WOC 193

Page 193

Building Arguments

A logical argument is like a series of signs that guide your readers to a specific end point. “Start Here” and “Then Go Here” and “Next Pass This Point” and finally, “You’ve Arrived!”

The “Start Here” sign is a set of ideas that the reader should be able to accept. The next signs logically lead them to new ideas that they accept based on where they’ve been. The final sign often brings them to a totally new understanding of the situation.

This chapter will help you build convincing arguments—expressing an opinion and then logically arguing for it with strong reasons. It also helps you avoid logical detours and traps that can lead readers and yourself astray.

What’s Ahead

WOC 194

Page 194

Thinking and Writing Arguments

When making an argument (or writing persuasively), you must connect your ideas in a clear, logical way. Your writing will always be persuasive if it . . .

- argues for a meaningful point of view (opinion),

- sounds reasonable and reliable from start to finish, and

- uses convincing reasons to build its argument point by point.

Becoming a Persuasive, Logical Thinker

Follow these steps, and you’ll always be at your persuasive best.

- Choose a controversial topic (one with at least two sides).

- Gather information on your topic.

- Focus on an opinion, a claim, or a main point that you can logically support.

- Define any unfamiliar terms.

- Build an argument based on convincing evidence.

- Consider any main objections to your opinion.

- Counter (or answer) objections. Admit that there may be some truth to objections, but also point out weaknesses. (See page 205.)

- Restate or reaffirm your main opinion.

- Call the reader to act or urge the reader to accept your viewpoint.

Helpful Hint

You will probably not follow all of these steps each time you make an argument. Every situation is different and has its own special requirements.

WOC 195

Page 195

A Closer Look at Arguments

The information that follows will help you develop strong arguments.

1. Start with a worthy topic.

A persuasive writing assignment is often based on a subject your class is studying. You will, however, need to choose a topic that is controversial (something people disagree about) and specific enough for an essay. The following chart shows the difference between weak and strong topics.

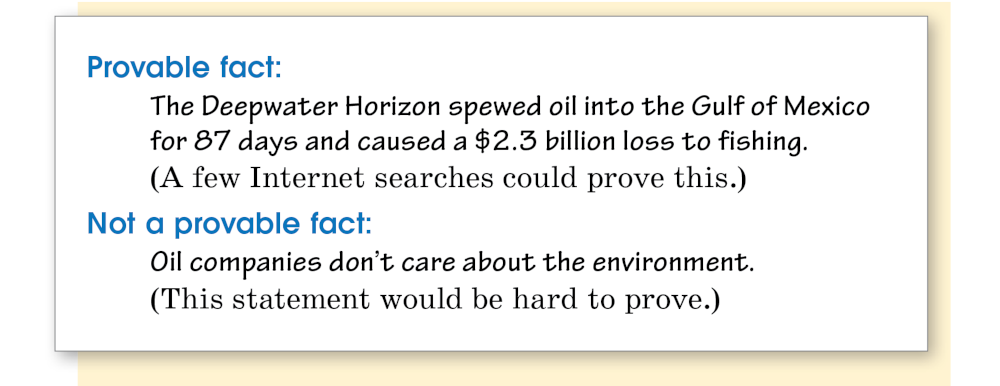

2. Know the difference between fact and opinion.

An opinion is a personal belief that can’t be directly proven. A good opinion is based on facts, but it is not a fact itself. Facts are statements that can be checked or proven to be true.

WOC 196

Page 196

3. Write an opinion statement.

Follow this simple formula to help you write a strong opinion statement.

Helpful Hint

Opinions that include absolute words—such as all, best, every, never, none, or worst—may be difficult to support. For example, an exaggerated opinion statement like “All oil drilling on land and sea should be stopped immediately” would be impossible to support.

4. Support your opinion.

Support or defend your opinion with clear, provable facts. Otherwise your reader won’t accept your argument. Note the following supporting facts.

5. Organize your facts.

You can develop an argument in two ways. You can work deductively, stating your opinion in the opening part and then supporting it in the rest of your argument. (The persuasive essay on pages 202–203 is organized in this way.) Or you can work inductively, presenting convincing evidence that leads to your opinion.

WOC 197

Page 197

Avoiding Fuzzy Thinking

Make sure that all ideas in a persuasive argument are well thought out. Poorly thought-out arguments are “fuzzy thinking”—logical detours and traps that are unconvincing. Read the descriptions that follow to learn about different types of fuzzy thinking, and avoid these in your own writing.

■ Don’t make statements that jump to conclusions.

A four-day work week would close hospitals Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays.

This statement jumps to a conclusion. Just because hospital employees might work four days per week doesn’t mean hospitals would close three days per week. Employees would simply work different days of the week, which is already the case with hospitals.

■ Don’t make statements that exaggerate how bad or good something is.

Boomers average more than eight years at a job, while Zoomers leave after just two years—a crisis for employment.

This change in average years employed is not a crisis. Boomers are old enough that some have spent more than 30 years in a top-level job, while Zoomers are young enough that most could not have more than 10 years in a starter job. Those top numbers and the type of employment change the averages.

■ Don’t make statements that are half-truths.

A four-hour work week lets workers relax for three days a week.

This statement ignores the fact that, if productivity stays the same, the worker now must accomplish five days of work in four days’ time. That’s the down-side to the three-day weekend.

■ Don’t make statements based on feelings instead of on facts.

The thought of working five days a week fills me with dread.

This statement is based on feelings. Other workers will not feel this way. A better statement would cite a study that tells what percentage of employees would prefer a four-day week to a five-day one.

Boomers average more than eight years at a job, while Zoomers leave after just two years—a crisis for employment.

This change in average years employed is not a crisis. Boomers are old enough that some have spent more than 30 years in a top-level job, while Zoomers are young enough that most could not have more than 10 years in a starter job. Those top numbers and the type of employment change the averages.

A four-hour work week lets workers relax for three days a week.

This statement ignores the fact that, if productivity stays the same, the worker now must accomplish five days of work in four days’ time. That’s the down-side to the three-day weekend.

The thought of working five days a week fills me with dread.

This statement is based on feelings. Other workers will not feel this way. A better statement would cite a study that tells what percentage of employees would prefer a four-day week to a five-day one.

WOC 198

Page 198

■ Don’t make statements just because most people agree with them.

Nobody honestly believes that people will get as much done in four days as in five.

This statement is based on the idea that if most people believe something, it must be true. But “most people” can be wrong. In fact, several studies show that people work more efficiently during a four-day work week, and companies have less employee turnover.

■ Don’t make statements that compare things that aren’t really like each other.

Offering workers a four-day week is like offering prisoners early parole for good behavior.

This statement compares workers to prisoners, as if having a job is a punishment for something they have done wrong. It also assumes that the shorter week is an incentive for workers to stop behaving badly. The comparison is misleading.

■ Don’t argue for your position by simply attacking the character of your opponents.

Of course the lazy generation who doesn’t want to work would ask for the shortest work week possible.

It is unfair to say that younger people don’t want to work and that they are lazy. Also, many of those advocating a four-day work week are from older generations.

■ Don’t create circular arguments, using the opinion as its own justification.

A four-day work week is better because four days of work is better than five days of work.

This statement argues that a course of action is best because it is best. No new reasons support the original opinion.

■ Don’t say the change leads to a “slippery slope.”

If we allow a four-day work week, soon we’ll have a four-hour week.

This argument says if you agree to a small change, the biggest possible change will occur. That’s very rarely true.

If we allow a four-day work week, soon we’ll have a four-hour week.

This argument says if you agree to a small change, the biggest possible change will occur. That’s very rarely true.