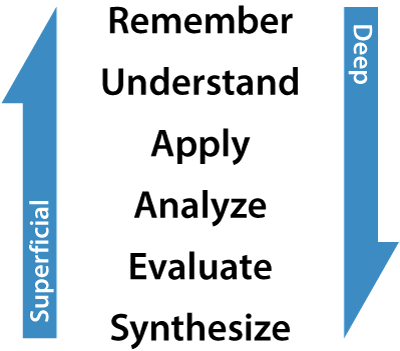

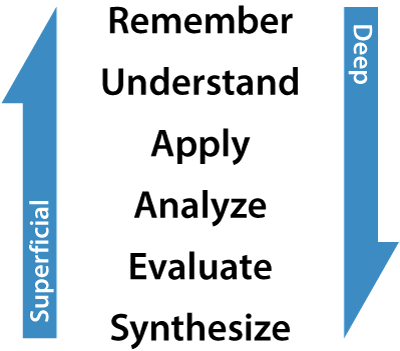

The Common Core State Standards require students to think more deeply in all classes. But what counts for deeper thinking? Bloom’s revised taxonomy lists thinking skills in order from superficial to deep:

For many years, we’ve done well teaching and testing the top half of the taxonomy. After all, multiple-choice, true-false, and fill-in-the-blank items do an excellent job of measuring what students remember, understand, and can apply. On the other hand, they don’t easily measure what students can analyze, evaluate, or synthesize. What is tested is taught, so our inability to test these skills has meant that they were not getting taught.

However, the new assessments for the Common Core test the full range of skills required. These tests combine new strategies, interactive environments, simulated research situations, and good-old essay responses in order to assess how well students can analyze, evaluate, and synthesize. Of course, now that these skills will be tested, they must be taught.

How can I teach analyzing and evaluating?

Start by teaching thinking strategies. One strategy that most educators already know is using graphic organizers to stimulate thinking: