You routinely connect writing with reading, but how often do you connect writing with media literacy? It's a symbiotic relationship. You teach students to write about different topics for different audiences and purposes. They can use the same skills to engage media about different topics for different audiences and purposes.

Most writing teachers, though, wouldn’t consider themselves media-literacy coaches. They might not even know how to define media literacy: the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create communication in various media formats.

The same critical-thinking skills you teach in the writing process can help your students evaluate media for truth, fairness, and bias—skills increasingly necessary for academic success and responsible citizenship. Likewise, developing media-literacy skills prepares students to ethically share ideas in writing.

How can the writing process teach media literacy?

Students learn that good writing takes time—prewriting, writing, revising, and editing. As the old saying goes, "Easy writing makes hard reading, and hard writing makes easy reading." So students learn to appreciate well-crafted ideas—and, equally importantly, dismiss shoddy ideas when media are slapped together. Thoughtful writers make thoughtful readers, listeners, and viewers.

Let's look at each stage of the writing process to see how it can help you teach media literacy.

Prewriting

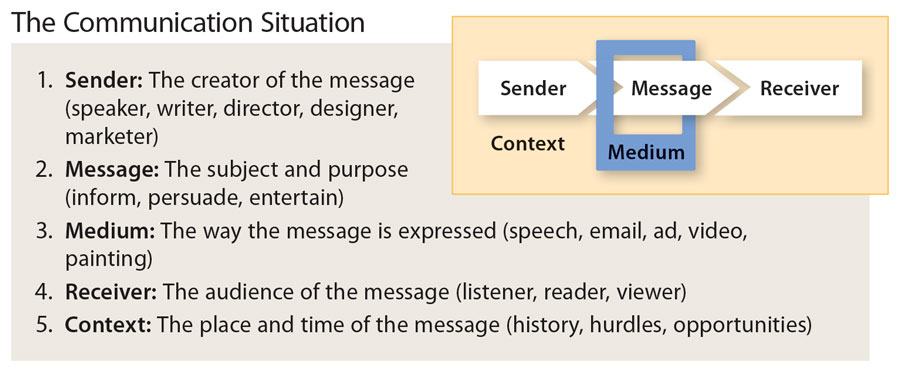

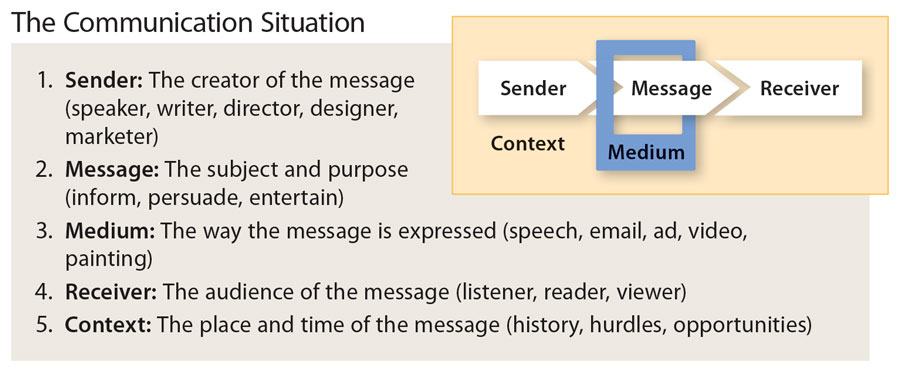

To meet the specific demands of a writing task, students should first consider the communication situation—sender, message, medium, receiver, and context:

Students who can analyze the rhetorical situation for writing can also analyze the same situation for the media they consume. All media is constructed, so all students can learn to deconstruct it—breaking it into its parts, considering how they work, and evaluating them. This rhetorical awareness helps students use sources ethically and reject media that uses them unethically.

This video can introduce the communication situation to your students: