Though you may be unfamiliar with the inquiry process, you use it every day. For example, imagine that you need to go grocery shopping:

You start with questions: “What do we need? What do we want for dinner this week? What could I fix quickly when I get back?” |

|

| You open cabinets, check pantries, grill family members. You make a list, clip coupons, consider specials, decide how much money you can spend. |  |

| You go to the grocery store and cruise aisle to aisle. You consider prices, ounces, brand names, varieties. Items get scratched off the list. |  |

| It’s time to buy the stuff. You provide coupons, pay your money, lug the stuff home, and put it away. |  |

| That’s when you realize that you got fat-free butter (fat free butter?!) and your kids tell you they don’t like diet root beer. |  |

| You tell them that they can do the grocery shopping next time. Then you start to make dinner—and launch into the inquiry process once again. |  |

The inquiry process should be familiar because it’s the way we move from where we are to where we want to be.

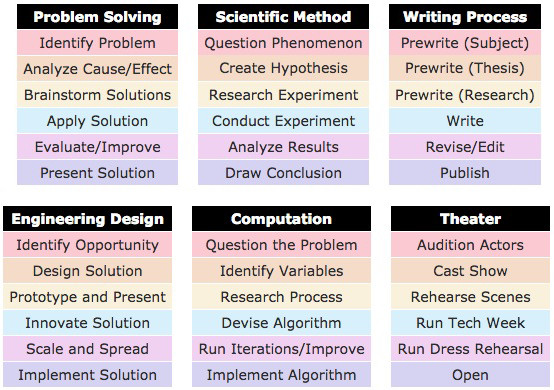

Specific Types of Inquiry

Even if you aren’t used to thinking of the inquiry process, you are probably quite familiar with other versions of it. Read through the following familiar processes, noting how each step matches up with the diagram above.

Do you see how flexible the inquiry process is? It applies to understanding superluminal neutrinos as well as to delivering jokes on stage.

Science and Theater: Strange Bedfellows?

In case you are dubious that science and theater could use the same process, consider the words of Albert Einstein: “The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking.” Science is just really good grocery-store thinking. In fact, Einstein came up with his theory of relativity when riding a local bus. Like most bus riders, he wanted the vehicle to go faster. In fact, he wondered what it would be like if the bus could travel at the speed of light.

I have my own example of everyday science. I often appear onstage at my community theater, portraying ridiculous characters. When I tell a joke and don’t get a laugh, I think, “Did I say it too fast? Did I garble it? Should I add a spit-take? Is it just the audience tonight?” In other words, I identify variables. Then I try to isolate the variables. The next time I deliver the joke, I do something different—I experiment. And over the course of a 12-show run, I use this sort of scientific process on every joke so that by the final show, I’m perhaps twice as funny as I was opening night.

And speaking of hilarious science, I’m currently plaguing the folks at CERN and Fermi Lab with my pet theory as to why neutrinos seem to be moving faster than light.

Inquiry Everywhere

So, whether students want to discover earthlike worlds around distant stars or just want to come back from the grocery store with the right kind of bacon, they need to learn the inquiry process. And if you use this process in your classroom, students will recognize it as real-world thinking.

For another take on the inquiry process, read Betty Ray’s illuminating article posted on the Edutopia Web site. She speaks about design thinking and outlines a very similar process. Make sure to read the comments below the article and notice how many different names the respondents give to this process. By whatever name they call it, all respondents agree that it’s time for the inquiry process to take center stage in the classroom.

We want to hear from you! What other processes do you use that parallel the inquiry process? How do you use inquiry in your classroom? Please enter your ideas below.