“How come so many houses here are made with red brick? What animals live in Forest Park? How does the old water tower work? What was that abandoned warehouse near the river used for?”

Students in my freshmen composition course are curious about their community. Their surroundings offer a rich tapestry for inquiry, and I want them to dig in and pursue answers. I invite them to do so through a community-based inquiry project that stands in place of a traditional research paper.

You can facilitate a similar project to connect students to their community and drive personalized learning. Have students follow the inquiry process to create a multimedia project that explores a local curiosity.

What is the inquiry process?

The inquiry process is all about asking questions and following a series of steps to find answers or discover new questions worth pursuing. Students can follow these steps to manage everything from major school projects to minor household chores.

How can I facilitate community-based inquiry?

The following section shows the steps of inquiry in action in my classroom. Get takeaways and downloads for your own classroom.

1. Questioning

To introduce the concept of community inquiry, I play a podcast from the show “Curious Louis” from St. Louis Public Radio. In the episode, a listener wants to know, “What happens to all those used baseballs at Busch Stadium?” The Curious Louis team turns this inventive question into the topic of a short podcast and a digital news story. As a class, we talk about ways the reporter researched and presented the story, as both a podcast and a multimedia news story. The example demonstrates community-based inquiry and digital storytelling.

Students brainstorm their own “Curious Louis” questions. I ask them to pay close attention to their surroundings as they travel to and from school. What do they notice? What makes them wonder? What questions do you have about it?

TakeawaysYour students don’t need to live in a big city or attend a professional baseball game to find a question to explore. Questioning something familiar, or observing an ordinary topic in a new way, can uncover a great topic of community-based inquiry. To brainstorm ideas, have students fill out a “Community Questions Organizer.” Then have them pick their favorite question as the preliminary topic for their inquiry project. |

2. Planning

After my students pick a topic of inquiry, they decide what type of project to pursue. I normally have students build a Google Site about their topic, but they can propose other projects that better fit their purpose. For example, a student researching about an overcrowded animal shelter might create a public service announcement (PSA) about the problem. (This list gives other project ideas.)

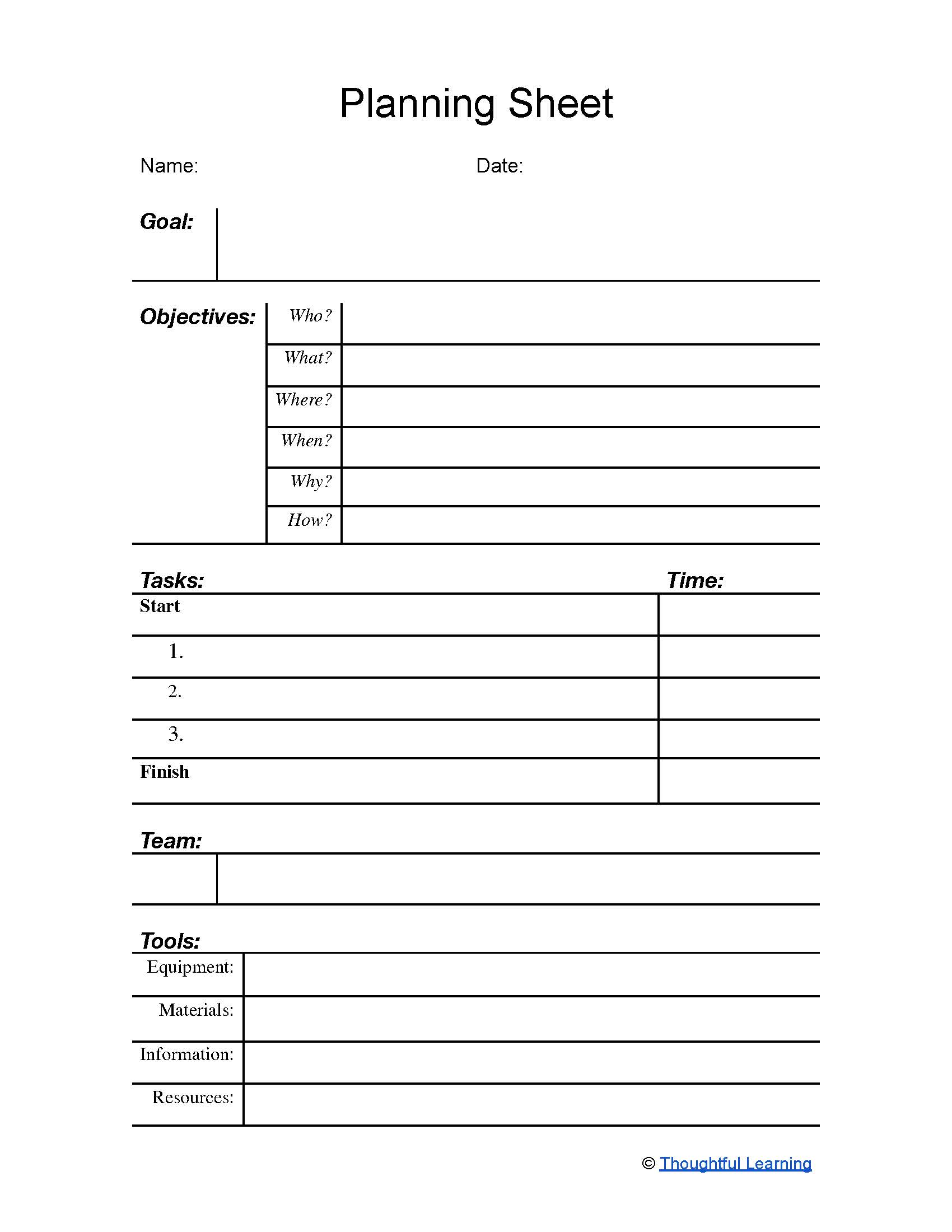

With a project in mind, students fill out a planning sheet, which includes goals, objectives, tasks, time, team, and tools. The planning sheet also serves as a project proposal, letting me give early feedback or request changes.

Download a project planning sheet.

TakeawaysAssign a project that fits your desired learning outcomes. In my experience, students enjoy creating multimedia projects that combine text and audio-visual elements. |

3. Researching

To start the research process, I ask students to gather images related to their topics. Ideally, students can visit the site of inquiry and take pictures, but that is not always possible. In those cases, students can use Google Images or other digital alternatives. Students study the images and ask new questions based on their observations. Those questions lead to further research.

Students search for answers using a mix of primary and secondary sources. While students research, I share models and examples of past projects. We discuss different ways to gather information, including online searches, library visits, interviews, personal observations, and more.

TakeawaysIncorporate media-literacy minilessons to help students find, evaluate, and organize sources. When online resources about a local topic are limited, point students to relevant community resources, such as a library or historical society. Also encourage primary research. |

4. Creating

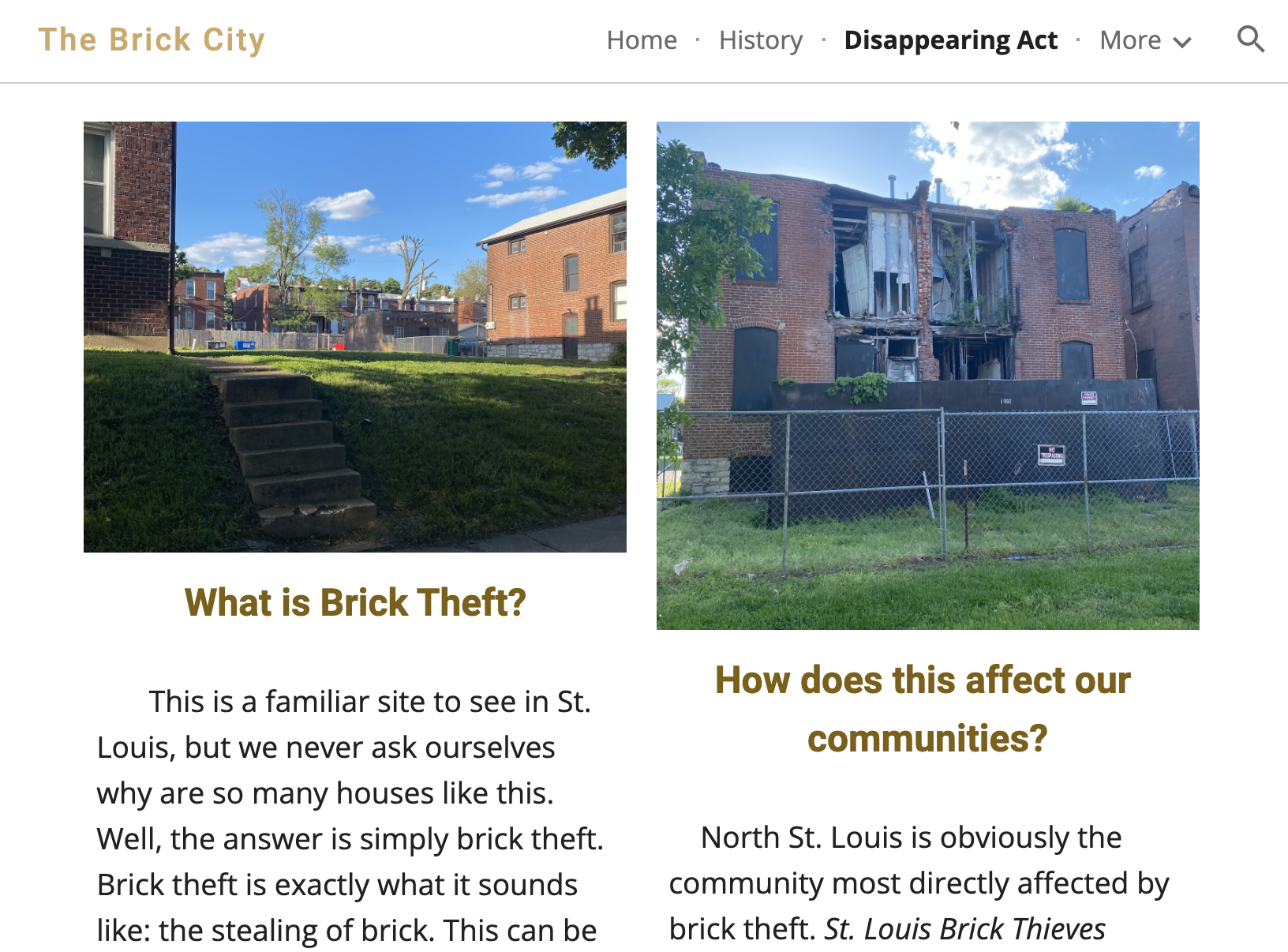

While students create their projects, I share examples from the past. We discuss choices the creators made. Since students usually create a Google Site, we discuss how the conventions of websites differ from those of academic essays. We also discuss how the mode of information—text versus image—impacts the visitor’s experience. The following page from one student’s Google Site uses images, headings, and text to convey ideas.

TakeawaysTurning an idea into a reality is both exciting and challenging. Some ideas will take students more time than they imagined; other ideas may fizzle. Make sure students know that it’s okay if their plans don’t come completely to fruition. Encourage adjustments and new pursuits. |

5. Improving

After students have completed (or almost completed) a draft of their projects, they review each other’s work in small-group workshops. The workshops function like art galleries. Each student displays a project. Then, one by one, other group members shuffle by and review the work. Reviewers write down compliments, questions, and suggestions.

TakeawaysTo prepare for peer-review workshops, make sure students understand how to give and receive feedback. Provide clear instructions and model the review process. Try this simple review process:

|

6. Presenting

During a presentation day, students host a classroom showcase. Like the peer-review workshop, the showcase functions like an exhibit hall or art gallery. I arrange the classroom desks in a large U-pattern. Half of the class act as presenters, displaying their Google Sites. The other students serve as visitors. Visitors roam the room and interact with the presenters’ creations, while the presenters stand by for questions and comments. Students then reverse roles during the second half of class.

TakeawaysLook for opportunities for students to present their projects to authentic community audiences. |

Teacher Support

Consider this support as you help students inquire about their community.

Levels

4–12

Learning Objectives

- Develop bigger and better questions about your community.

- Find, question, and interpret relevant photographs and images.

- Plan a multimedia project about a community topic.

- Engage in primary and secondary research.

- Use search terms effectively.

- Assess the credibility and accuracy of each source.

- Summarize, paragraph, and quote ethically.

- Synthesize ideas from sources to inform, argue, and/or narrate.

- Effectively combine text, visuals, and sound.

- Collaborate and share learning with peers.

Teaching Tips

- Reserve a number of weeks (3–5) for this unit.

- Integrate standards-aligned minilessons at various stages in the project.

- If some students do not find answers to their initial questions, that's okay. If their plans don't come fully to fruition, that's okay, too. Suggest they create something that offers a "behind the scenes" look into their inquiry process, including frustrations and dead ends.

- Check out additional resources for inquiry:

- Program: Inquire: A Student Handbook for 21st Century Learning

- FAQ: What Is Inquiry?

- Blog post: Using Inquiry Projects to Teach Language Arts

- Minilesson: Asking Bigger and Better Questions

- Minilesson: Creating a Rubric to Evaluate Projects