WOC 301

Page 301

Writing Research Reports

A research report requires . . . well, research. If you choose a topic that you don’t care about, that research will be grueling. If you choose a topic that really interests you, the research will be fun. So will writing the report, because that’s your chance to share the amazing things you’ve discovered.

The research report in this chapter focuses on the writer’s favorite cuisine—Chinese-American food. Did you know that fortune cookies were invented in the United States? Fun facts like these help to make a report a pleasure to read and to write. You’ll want to discover your own fun facts about a topic that you love.

What’s Ahead

WOC 302

Page 302

Writing Guidelines

Prewriting ■ Choosing a Topic

Your teacher will probably provide you with a general subject, but you will need to find a specific topic for your paper. You’ll find it much easier to write a paper about a topic that truly interests you.

Let’s say you’ve been assigned a research paper in U.S. History. Your teacher has asked you to write about a subject you have covered. Now you need to choose a specific topic for your paper.

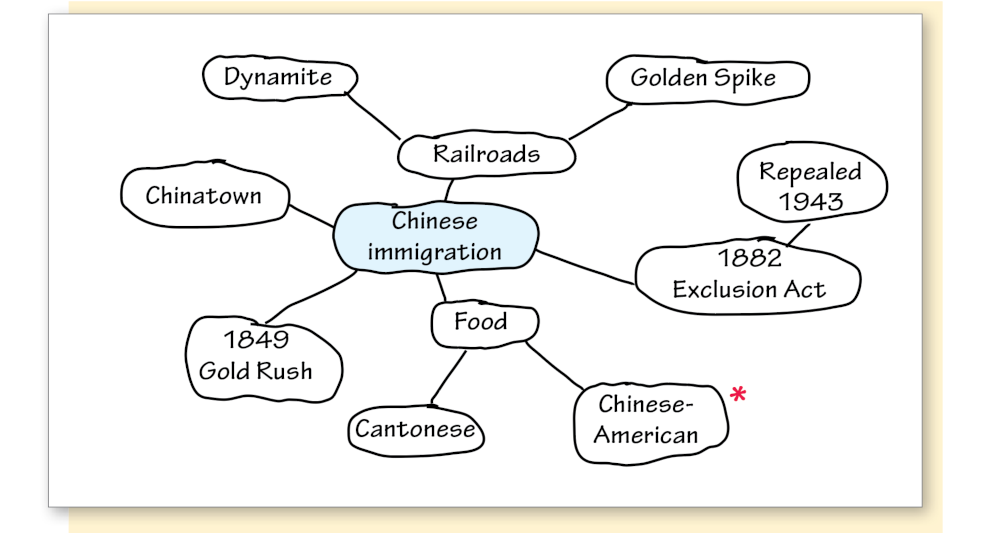

Topic Web

Completing a web or cluster is one way to search for a topic. Begin by writing the general subject in the center. Then cluster related ideas around it.

Topic Web

Helpful Hint

Clustering helps you explore a whole web of associations. Instead of thinking in a straight line, let your mind wander. Often you will discover an exciting topic by simply following your interests.

WOC 303

Page 303

Gathering Your Information

Once you have selected a topic, you need to begin gathering information about it. Find plenty of books, magazines, Web articles, and other sources on the topic. Evaluate the reliability of these sources (see pages 354–355), and then take notes on the important facts and details you find. (See pages 463–468 for additional help.)

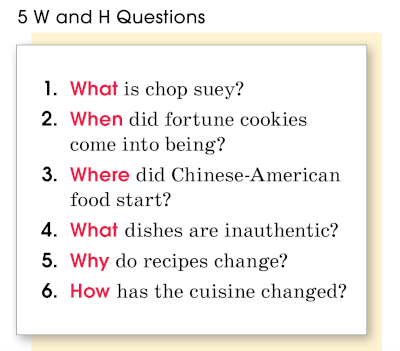

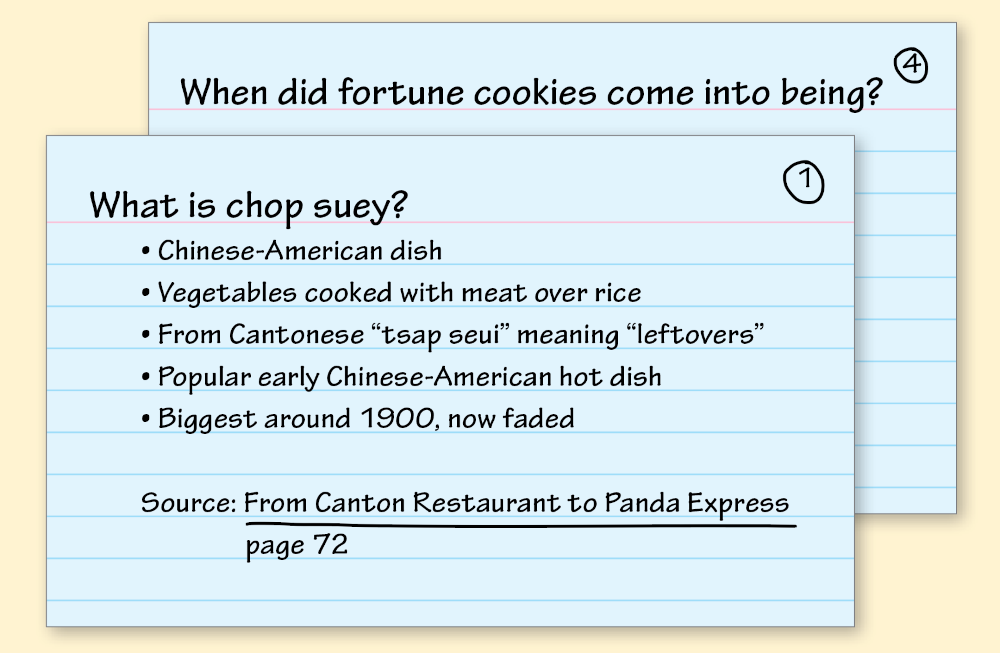

Ask questions. ■ To organize your reading and note taking, write questions that you would like to answer about your topic. Put each question at the top of a separate note card. (See the examples below.) Any time you find a fact that answers one of your questions, write it down on the appropriate card. Be sure to note the source.

Note Cards

WOC 304

Page 304

Prewriting ■ Organizing Your Information

Select a main point. ■ Once you have finished your reading and note taking, review the information you have gathered. As you do this, identify a specific part, feature, or feeling to focus on in your report. The focus of the research paper on pages 311–315 is the way Chinese-American food evolved to be its own cuisine.

Arrange your cards. ■ Keeping the focus of your paper in mind, put your note cards in the best possible order.

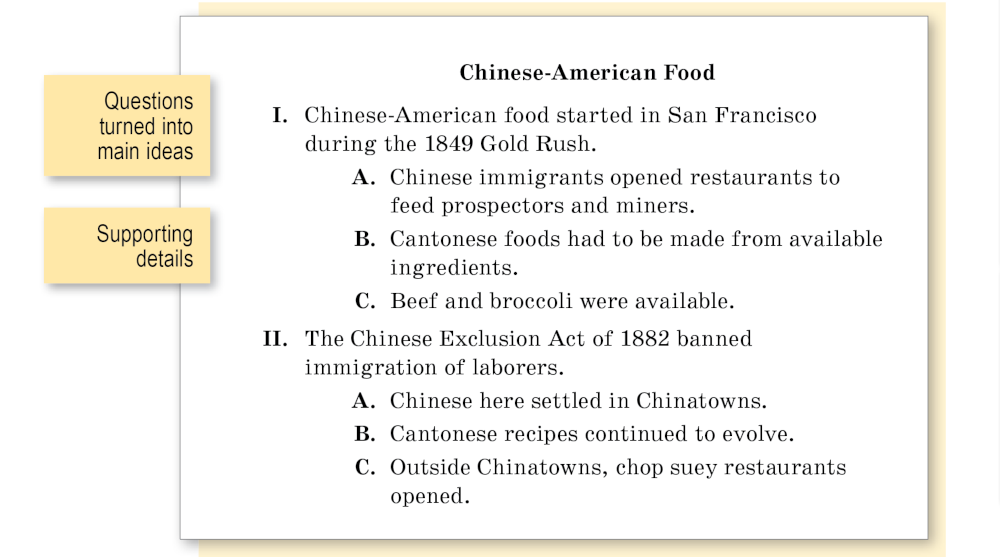

Outlining Your Information

Write a rough outline. ■ Finally, prepare an outline for the body of your paper. Begin by listing the headings (questions) written on the top of your note cards in the same order that you have just arranged them. Leave enough space between the headings to include supporting facts and details. If you are not required to include a formal outline with your report, this quick outline may be all you need.

Rewrite your outline. ■ If you are required to do a formal outline, rework your rough outline into a clear sentence outline. Reword the questions into main ideas and number them with Roman numerals: I., II., III., IV., and so on. Include supporting details under each main idea and order them with capital letters: A., B., C., and so on. (See page 109 for more information.)

WOC 305

Page 305

Considering Your Audience

At some point during your planning, you should see how well your topic matches up to the reader. Ask yourself the following questions.

Writing ■ Developing the First Draft

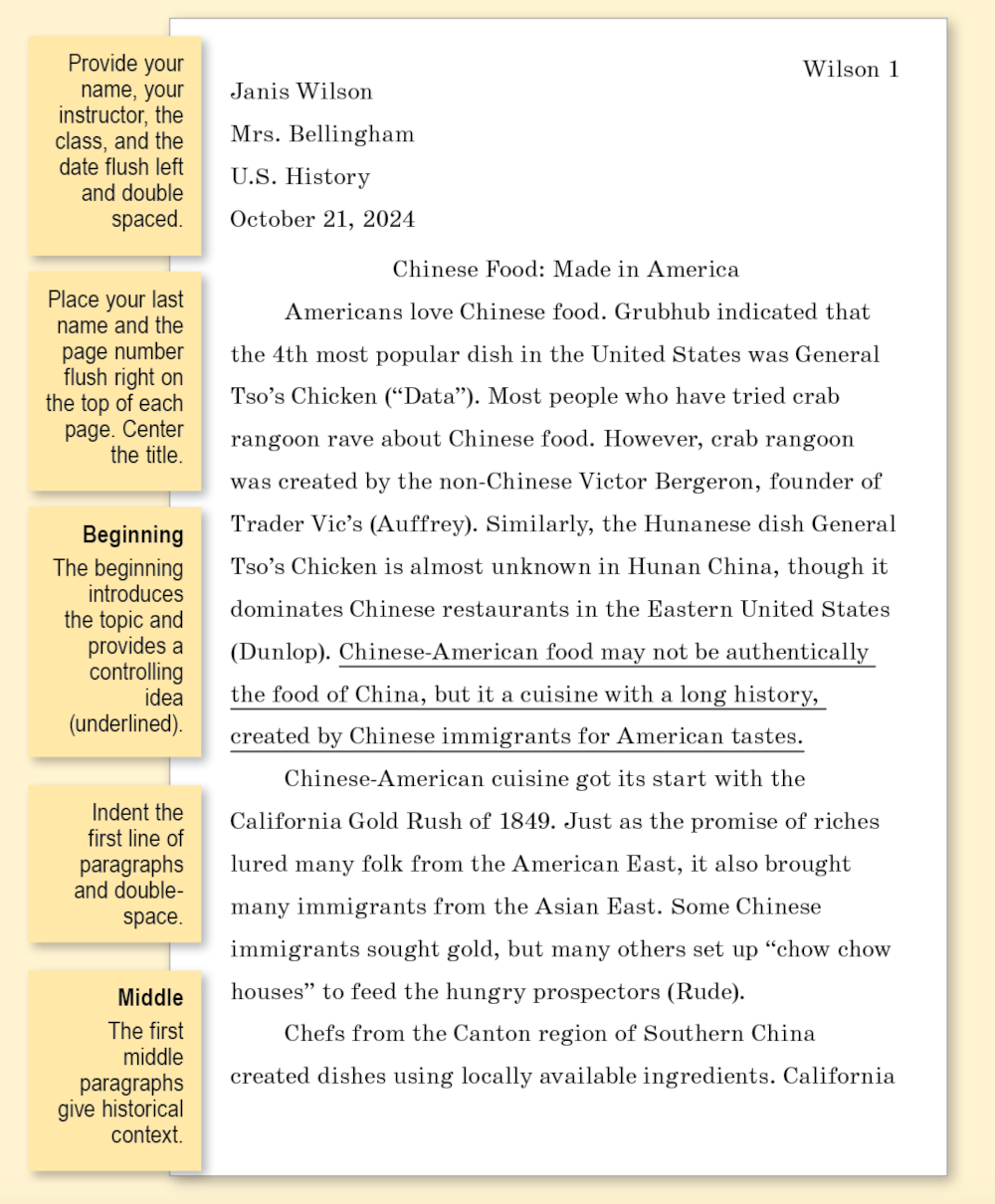

Write an opening paragraph. ■ In the first few sentences, get the reader’s attention; then write a sentence that states the topic or thesis of your paper. This sentence serves as the controlling idea for the research paper.

The writer of the research paper on page 311 identifies the topic of her report in the opening.

Controlling Idea

Chinese-American food may not be authentically the food of China, but it a cuisine with a long history, created by Chinese immigrants for American tastes.

(If you’re expected to write a thesis statement, see page 108 for help.)

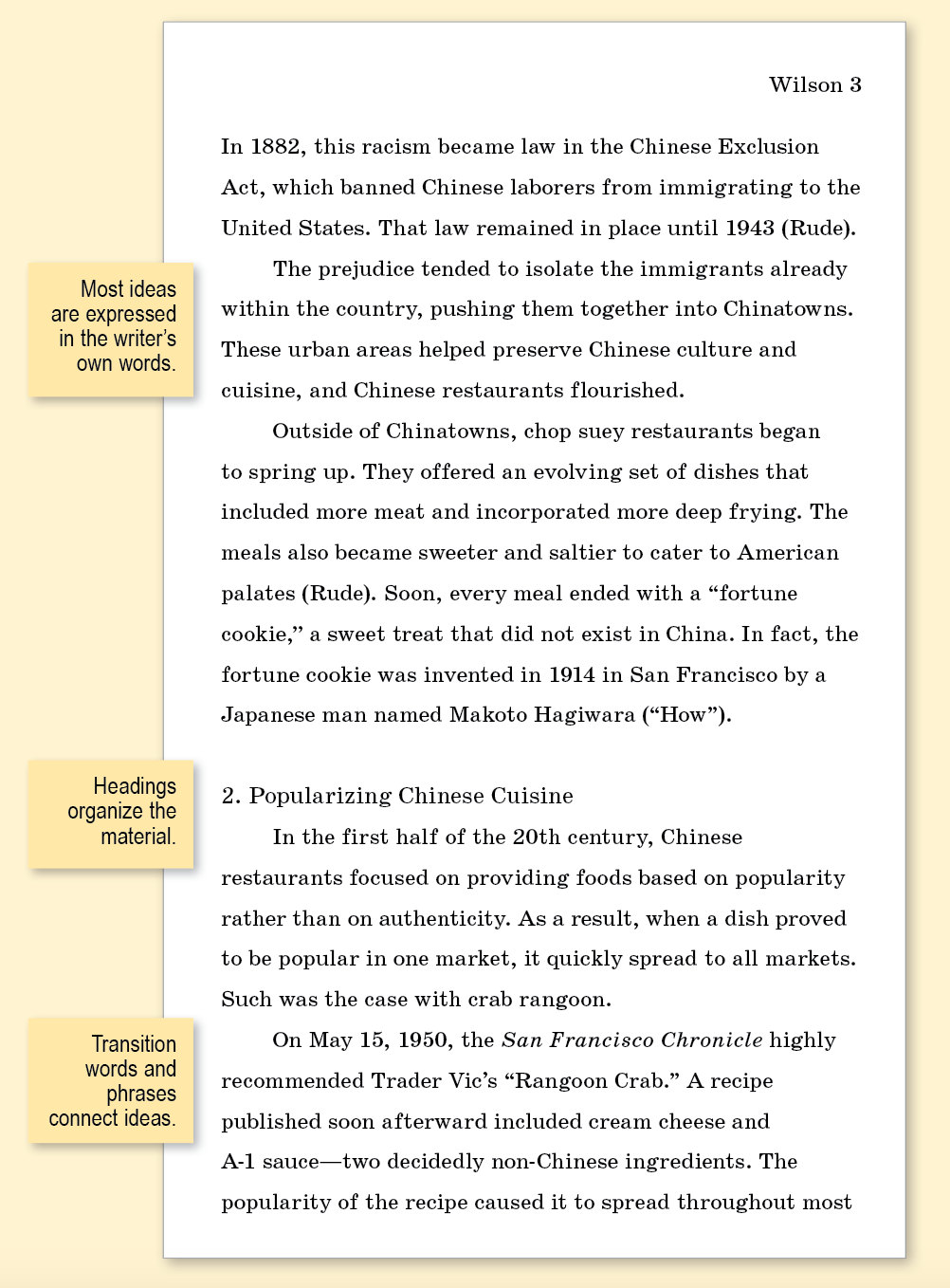

Develop the middle paragraphs. ■ Follow your outline when writing the body of your research paper. Each main point (I., II., and so on) serves as the topic sentence of a paragraph, and the details (A., B., and so on) become the supporting sentences. Also feel free to add new ideas as they come to mind.

Create an ending paragraph. ■ Use one or more of the following ideas to form an effective closing:

- Summarize your main points.

- Restate your thesis.

- Reflect on the topic.

- Make a final strong statement.

WOC 306

Page 306

Writing ■ Giving Credit for Information

Giving credit to your sources isn’t just about being honest. It’s also about supporting your ideas and helping the reader find more information about your subject. Plagiarism—which means not crediting a source—cheats you, your source, and your reader. Here are three common ways to give credit. (See also pages 297–300.)

Hyperlink ■ In an electronic document, such as a Web page or a multimedia report, you can directly link your text to the source. Some people add a sentence to do this. For example, “Click here to learn more about the creation of General Tso’s chicken.” However, it is better to fit the link naturally into your text: “General Tso’s chicken is deep fried and covered with sweet and sour sauce.”

Bibliography ■ In some instances, a bibliography may be all the documentation your teacher requires. In that case, at the end of your report, simply include an alphabetical list of sources you consulted during your research.

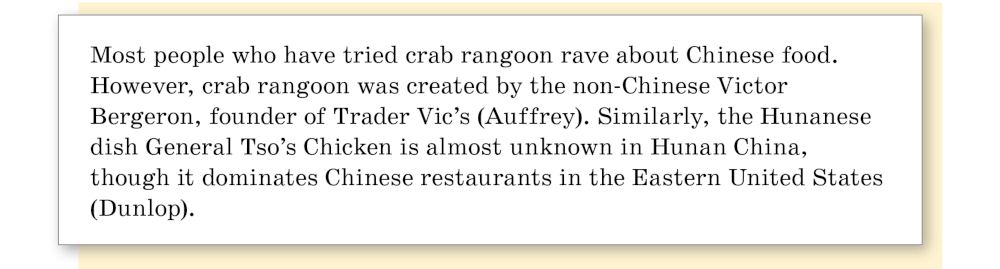

MLA Style ■ In an MLA-style report (see pages 311–315), a works-cited page lists all sources used in the paper. Within the essay, the source of each borrowed quotation, paraphrase, or fact must be identified. In the example below, facts in the first two sentences are credited to the author Auffrey, while those in the third sentence are credited to Dunlop.

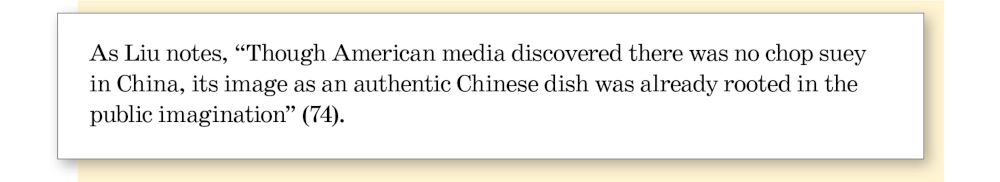

You also can work the source into the sentence itself and cite the page numbers at the end, as in this example:

WOC 307

Page 307

Revising ■ Improving Your Writing

Use the explanatory rubric or the argument rubric (page 176 or 208) as a general guide when reviewing and revising your research paper. Also keep the following points in mind.

Making Changes ■ Review your first draft to be sure it says what you want it to say. As necessary, add, rearrange, or cut ideas so that (1) your beginning paragraph gains the reader’s attention and identifies your topic or thesis, (2) each middle paragraph develops a main point about the topic, and (3) your closing paragraph keeps the reader thinking about the topic.

Getting Help ■ Have at least one other person (writing peer, teacher, family member) review your first draft. Share any concerns you have about your writing and ask if the reviewer is confused by anything or has any questions.

Documenting Your Sources ■ Be sure to give credit in your paper for ideas and direct quotations that you have borrowed from your sources. In addition, prepare a works-cited page or bibliography, listing all of the sources you have cited in your paper. (See pages 308–310 and 315 for help.)

Editing ■ Checking for Accuracy

Use the following checklist to help you edit your research paper. Also refer to the rubrics on pages 176 and 208.

Conventions Checklist

_____ Have I used proper end punctuation for my sentences?

_____ Have I capitalized first words of sentences and proper nouns?

_____ Have I used the correct forms of verbs (give, gave, given)?

_____ Do my subjects and verbs agree (Smith doesn’t, not Smith don’t)?

_____ Have I correctly punctuated direct quotations? (See pages 491–492.)

_____ Does my final copy follow the correct format assigned by my teacher?

WOC 308

Page 308

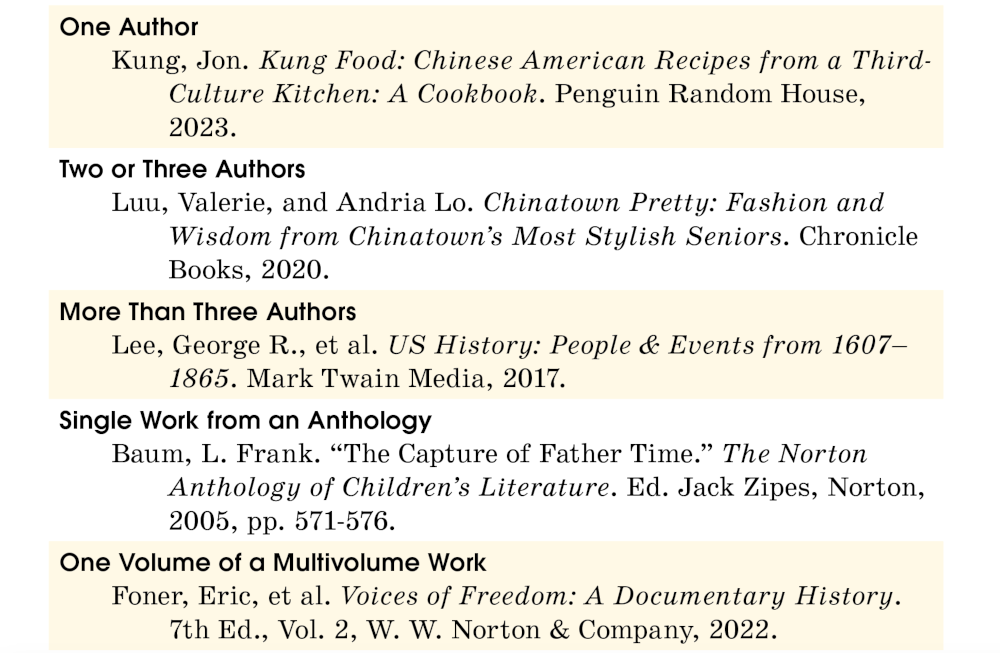

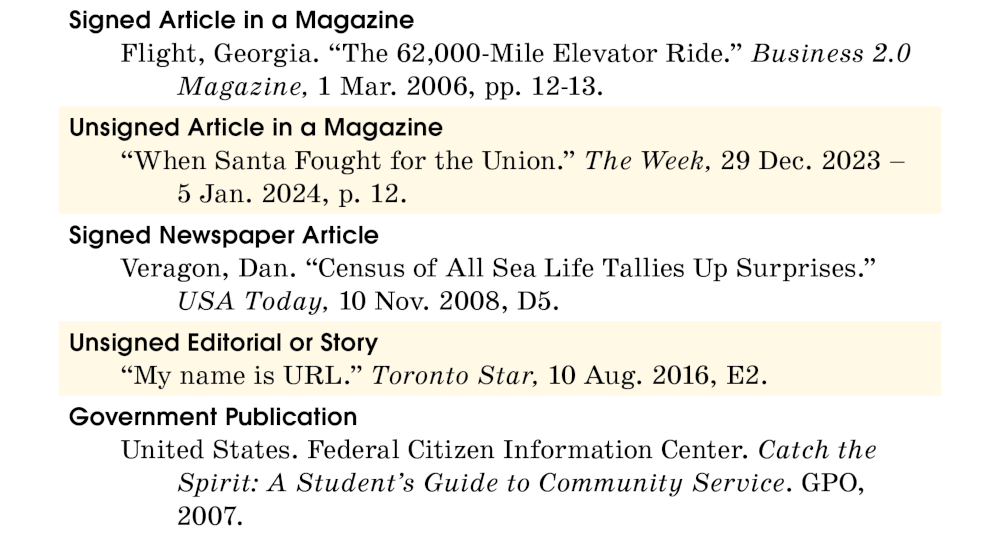

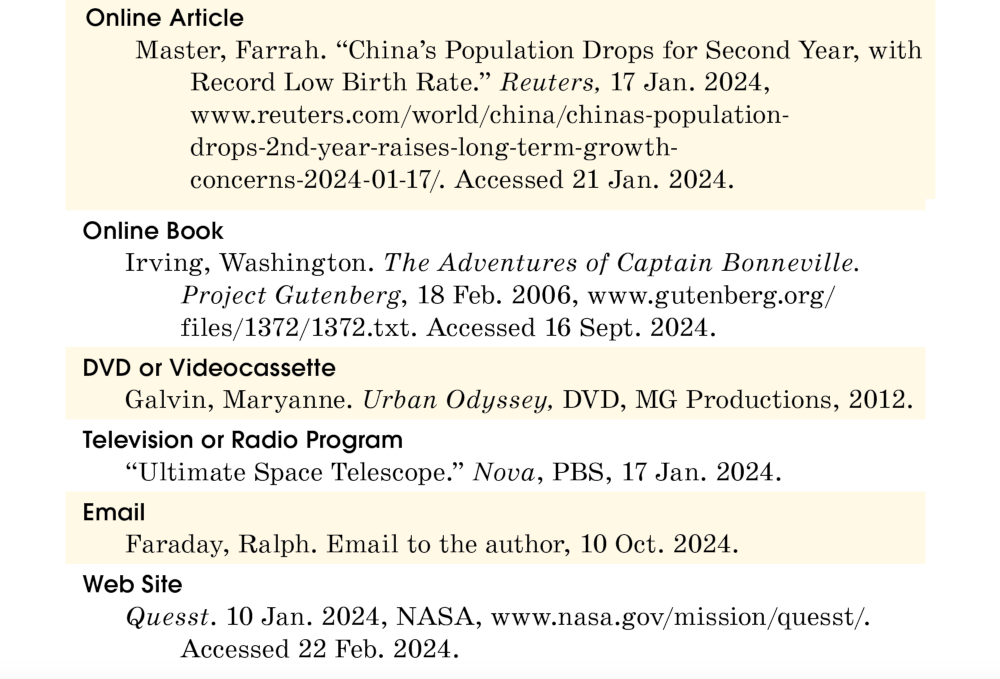

Adding an MLA Works-Cited Page

A works-cited page alphabetically lists the books and materials you refer to in your report. Double-space the information you include in your works-cited page, indenting the second line of each entry 1/2 inch. Italicize titles of longer works, such as books, plays, music albums, and magazines. (See page 493.)

You will build your works-cited entries by providing the following pieces of information in this order for each source. (Leave out information that doesn’t apply to the source.)

1. Author.

2. Title of source.

3. Title of container,

4. Other contributors,

5. Version,

6. Number,

7. Publisher,

8. Publication date,

9. Location.

Follow each piece of information with the punctuation mark shown above.

Helpful Hint

Information that can be found in a general dictionary or encyclopedia is considered common knowledge and does not require documentation. However, this doesn’t mean that you can copy the information word for word.

WOC 309

Page 309

Works-Cited Entries

Print Sources

WOC 310

Page 310

Electronic Sources

WOC 311

Page 311

MLA Research Paper

Student writer Janis Wilson wrote the following research paper about the history of her favorite cuisine.

WOC 312

Page 312

WOC 313

Page 313

WOC 314

Page 314

WOC 315

Page 315