WOC 029

Page 29

Prewriting

Imagine that you were trying to track down the Loch Ness Monster. How would you do it? You’d need to get to Scotland, hire a boat, go out on the loch with a notepad and phone—and see what happens. . . .

When you begin a writing journey, you do the same sort of activities. You gather tools and information and venture out to discover. That’s called “prewriting.”

You start prewriting by analyzing the writing assignment: What form should you write? What’s your subject, audience, and purpose? Next, you select a topic, gather information about it, and organize your ideas.

Effective prewriting pours writing possibilities into your mind. You’ll know you are done with prewriting when you want to launch into your first draft.

What’s Ahead

WOC 030

Page 30

Quick Guide ■ Prewriting

Prewriting takes you from “I don’t know what to write about” to “I’ve got so many great ideas!” Prewriting fills your mind with thoughts to share.

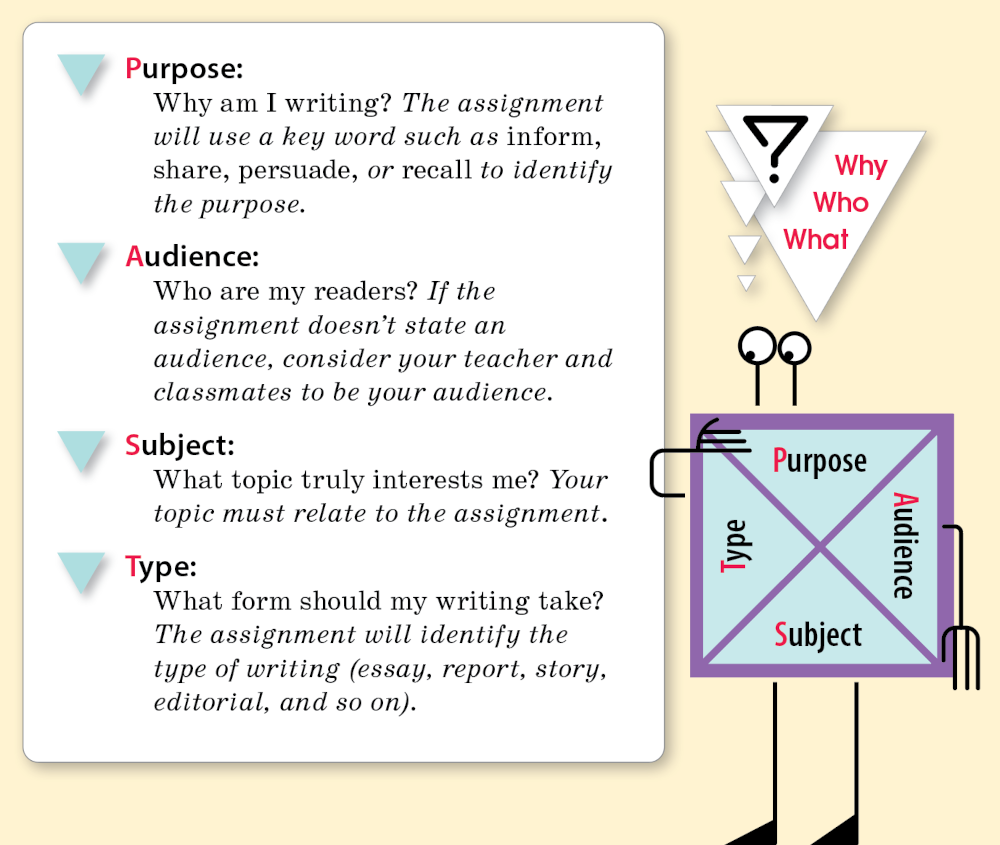

Consider the Writing Situation

Start by using the PAST strategy to identify the basic elements of your writing assignment. Doing so ensures that you will create an on-target response.

Good Thinking

Before you shoot an arrow at a target, you need to take aim. That’s what the PAST strategy helps you do: Take aim at your purpose, audience, and subject and make sure that the type of writing you create is on target.

WOC 031

Page 31

"Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them,

and pretty soon you have a dozen.”

—John Steinbeck

Creating a Writing Resource

Writers tend to be curious—observing, listening, wondering, jotting. They are like magpies, gathering shiny things and building bedazzled nests out of them. Use the strategies below to gather your own trove of shiny writing ideas.

■ Maintain a Writing Notebook or Folder

Throughout your day, interesting topics crop up. Grab them. Record them in your notebook as starting points for writing.

■ Read Like a Writer

Stay alert to ideas from your readings. Write down odd names, alternate endings, fun descriptions, interesting conflicts—anything your reading suggests. They could inspire you.

■ Watch People

Observe how they live their lives. Imagine being inside their heads, experiencing what they are experiencing.

■ Get Involved

Visit museums, churches, parks, libraries, businesses, and so on. Experiences build writing ideas.

■ Search and Research

Explore the Internet for its wealth of information. Also scout around your school or community library for ideas.

Helpful Hint

Imagine on your walk home, you see an ornate old rocking chair on the curb beside two beat-up garbage cans. A cardboard sign on the seat says, “Free to a good home.” This one encounter can inspire many writing ideas.

WOC 032

Page 32

Selecting a Topic

Use the following strategies to select specific topics that truly interest you. Learn which strategies work best for you.

Journal Writing

Write regularly in a journal or notebook, reflecting on your experiences. From time to time, review your entries and underline ideas you would like to explore further. (See pages 129–134.)

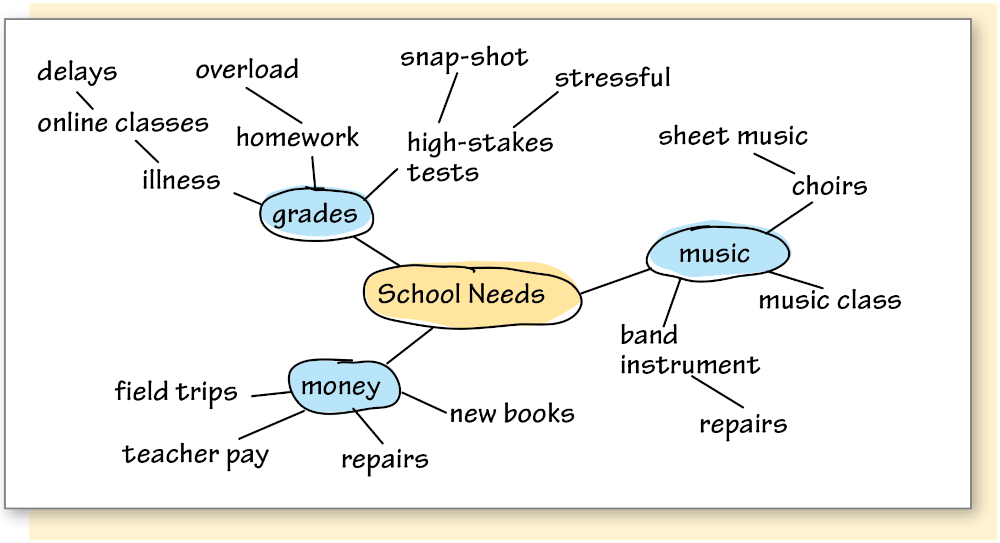

Clustering

Write down and circle a word or phrase related to your assignment. Then cluster words around the nucleus word and connect them. After clustering for a few minutes, you will begin to sense an emerging writing idea.

Helpful Hint

When you sense an emerging writing idea, stop clustering and freewrite for 5–10 minutes about the idea. (See pages 33 –34.)

Listing

Think about your writing assignment and list ideas. Keep listing for as long as you can. Then consider your ideas for a possible subject.

WOC 033

Page 33

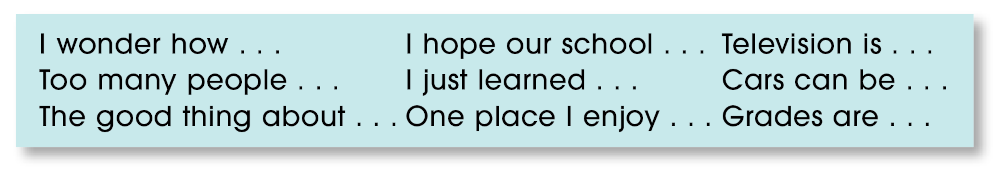

Sentence Completions

Review your writing assignment and complete open-ended sentences about it. Complete each sentence multiple times. Search your sentences for a subject to write about.

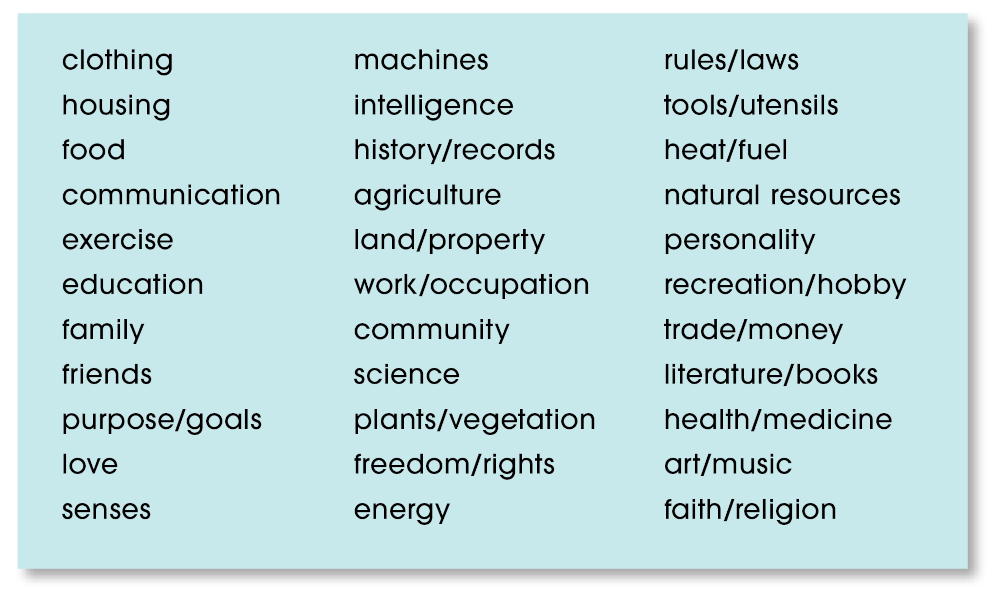

Review the Essentials of Life Checklist

Review this list of broad subjects needed for life. Then, for each subject, think of specific topics. For example, for the subject food, you could write about . . .

- how to bake bread,

- uses of seaweed in food, or

- how much water it takes to produce different kinds of food.

Freewriting

Think of your assignment and then write nonstop for 5–10 minutes to discover possible topics. Review your writing and underline any ideas that might work for the assignment. (See page 34.)

WOC 034

Page 34

Practicing Freewriting

Freewriting is an all-purpose writing tool that helps you unlock some of your best ideas and thinking. It is especially helpful for finding writing topics.

The Process

- Write nonstop for at least 5–10 minutes. Don’t stop to judge or edit your work. You are writing to explore.

- If you seek a topic for an assignment, begin writing with an idea related to the assignment.

- For personal freewriting, write about the first thing that comes to mind (or see page 134 for writing ideas).

- Stick with a certain topic for as long as you can, recording all the details that occur to you.

- Keep writing even when you are stuck. If you do get stuck, write about that until a new idea pops up.

The Result

- Review your freewriting and underline topic ideas for writing assignments.

- Mine your freewriting for particularly good sentences or paragraphs that you might use in an assignment.

- Freewrite about characters and conflicts to get story ideas. Freewrite about sensory details for poems.

- Team up with a partner to read and react to each other’s freewriting.

Helpful Hint

Freewriting helps you gain fluency—the ability to write a lot in a short period of time. It increases your confidence and improves the flow of your writing.

WOC 035

Page 35

Using Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers can help you gather and arrange details for writing. This page lists organizers for many different types of writing.

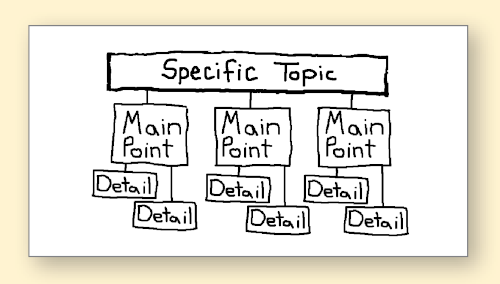

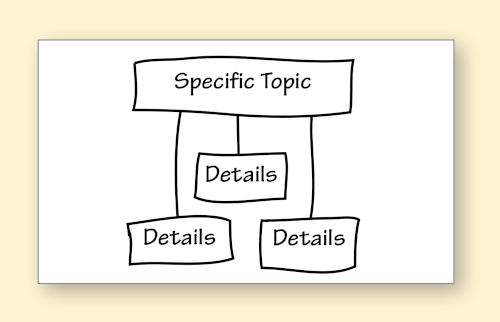

Line Diagram

To organize main points and details for explanatory essays

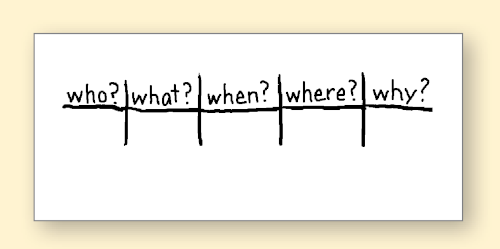

5 W’s Chart

To collect the who? what? when? where? and why? details for news stories and narratives (page 252)

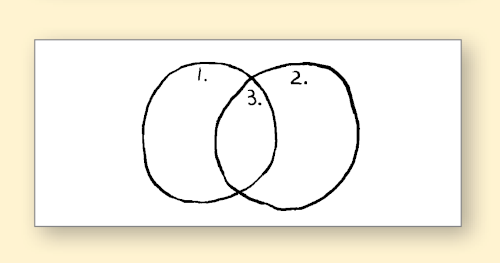

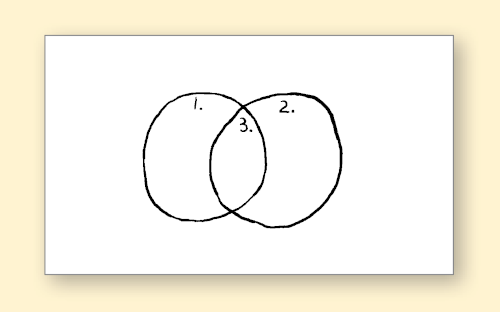

Venn Diagram

To collect details for a comparison of two subjects (page 321)

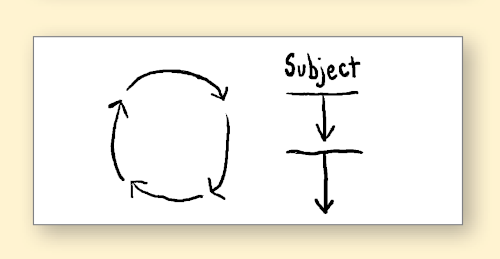

Cycle Diagram

To collect details for science-related writing, such as “how flowering plants reproduce”

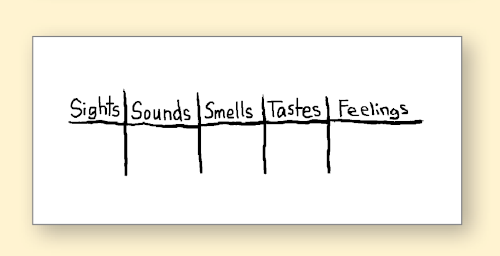

Sensory Chart

To collect details for descriptions and observation reports (page 149)

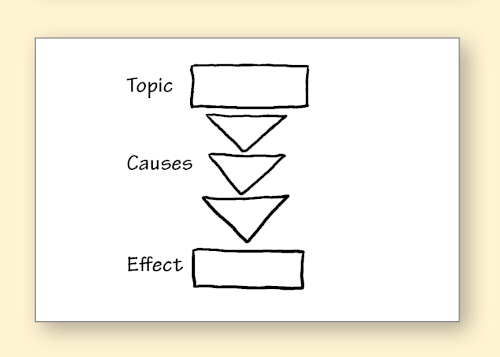

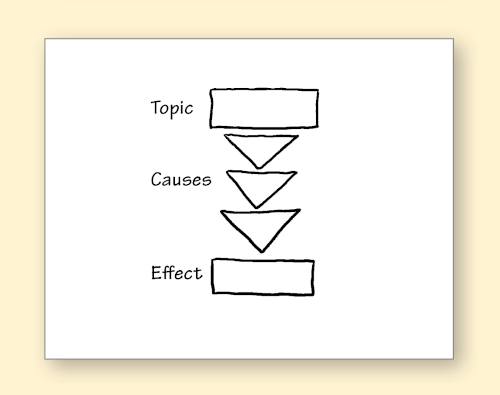

Cause-Effect Organizer

To collect details for cause-effect essays, such as “the causes and effects of metal detectors in school”

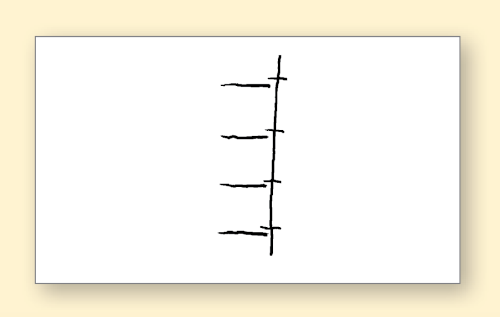

Time Line

To collect details chronologically for narratives and essays (page 156)

WOC 036

Page 36

Collecting Details

How much collecting should you do? When you know a lot about a topic, perhaps freewriting or listing will provide enough details. But when you know very little about a writing idea, you may need two or three collecting strategies. The next two pages list many of these strategies.

Gathering Your Thoughts

■ Focused Freewriting

Explore your topic from different angles by writing freely for at least 5–10 minutes. (See page 34.)

■ Flash Drafting

Complete a freely written version of your actual paper. This will tell you how much you need to learn.

■ Listing

Jot down details you already know about your topic and also questions you have about it. List for as long as you can.

■ Clustering

Create a cluster with your specific topic as the nucleus word.

■ Covering the Basics

Answer the 5 W’s—who? what? when? where? and why?—to identify basic information about your subject. Add how? for even better coverage. (See page 252.)

■ Analyzing

Think carefully about a subject by answering these types of questions:

- What parts does my topic have? (Break it down.)

- What do I see, hear, or feel when I think about it? (Describe it.)

- What is it similar to? What is it different from? (Compare it.)

- What are its strengths and weaknesses? (Evaluate it.)

- What can I do with it? How can I use it? (Apply it.)

Good Thinking

Here’s another way to think carefully about a topic: Keep asking the question Why? about your topic until you run out of answers. Then sum up what you’ve learned.

WOC 037

Page 37

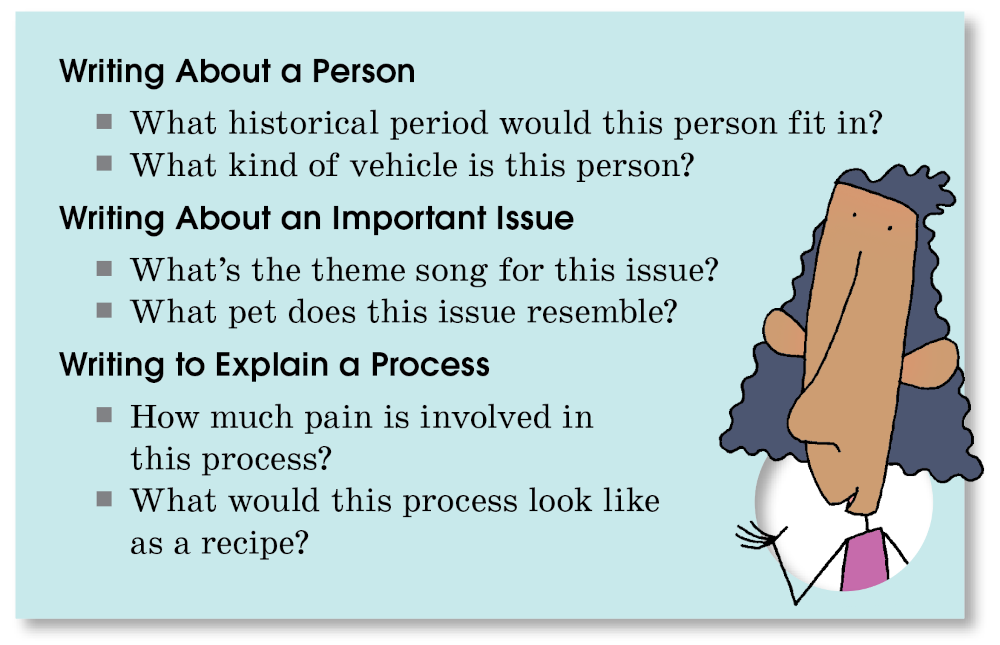

■ Imagining

Think creatively about a topic by writing and answering offbeat questions. Here are some examples:

■ Debating

Create a debate that explores your topic. You could be one of the debaters.

Researching

■ Searching

Explore the Internet for information about your topic. (See pages 358–361.)

■ Reading

Refer to nonfiction books, reference books, magazines, pamphlets, and newspapers for information about your topic.

■ Viewing

Watch television programs or movies about your topic.

■ Experiencing

Visit or watch your topic in action. If your topic involves an activity, participate in it.

Talking with Others

■ Interviewing

Interview an expert about your topic. Meet face-to-face, communicate via email, or converse on the phone.

■ Discussing

Talk with your classmates, family members, and community members to see what they have to say about the topic.

WOC 038

Page 38

Planning Your Writing

After collecting details about your topic, you need to complete two tasks before you start a first draft: (1) find a focus for your writing and (2) organize the appropriate details to support your focus.

Finding a Focus

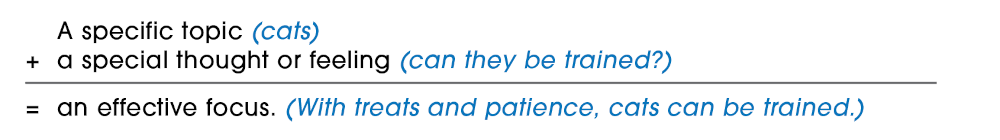

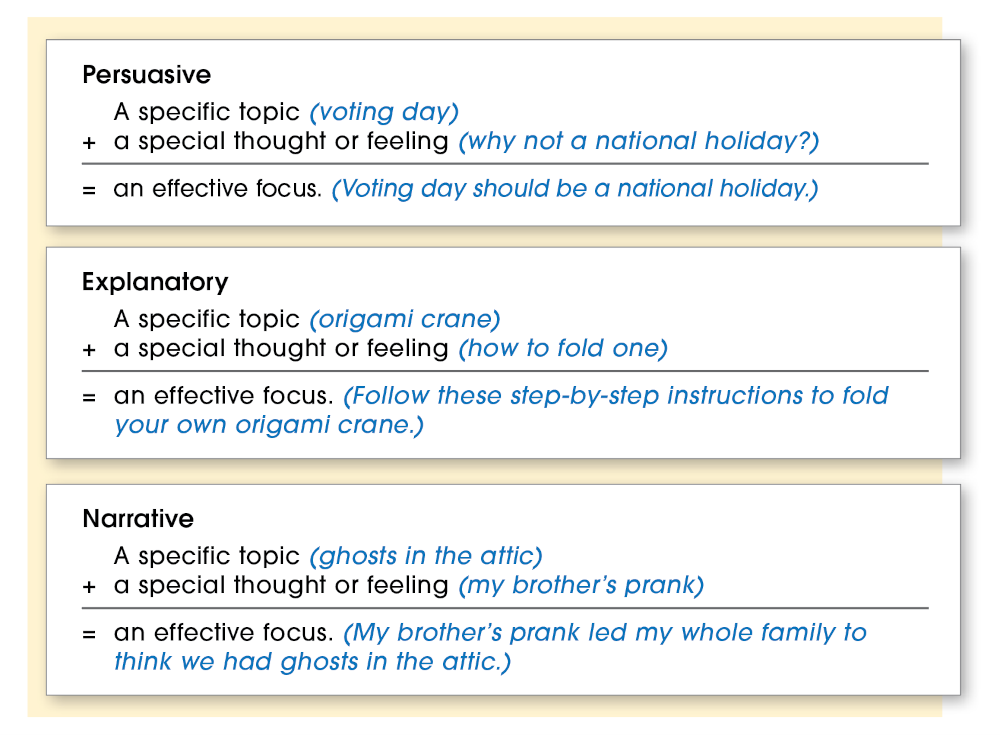

A focus is a special thought or feeling that you want to communicate about your topic. A clear focus tells the reader what you are writing about and keeps you on course. Without a focus, you won’t know what to include and what to keep out of your writing. This formula will help you establish a focus for your writing.

Sample Focus Statements

WOC 039

Page 39

The Traits of Prewriting

So far in your prewriting, you’ve gathered many ideas and found a focus for them. Now you need to organize the details that support your focus.

■ Ideas

You have selected a meaningful topic, gathered information about it, and formed a focus.

■ Organization

You need to decide on the best arrangement of the details you have collected—a master plan that holds your ideas together.

Organizing Your Details

Use a list, a cluster, an outline, or some other graphic organizer to organize details. Find the best method of organization for your writing situation:

1. Match organization to the form of writing.

For example, if you are writing a personal narrative, you would naturally organize your writing chronologically or by time.

2. Check your focus statement for a pattern.

“Butterflies and moths go through similar transformations, but they are actually quite different creatures.” This statement suggests comparison-contrast organization.

3. Review your research.

Study your supporting details to see if a particular plan of organization makes the most sense.

4. See the next page.

There you’ll find many patterns to choose from.

Helpful Hint

For some essays, you may use one main method of organization supplemented by others. For example, you might chronologically narrate a Civil War battle but spend one paragraph contrasting the two generals.

WOC 040

Page 40

Methods of Organization

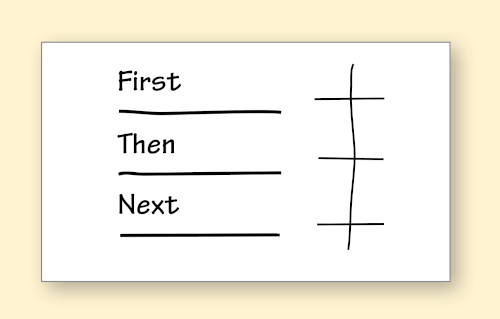

Chronological Order

Arrange details in the order in which they happen (first, then, next). Time order works well for narratives and process essays.

Order of Location

Describe details from left to right, top to bottom, edge to center, and so on. Order of location works well for descriptions.

Logical Order

Lead logically from one main point to the next. Logical order works well for essays that explain or share information.

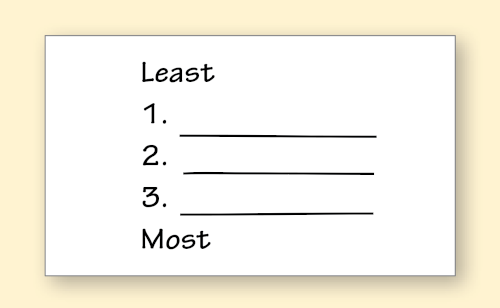

Order of Importance

Arrange details from the most

important to the least—or the other

way around. Order of importance works well for arguments or persuasion.

Cause-Effect

Make connections between the causes of a certain event and the effects. This method works well for cause-effect essays.

Comparison-Contrast

Compare two topics (show similarities), and then contrast them (show differences).