Student Model

Hmong: From Allies to Neighbors

Hmong Americans are among the most misunderstood ethnic groups. They came from China, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, but now live in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Obviously, they sometimes struggle to get along with their new neighbors. Still, Hmong helped the United States during the Vietnam War, so they've earned the right to be here. Hmong also struggle within their own communities, trying to decide how much they will hold to the old ways and how much they will become new Americans.

The Hmong have always wanted to live free, but they always were in other peoples' nations. Back in the 1700s, they were highland farmers in China but had to flee to Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. During the Laotian Civil War in the mid 1900s, Hmong fought for the government against the communists (Bankston). The U.S. saw them as allies and trained the Hmong to fight the communists. They even helped the CIA Secret War (Her and Buley-Meissner 79). In the end, the communists won, and the Hmong were now hunted. A hundred thousand fled Laos to Thai refugee camps, but thirty thousand were killed (Duffy 11).

So the Hmong immigrated to their old ally, the U.S., starting in the 1970s. They arrived in major cities, which were foreign to farmers, and Hmong faced racism. Nobody knew they had helped the U.S. during Vietnam (“Bridging the Shores”). A major migration occurred in the 1980s because the Refugee Act of 1980 let family members of the Hmong Secret Army from the Vietnam War immigrate to the United States. Most of those immigrants settled in farming town in northern California, a much better fit for them (Lai and Arguelles). In the 1990s, the Thai government threatened to forcibly send the rest of their Hmong refugees back to Laos. During that time, many Hmong settled in Minnesota and Wisconsin, but the U.S. waited until 2004 to let in 15,000 Hmong immigrants from the last big refugee camp in Thailand. Now, 260,073 Hmong live in America with 91,000 in California, 66,181 in Minnesota, and 49,240 in Wisconsin (“2010 Census”).

Hmong chose these states for their fertile soil and farming culture, which best matched their homeland experience. Hmong also appreciated the farmland values of family, interdependence, and local control. They are very loyal to their extensive families, with grandparents, children, grandchildren, and cousins living together (Lai and Arguelles). Despite their similarity to the farming communities they joined, Hmong customs often clashed with American customs. Their 14-16 year old girls were not allowed to marry, though that was their custom. Their large families put a strain on housing. Also, because the younger Hmong knew English better, they had to deal with the outside world, taking away the power of the older generation, which they didn't like.

Of course, it's hard to find a good-paying job even if you speak English, and even those Hmong who could speak it struggled to read and write it. Also, they had farm skills, not factory skills. Owning their own farms was too expensive, so they had to work as menial labor on other people's farms. Men tried to support big families on poor wages (they didn't want their women to work outside the home at first). As a result, in the 1990s, about two-thirds of Hmong Americans were considered poor (Bankston). About half were on federal welfare programs (Her and Buley-Meissner 121). Conditions are improving, but the poverty rate among the Hmong is still high (Lai and Arguelles). Now many Hmong, including women, work outside the home, and others have started small businesses and coop farms (Bankston).

Today, 61 percent of Hmong Americans have graduated from high school, which closely matches the 60 percent of Hmong who were born in the U.S. (Vang 3). This younger generation is Americanized, less bound by traditional Hmong customs than first-generation immigrants (“Bridging the Shores”). Young Hmong Americans are campaigning for women’s rights and speaking out against domestic abuse, as well as rejecting some traditional customs such as teenage brides (Lai and Arguelles). Even so, Hmong culture remains traditional, celebrating holidays from the old country and maintaining the practice of marriage dowries (“Bridging the Shores”).

Hmong Americans are doing better now than ever before, but they still fight for academic and workplace achievements. They also fight to hold onto their heritage and to remember the long road of sacrifice that brought them to this brighter day. They fought for this country even before they moved to this country. Now they fight to make their way in the country they helped defend.

Works Cited

Bankston III, Carl L. “Hmong Americans.” Countries and Their Cultures, www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/Hmong-Americans.html.

“Bridging the Shores: The Hmong-American Experience.” Wisconsin Public Radio. WERN, Madison, 12 Sept. 2008.

Duffy, John, et. al. "The Hmong: An Introduction to Their History and Culture." Culture Profile No. 18, June 2004, pp. 11-12, www.culturalorientation.net/content/download/1373/7978/version/1/file/The+Hmong%2C+Culture+Profile.pdf.

George, William Lloyd, and Chiang Mai. “Hmong Refugees Live in Fear in Laos and Thailand.” Time, 24 July 2010, content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2005706,00.html.

Her, Vincent K., and Mary Louise Buley-Meissner. Hmong and American: From Refugees to Citizens. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Lai, Eric, and Dennis Arguelles. The New Face of Asian Pacific America: Numbers, Diversity, and Change in the 21st Century. UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 1998.

“2010 Census Hmong Populations by State.” Hmong American Partnership 2010, www.vuenational.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/2010-Hmong-Census.pdf.

Vang, Christopher T. “Hmong-American K-12 Students and the Academic Skills Needed for a College Education: A Review of the Existing Literature and Suggestions for Future Research.” Hmong Studies Journal, no. 5, 2004, pp. 1-31.

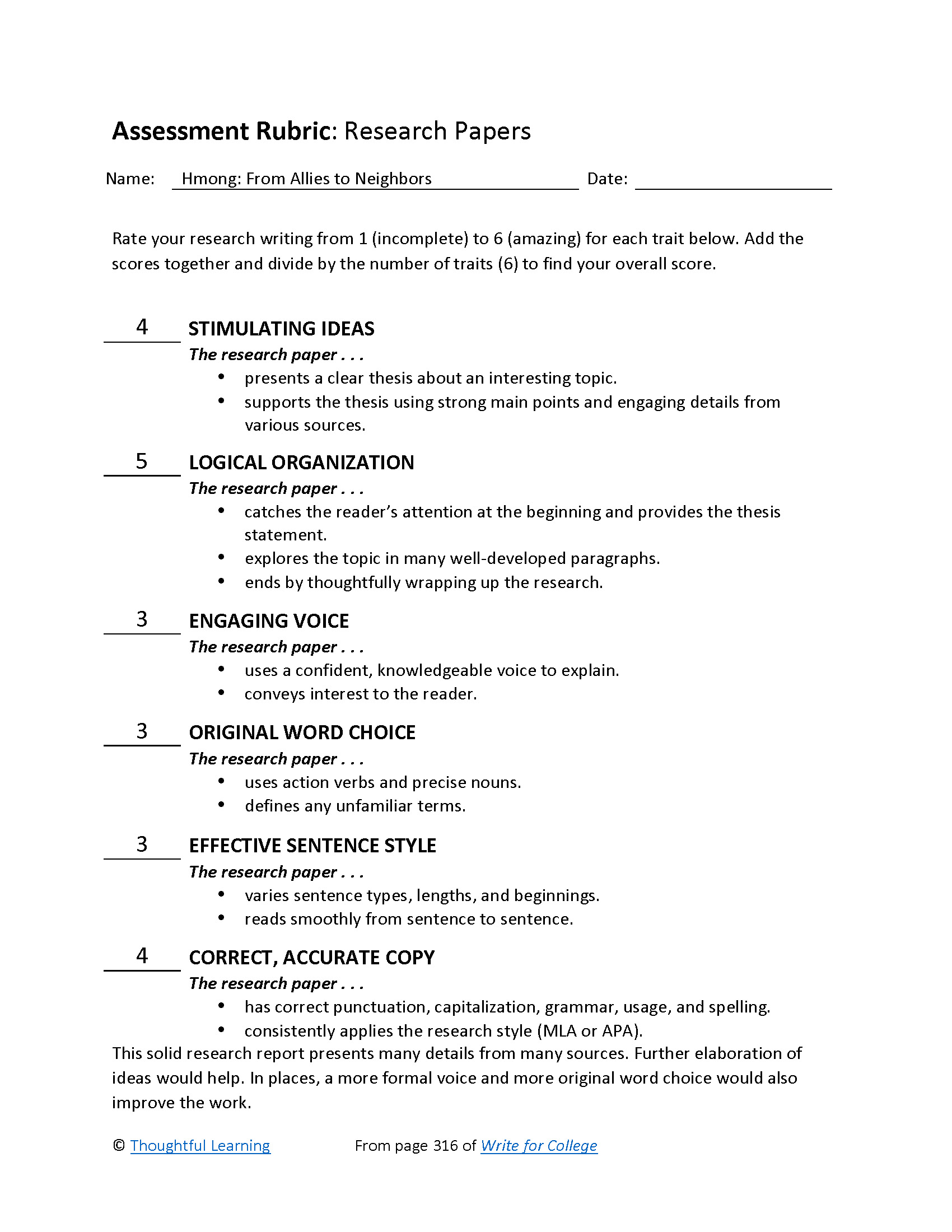

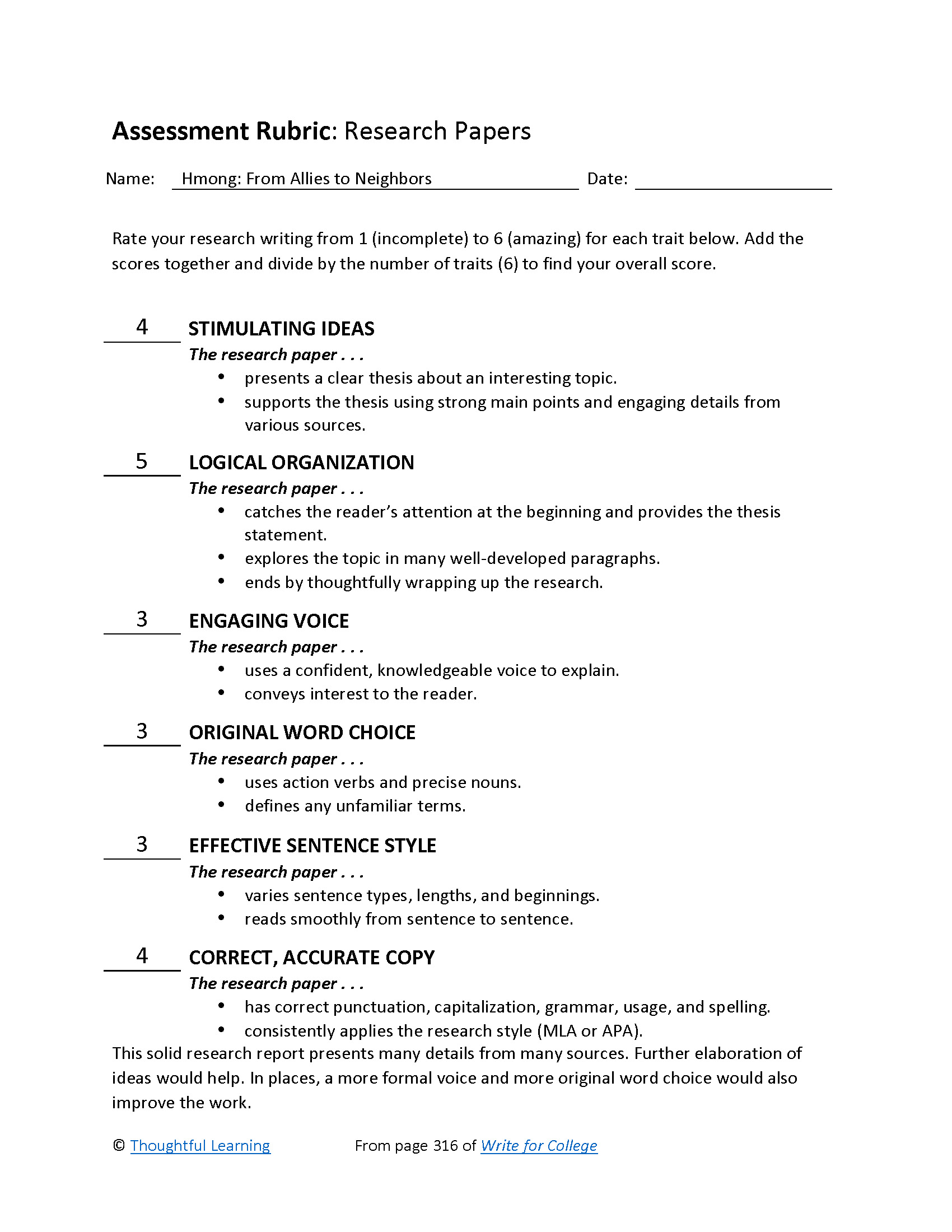

Rubric

Hmong: From Allies to Neighbors by Thoughtful Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at k12.thoughtfullearning.com/assessmentmodels/hmong-allies-neighbors.