Student Model

Setting in Crane and O’Connor

The settings in the works of Stephen Crane and Flannery O’Connor serve as more than passive backdrops. Both authors use setting to influence characters’ actions, highlight social codes, establish mood, and reveal theme. Unlike some of their contemporaries, these authors do not romanticize place and time but instead portray the harshness, apathy, immorality, and materialism of their distinct settings. Through this lens, readers experience characters attempting to navigate worlds that isolate them and determine their futures.

Crane’s novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets is set in Rum Alley, a crowded 19th-century tenement neighborhood in New York City. It begins with a scene of tattered youth brawling on a heap of gravel. During the fight, Crane provides a spatial tour of the area, beginning with the rubble on the ground, moving to an apartment house rising “from amid squat ignorant stables,” then noting a “passive tugboat” along the river, and finally describing a “gray ominous building” isolated on a river island. After the fight, Jimmy and Maggie follow their father through the bowels of Rum Alley, where they pass dark careening buildings, “gruesome” doorways, and yellow-dusted cobblestone streets. Such exposition produces a foreboding mood that will pervade the story. In particular, Crane’s use of adjectives (“passive,” “ignorant,” “gray,” “ominous”) points to a suffocating environment of indifferent, doomful squalor.

However, it isn’t merely physical space that restricts Maggie’s chances. The story’s social setting also works against her. As a poor female in the tenements, her class and gender offer limited opportunities for economic and social mobility. Her brother Jimmy spells out her options: work at a factory or turn to prostitution. Maggie initially chooses the factory only to find that the sweatshop fails to provide opportunity for advancement. Crane uses the sweatshop as an ironic vehicle, forcing Maggie to labor over the ornate upper-class clothing she longs to wear. In Rum Alley, clothing indicates status, so Maggie is drawn to the garish dresses worn by melodrama actresses. This interest sparks her romantic attraction to Pete, which eventually leads to her spiral into prostitution. In the end, Maggie’s physical and social environments imprison and isolate her to the point of ruin.

Unlike Crane's crowded urban environment, Flannery O’Connor sets “Good Country People” on a mid-20th century tenant farm in the pastoral countryside of the Deep South (presumably Georgia). In this and other works, O’Connor uses setting to expose dominant regional values and faithlessness hiding in plain sight. Just as Rum Alley isolates Maggie, the “Good Country” farmstead traps Mrs. Hopewell and Joy and reinforces their polarized worldviews. Mrs. Hopewell identifies as a sophisticated Southern “lady,” someone who values material objects, social status, and a paternalistic society but lacks self-awareness, empathy, and authentic faith. Joy identifies as an educated nihilist who rejects the Southern “lady” archetype, but her brooding nature and superiority complex are self-limiting. With limited exposure to the outside world, the characters’ interactions perpetuate each other’s worldviews and deepen their shortsighted estimation of “good country people.” It is not until an outside force (the Bible salesmen) disrupts the setting that Joy’s self-identity is challenged and changed. Interestingly, Joy’s moment of grace comes after a change in setting—away from the familiar farmhouse and into further isolation of the barn.

Unlike Crane’s novella, which radiates despair and indifference, “Good Country People” has a darkly humorous mood and a critical tone. The story’s social setting provides O’Connor with ample ammo for her critique of the South’s material and spiritual shortcomings. Mrs. Hopewell embodies a lack of substance in a cliché-ridden culture. Joy displays the limits of education and the folly of nihilism. Mrs. Freeman exposes the false stereotypes of classism, and Manley Pointer represents the hollowness of attention-seeking displays of Christianity.

Both authors’ fictional settings reflect unromantic mannerisms of distinct times and places. Their settings isolate and limit their characters while revealing socially constructed contradictions. But while Crane’s use of setting serves his thematic view of the universe’s complete indifference to humankind, O’Connor sets characters in times and places that expose moral corruption and offer grace in the face of the grotesque.

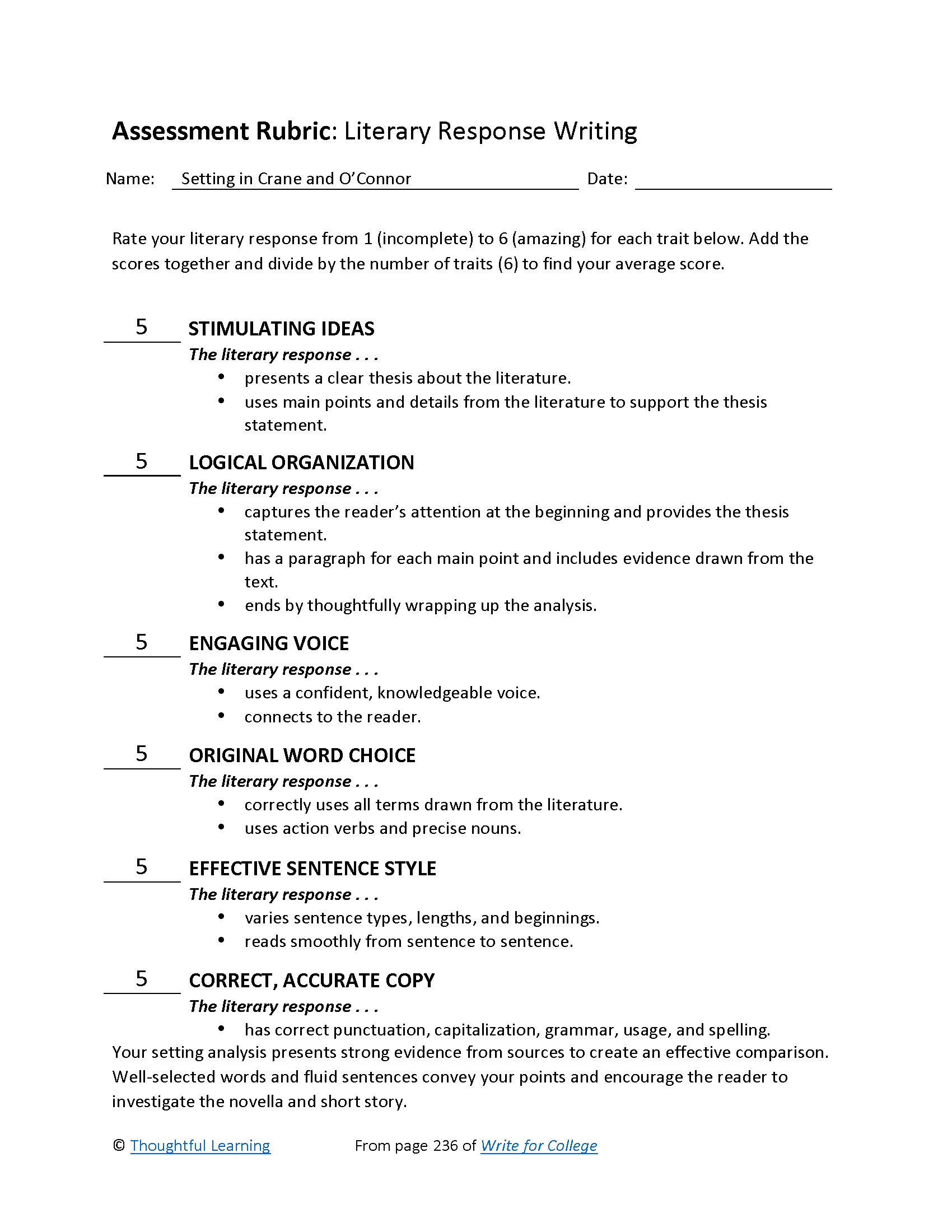

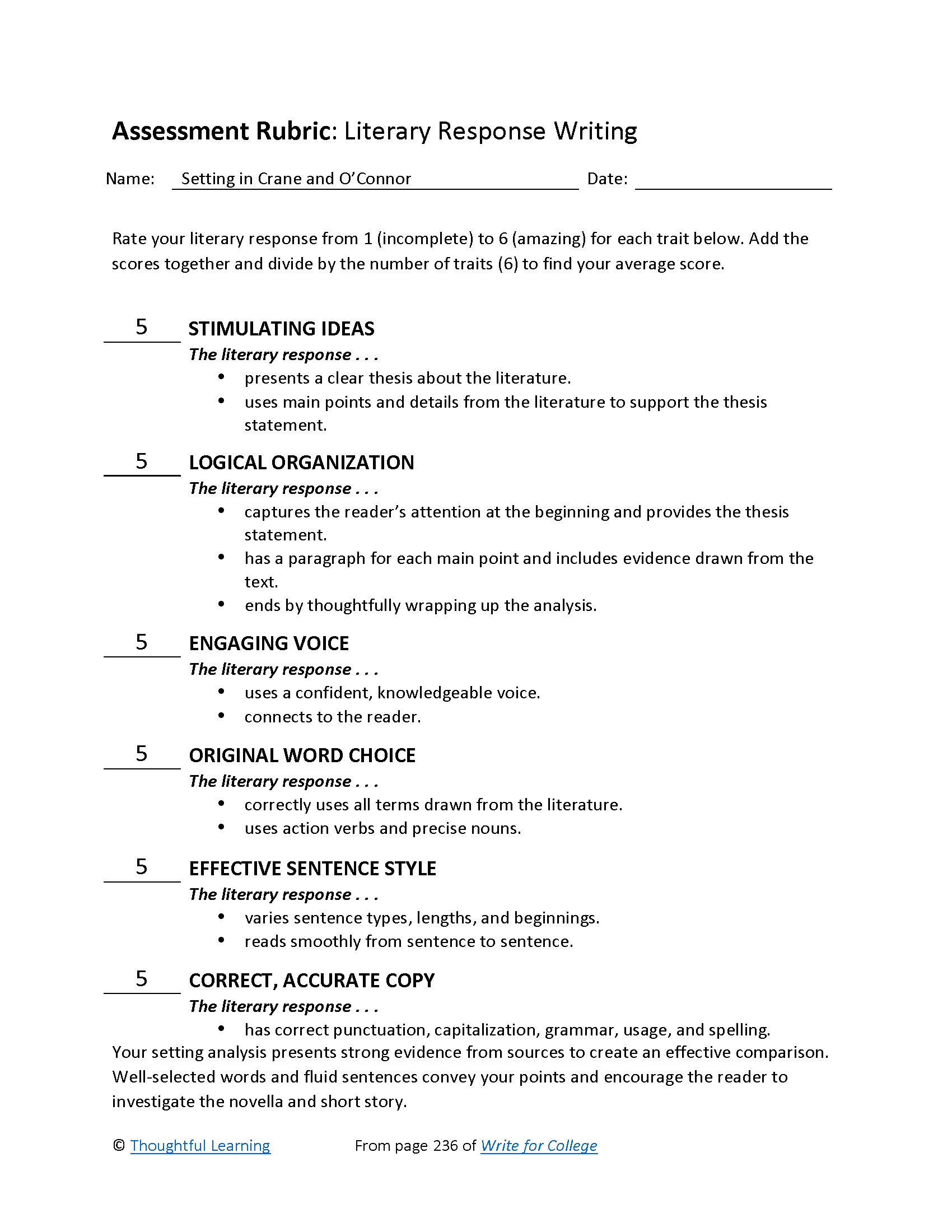

Rubric

Setting in Crane and O'Connor by Thoughtful Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at k12.thoughtfullearning.com/assessmentmodels/setting-crane-and-oconnor.