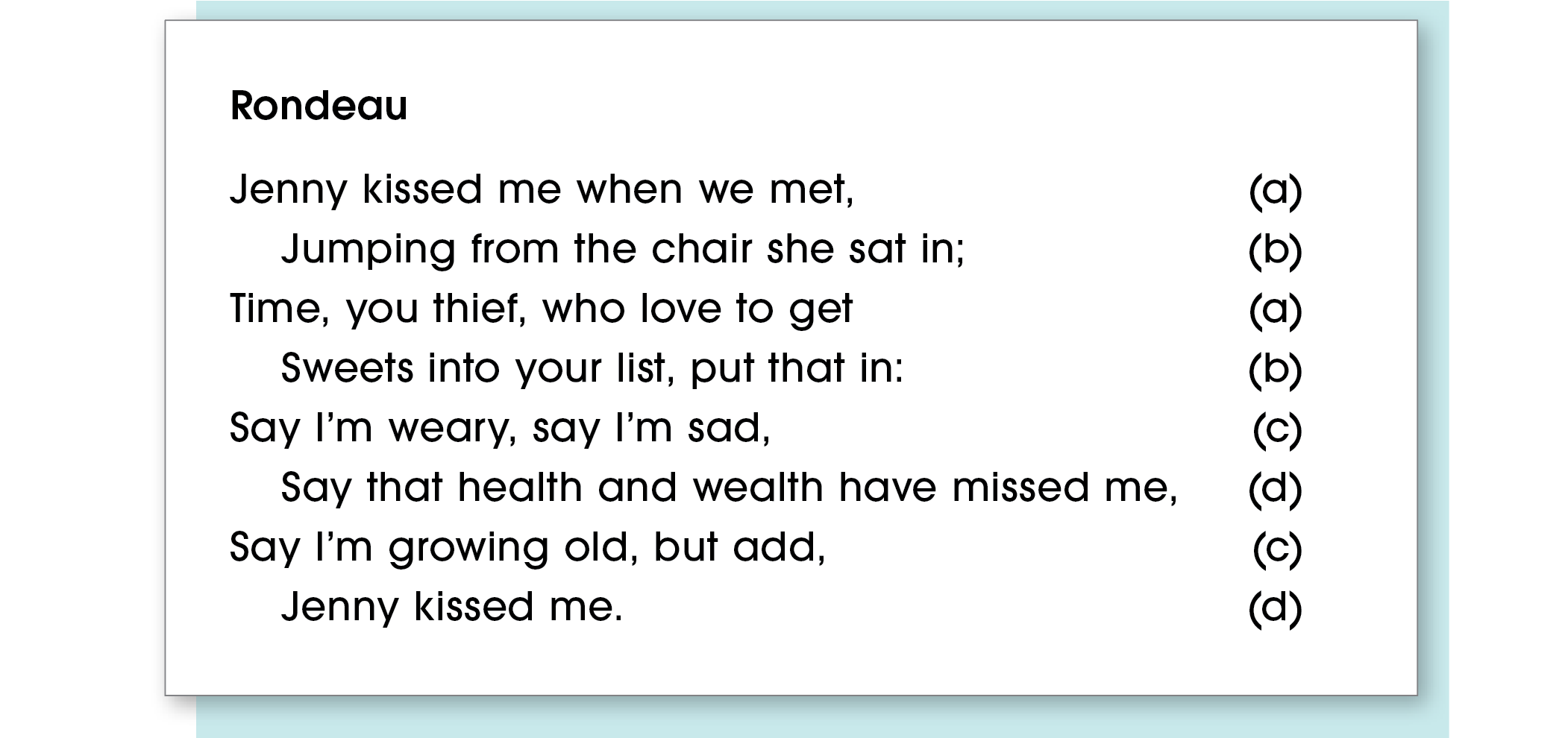

Most traditional poems follow exact patterns of rhyme and rhythm. Consider this famous traditional poem by Leigh Hunt:

Rhyme and Meter

In most traditional poetry, the rhyme is organized in patterns called rhyme schemes. (See the letters in parentheses above.)

Meter is the rhythm, or pattern of accented and unaccented syllables, in the lines of a poem. In the poem above, every other syllable is accented. (Jenny kissed me when we met.) This pattern of accented and unaccented syllables creates the poem’s meter. (See foot and verse for more information on meter.)

Other Poetry Techniques

Alliteration ■ The repeating of beginning consonant sounds.

Strong strings connect us.

Strained strings remind us

we are woven together as one.

Assonance ■ The repetition of vowel sounds, as in the following lines from “The Hayloft” by Robert Lewis Stevenson.

Till the shining scythes went far and wide

And cut it down to dry.

WOC 287

Page 287

Consonance ■ The repetition of consonant sounds anywhere within words, not just at the beginning.

A friend offends without offense.

A foe offends with kind pretense.

End Rhyme ■ The rhyming of words at the ends of lines, as in the following lines.

The sigh of cars upon wet streets,

Arrives, retreats,

Again repeats.

Foot ■ One unit of meter. There are five basic feet:

- Iambic: An unaccented syllable followed by an accented one (repeat)

- Trochaic: An accented syllable followed by an unaccented (older)

- Anapestic: Two unaccented syllables before one accented (interrupt)

- Dactylic: An accented syllable followed by two unaccented (openly)

- Spondaic: Two accented syllables (heartbreak)

Internal Rhyme ■ The rhyming of words within one line of poetry.

Jack Sprat could eat no fat (or) Peter Peter pumpkin eater.

Onomatopoeia ■ The use of a word whose sound makes you think of its meaning, as in buzz, gush, roar, swish, yodel, zing, or zip.

Quatrain ■ A four-line stanza. Common rhyme schemes in quatrains are aabb, aaba, and abab.

Repetition ■ The repeating of a word or phrase to add rhythm or to focus on an idea, as in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.”

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

as of someone gently rapping

rapping at my chamber door—

Stanza ■ A division in a poem named for the number of lines it contains. Below are the most common stanzas.

Couplet: two-line stanza

Triplet: three-line stanza

Quatrain: four-line stanza

Sestet: six-line stanza

Septet: seven-line stanza

Octave: eight-line stanza

Verse ■ A name for a line of poetry written in meter. Verse is named according to the number of “feet” per line. Here are eight types:

Monometer: one foot

Dimeter: two feet

Trimeter: three feet

Tetrameter: four feet

Pentameter: five feet

Hexameter: six feet

Heptameter: seven feet

Octometer: eight feet

WOC 288

Page 288

Traditional Forms of Poetry

Poetry has been around for centuries, beginning with bards and messengers who used poems to pass along news, songs, and stories. Today, we find poetry in songs, on greeting cards, in reading anthologies, and so on. Here are some traditional forms of poetry.

Ballad ■ A ballad is a poem that tells a story. Ballads are usually written in four-line stanzas called quatrains. Often, the first and third lines have four accented syllables; the second and fourth have three. (See quatrain for possible rhyme schemes.) Here is a quatrain from “The Enchanted Shirt” by John Hay.

The King was sick. His cheek was red

And his eye was clear and bright;

He ate and drank with a kingly zest,

And peacefully snored at night.

Blank Verse ■ Blank verse is unrhymed poetry with meter. The lines in blank verse are 10 syllables in length. Every other syllable, beginning with the second syllable, is accented. (Note: Not every line will fit this description exactly.) Consider these first three lines from “Andrea Del Sarto” by Robert Browning.

But do not let us quarrel any more,

No, my Lucrezia; bear with me for once:

Sit down and all shall happen as you wish.

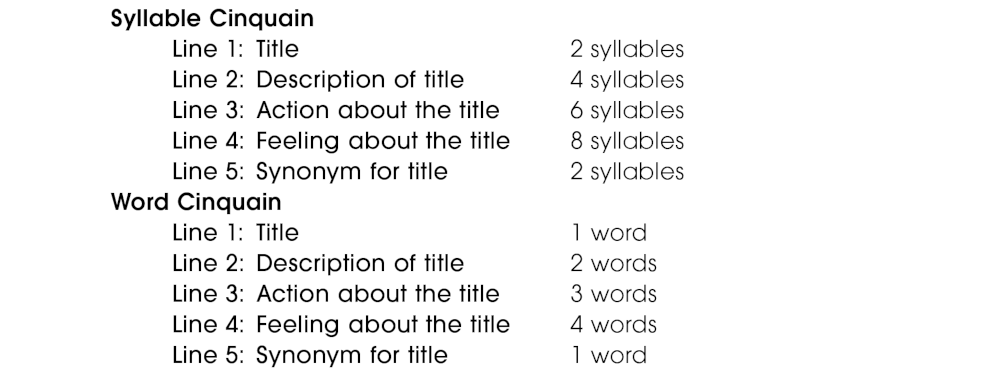

Cinquain ■ Cinquain poems are five lines in length. There are syllable and word cinquain poems.

Couplet ■ A couplet is two lines of verse that usually rhyme and state one complete idea. (See stanza.)

WOC 289

Page 289

Elegy ■ An elegy is a poem that states a poet’s sadness about the death of an important person. In “O Captain, My Captain,” Walt Whitman writes about the death of Abraham Lincoln.

Epic ■ An epic is a long story poem that describes the adventures of a hero. “The Odyssey” by Homer is a famous epic about the Greek hero Odysseus.

Free Verse ■ Free verse is poetry that does not require meter (regular rhythm) or a rhyme scheme.

Haiku ■ Haiku is a type of Japanese poetry that presents a picture of nature. A haiku poem is three lines in length. The first line is five syllables; the second, seven; and the third, five.

I shovel the snow

from my walk and from the perch

of my birdfeeder

—Rob King

Limerick ■ A limerick is a humorous verse of five lines. Lines one, two, and five rhyme, as do lines three and four. Lines one, two, and five have three stressed syllables; lines three and four have two. (Download a limerick-writing activity.)

There once was a panda named Lu, (a)

Who always ate crunchy bamboo. (a)

He ate all day long, (b)

Till he looked like King Kong. (b)

Now the zoo doesn’t know what to do. (a)

—Sarah Diot

Lyric ■ A lyric is a short poem that expresses personal feeling.

My Heart Leaps Up When I Behold (first 5 lines)

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky;

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old.

—William Wordsworth

Ode ■ An ode is a long lyric that is deep in feeling and rich in poetic devices. “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is a famous ode by John Keats.

Sonnet ■ A sonnet is a 14-line poem that states a poet’s personal feelings. The Shakespearean sonnet follows the abab/cdcd/efef/gg rhyme scheme and an iambic pentameter format. (See foot and verse.)

WOC 290

Page 290

Other Forms of Poetry

Don’t be afraid to try something new the next time you sit down to write a poem. The forms of poetry that follow will help you get started.

Alphabet Poetry ■ A form of poetry that states a creative or humorous idea using part of the alphabet.

We

X-ray

Young

Zoo

Animals

Best to

Catch

Disease

—Zachariah Surrency

Clerihew Poetry ■ A form of humorous or light verse created by Edmund Clerihew Bentley. A clerihew poem consists of two rhyming couplets. The name of some well-known person creates one of the rhymes.

Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Brooded intently

On many a foible

He thus made enjoyable.

—Colin Burke

Concrete Poetry ■ A form of poetry in which the shape or design helps express the meaning or feeling of the poem.

Contrast Couplet ■ A couplet in which the first line includes two words that are opposites. The second line makes a comment about the first.

Some hours are too short, and some are too long.

I wonder who made the clocks all wrong.

—L. Winfred Smith

Definition Poetry ■ Poetry that defines a word or an idea creatively.

Temptation—

the modern Pied Piper,

calling, willing, drawing

the soul resisting,

the brain relenting.

—Kristin Mueller

WOC 291

Page 291

List Poetry ■ A form of poetry that lists words or phrases. (Try a list poem activity.)

Rooms

There are rooms to start up in

Rooms to start out in

Rooms to start over in

Rooms to lie in

Rooms to lie about in

Rooms to lay away in . . .

—Ray Griffith

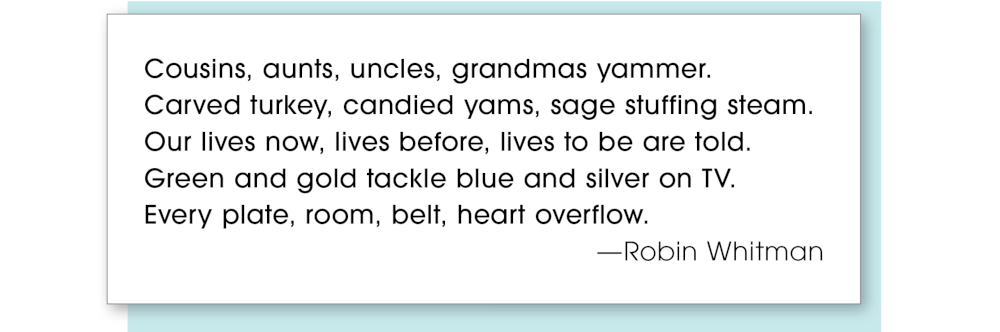

Name Poetry ■ A form of poetry in which the letters of a name are used to begin each line in the poem.

Amazing

Silly

Happy

Loud

Even though she's only two, she can still say, "I love

You!"

—Roman Leykin

Phrase Poetry ■ A form of poetry that describes an idea with a list of phrases instead of complete sentences.

foggy mist of rain

dark cement and shiny pavement

hiss of tires

silver puddles

one wet sock

—Stacie Foiles

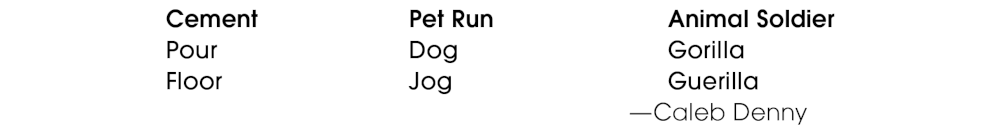

Terse Verse ■ A form of humorous verse made up of two words that rhyme, have the same number of syllables, and describe the title.

Title-Down Poetry ■ A form of poetry in which the letters that spell the subject of the poem are used to begin each line.