“Trust your hunches. They’re usually based on facts filed away just below the conscious level.”

— Dr. Joyce Brothers

That pit in your stomach, that flutter of your heart, that frisson down your spine . . . sometimes your body knows things before your brain does.

More than odd sensations, these signals from our bodies can actually help us and our students to think.

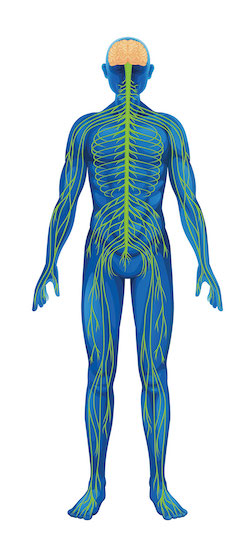

In her new book The Extended Mind, Annie Murphy Paul explores the power of bodily intuition (what psychologists call interoception). She cites numerous studies that prove that the most successful Wall Street traders, the most unflappable Marines, and the most effective students think with their bodies as well as their minds.

Why? Because much of the input from our bodies is processed subconsciously and instantaneously, meaning we often intuitively know something before we consciously do. Tapping into this intuitive sense can make us wiser and more effective.

Paul outlines four techniques that we and our students can use to strengthen this brain-body connection: bodily meditation, affect labeling, intuition journaling, and reappraising.